Two years ago, as tents sprouted in city centers across the U.S., the Occupy movement demonstrated a widespread outrage with the new Gilded Age. Only in a few cities did the movement continue as a cohesive banner for progressive forces, but 2013 made it clear that urban populism has not folded with the tents. The capitals of the deeply unequal New Economy — Seattle, San Francisco, New York City, Boston and Washington, D.C. — have all seen populist stirrings this year as those left out fight back.

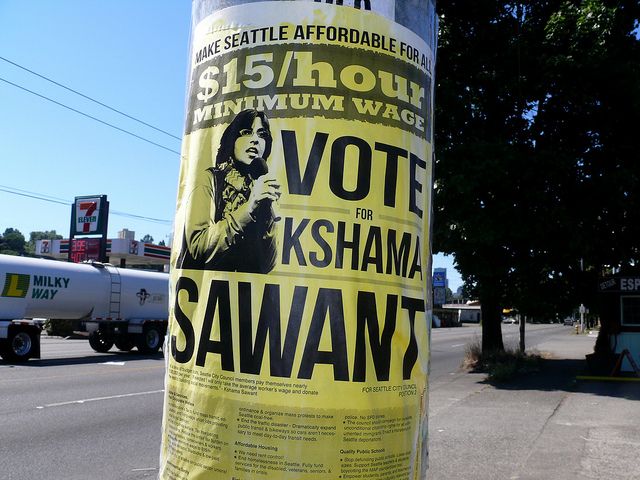

New York’s mayoral race is the most famous example. Replacing Mayor Michael Bloomberg, an Upper East Side billionaire, is Bill de Blasio, who ran an avowedly progressive campaign on a platform of higher taxes on the rich, ending racist stop-and-frisk police tactics, and protections against gentrification. In Seattle, an openly socialist candidate for city council beat a powerful Democratic incumbent by more than 1,000 votes, running on a platform of a $15 minimum wage and rent control to combat displacement. (Another socialist candidate in Minneapolis came close to victory, losing by a mere 229 votes.) In the suburb of SeaTac, Wash., voters approved a measure that would grant the aforementioned $15 minimum wage to workers at the Seattle-Tacoma airport. In San Francisco, anger at tech companies’ privatized transit for its workers — the so-called Google buses — boiled over in a series of protests. Across the Bay in Richmond, Calif., a Green Party mayor fought Wall Street in an attempt to aid city homeowners who were cheated by fraudulent financial practices.

The list goes on. In Boston, Martin Walsh of the Laborers International Union won the mayoral race despite opposition from the business community. And perhaps most poignantly, in increasingly wealth-divided Washington, D.C., the minimum wage was raised to $11.50 (by 2016) and indexed to inflation in conjunction with similar measures in suburban Maryland counties. (Another bill, vetoed by Mayor Vince Gray in September, would have required Walmart and other big box retailers to pay employees $12.50 an hour plus benefits.)

Even the persistent popularity of confirmed crack-smoking Toronto Mayor Rob Ford is evidence of a darker variation on this trend. Look at his base: Working-class and lower-income people living in the far-out, high-poverty areas of the city. These are people who have been pushed away from the downtown core as housing costs have climbed upward with the skyline, while wages have stagnated or worse.

But even the recent electoral backlashes against urban inequality don’t guarantee results, as there are structural and political limits to any municipal government’s power. Again, de Blasio serves as a good example: After campaigning on a promise to end stop-and-frisk, he chose William Bratton, the man credited with pioneering the approach, as his police commissioner. Though Bratton has said he will reform the NYPD’s use of stop-and-frisk, he has also, in no uncertain terms, endorsed the tactic as “a basic, fundamental tool of police work in the whole country.”

Furthermore, many of de Blasio’s policy promises depend on approval from the more conservative state government, including increased taxes on the wealthy (which would fund his plan for universal pre-K programs) and his vaguely worded “fight to retake control of rent rules from Albany.”

Still, developments in 2013 show that significant battles can be fought, and won, on the municipal level. Relatively dense cities with a central core and transit options are still far easier to organize than, say, the exurbs. There’s a reason occupations took place where they did, and a reason the fast food strikes sweeping the nation mostly happened in urban areas. But resistance to inequality has developed unevenly: Why have some cities seen populist uprisings while others continue to slumber?

The experience of Los Angles shows that a large, politically active immigrant population can be a powerful force for progressive change. Hispanic and Asian immigrant populations in L.A. have gained substantial political power since the 1990s, turning the city into a progressive bastion with significant implications for state-level politics. In the 2010 midterm elections, when Tea Party Republicans won victories across the country, California was a substantial outlier: Democrat Jerry Brown easily won the gubernatorial race and Barbara Boxer handily won reelection. Essential for both was the massive support they received in Los Angeles County, where more than 25 percent of the state lives.

Brown and Boxer each won well over 60 percent of the vote in L.A. County. At least one-third of those voters were Latinos, thanks in large part to a huge get-out-the-vote effort orchestrated by labor and community groups who have been organizing with immigrant workers since the mid-1990s. (In recent years Los Angeles has chocked up other progressive wins, including massive approval of a ballot initiative that raised sales taxes to fund a substantial expansion of public transit infrastructure.)

Los Angeles also shows that a powerful and innovative labor movement is important, too. This trend is evidenced in New Haven — where unions and community activists have won control of the city government — and Seattle, where labor has proven willing to endorse candidates outside the Democratic Party, while beating back concessionary employer demands. (It’s no coincidence that both candidates in this year’s mayoral race endorsed a $15-per-hour minimum wage in the city.) In Philadelphia and Detroit, where the labor movement is strongest in conservative building trades and the besieged public sector, progressive change has been much harder to win.

Which isn’t to say it can’t be won. There is deep historic precedent for urban backlashes against economic inequality. The progressive, socialist and trade union movements all had most of their strongest bases in cities. As Peter Dreier wrote in Dissent this month, “One hundred years ago, at the Socialist Party’s high point, about 1,200 party members held public office in 340 cities, including seventy nine mayors in cities such as Milwaukee, Buffalo, Minneapolis, Reading, and Schenectady.”

Bolstered by substantial immigrant populations in these areas, progressive municipal politicians implemented groundbreaking social legislation that wouldn’t be seen at the federal level until the New Deal: Anti-child labor laws, workplace safety standards and protection from police attacks on striking workers. Popular movements in the 1960s and 1970s, chiefly among African Americans, wrested control of municipal governments from white political machines and, temporarily, won expansions to the social safety net. But municipal-level policies cannot, by themselves, reverse deepening income inequality. Banking regulation, labor law reform, universal health care and the defense of voting rights — to name a few issues — must be fought at the state or national levels.

There cannot be social democracy in one city, even one as resource-rich as New York or Los Angeles. Municipal governments certainly have the power to improve the lives of their non-wealthy residents. But politicians need to feel strong popular pressure, and face real progressive electoral challenges, to ensure they join the fight at all.