Through Illegal Pipes and Shady Cartels, Water Flows Into a Slum

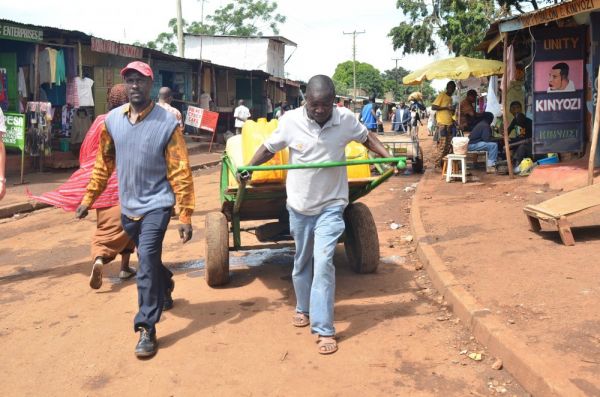

A water hauler with his cart. Photo credit: Jason Patinkin

Mike Techara wakes up at five o’clock every morning to haul a cart loaded with bright yellow jerrycans of water to dozens of families living on the edge of Kibera. He makes this trip up to five times a day, dragging a heavy load of twenty full twenty-liter jerrycans as far as a kilometer along bumpy roads to his clients. During the low-demand wet season, when people can collect rainwater for washing, he charges ten or fifteen shillings (about nine cents USD) for one can, but in the higher demand dry season, the price shoots up to twenty or thirty shillings, the highest in all of Nairobi.

On the outskirts of the city’s most famous slum, where infrastructure is weak or nonexistent, residents have no other option but to buy their water this way. Though the city is mandated to provide drinking water to all slum residents, in reality the municipal system barely reaches past the edge of informal settlements. So residents of such settlements rely on haulers like Techara and a complex system of pipes operated by illicit water cartels. The makeshift infrastructure is an example of how residents in slums must innovate to meet basic needs when the formal city falls short.

Mike Techara fills the jerrycans he’ll deliver to residents on the edge of Kibera. Photo credit: Jason Patinkin

Monica Njeri, 30, lives in a multistory apartment building, part of a slum upgrading project near Kibera, with her three children. There’s a rain catchment tank on top of her building with pipes, but she says it only runs once a week—if there’s rain. So she buys ten jerry cans a day from a cart hauler like Techara for twenty shillings each. “I use three per day for washing, and for bathing and toilet I use three or four per day because I have children,” she says. The rest of the water goes to cooking and drinking.

Surprisingly, it’s deeper inside the slums, where rents are cheaper but the narrow pathways make carts impossible to pull, where running water is easier to find. Indeed, there are so many pipes snaking above and below ground that pedestrians must take care not to trip over them as they make their way through the warrens of shacks. Thousands of colorful plastic and rubber tubes weave in and out of the compacted clay earth, diving into piles of refuse and running along open drains to bring drinking water to the nearly million Nairobians living in informal settlements like Kibera. All of these tangled “spaghetti connections,” as they’re called, are illegal.

A man fills his 20-liter jerrycan at a tap in Kibera. Photo credit: Jason Patinkin

The spaghetti connections are set up by water cartels. They hook up to the municipal supply and take water to neighborhood taps and water tanks where people pay to fill up their jerry cans. Nairobi’s Athi Water Services Board (AWSB), which oversees the city’s water policy, mandated in 2009 that public utilities provide water to all citizens in informal settlements, and the cartels play an indispensable role in achieving that goal.

“It’s not that the informal settlements don’t receive services,” says Kenneth Owucha, an AWSB economist. “They receive services through cartels, people who steal water and sell to them.” Indeed, all the drinking water used in slums is treated at the Ndakaini Dam on the Thika River some 70 kilometers from the city, before it’s piped to nearby pumping stations. It’s the cartels and their spaghetti connections that bring the water those last few blocks to the people inside the slums.

That’s convenient for Liz Oliver, 27, who fills her jerry cans from a large black water tank owned by a cartel just a few steps from her mud-and-metal Kibera home. She says the water’s flow is irregular at best. “Often it breaks,” she says, pointing at a winding plastic hose feeding into the tank. “Sometimes even for two to three days before it comes back.” She says the cartel fixes leaks with rubber bands. Just in case, she always keeps four or five full jerrycans in reserve.

A spaghetti connection feeds the tank used by Liz Oliver. Photo credit: Jason Patinkin

The cartels also charge more for water. Oliver pays five shillings for twenty liters in the wet season, two shillings more than the official fixed price, but below the delivery charge Njeri pays in her apartment. Still, in the January dry season prices can go as high as twenty shillings per jerry can for Oliver to fill up at the nearby tap, equaling that of a delivery cart.

Her biggest complaint is the quality. She points to where her pipe disappears into a pile of garbage clogging an open sewer. “You can see there’s this pipe here,” she says. “It’s passing through these dirty places.” Broken pipes don’t just leak out water, they let in waste, so by the time the cartel water reaches a tank or tap, water that was safe when it entered the slum could be contaminated. In Kibera, residents either risk disease or spend more money on charcoal or WaterGuard, a water treatment chemical, to boil or purify. Oliver, unemployed, drinks her water straight, and says she just recovered from a bout of typhoid, a water-borne sickness.

Owucha says AWSB is making inroads to replace this imperfect and redundant infrastructure, but is constrained by policy. “One of the preconditions of being connected [to our water supply] is providing a title deed,” says Owucha. “And in the case of informal settlements, they don’t have title deeds.”

Unable to hook up to individual homes, AWSB’s solution is to copy the cartel’s system of piping water to neighborhood tanks, but to do it better by building water kiosks supplied by thick metal pipes designed for carrying drinking water.

Customers at Sylvia Anyango’s licensed water kiosk. Photo credit: Jason Patinkin

Sylvia Anyango, 52, operates one such kiosk in Kibera. She lives a few minutes from the northern edge of the settlement, and owns a silver 10,000 liter tank, similar to the one where Oliver gets her water, but hooked up to a higher quality pipe and serialized water meter. On a typical afternoon, dozens of neighborhood residents line up to fill their jerry cans for four shillings each—one shilling more than the city’s set price of three. Despite the slightly higher than official price, Anyango’s kiosk still beats the cartel’s costs.

But Anyango’s is one of only a few hundred water kiosks in all of Nairobi, and the cartels affect her business, diverting water that she has to account for. “I can’t tell how much water comes in,” she says. “Sometimes people cut the lines.”

Owucha, the AWSB economist, says the city itself doesn’t know how much water the cartels take away, or even how much is used in slums. “Because of this puncturing of the system it is impossible to tell,” he says. “But on average the city loses about 40 percent of water, though that also includes technical losses.”

AWSB would like to stamp out such inefficiency, but the spaghetti connections, which dive under streets and through houses, are complex, and Owucha says there is official fear of slums. “The employees of the water company, unless accompanied by security, do not go there.” And absent a comprehensive network of water kiosks, the city is forced to rely on the spaghetti connections to fulfill that last kilometer of its mandate.

So AWSB continues its piecemeal replacement of cartels with kiosks, and will soon build fifty more water kiosks in nine Nairobi slums, including Kibera. The project would reach thousands of people, but remains a small drop in the process to extend the city’s infrastructure into slums. For the near future at least, getting a glass of water in Nairobi’s informal settlements won’t be as simple as turning on a tap.