Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberIt’s a grey and rather dismal Saturday afternoon in November, but the Horseshoe Casino in downtown Cleveland feels alive. Elegant chandeliers hang from the ceiling while a soundtrack of ’80s rock — “Danger Zone,” “Smooth Operator” — is interrupted by the electronic pings and yawps from flashing machine games. Waitresses weave through clumps of guests gathered around blackjack tables and slots, most of whom keep on their jackets and hats, as if they only meant to step inside for a moment. A gilded “High Limit” area has enough windows for those on the common gaming floors to look askance at the heavy rollers inside.

I met Joe at the bar, where he was enjoying a drink and watching college football. Joe, a pipefitter and native Clevelander, wasn’t here to gamble. A white-bearded man in an Indians hat and wearing two fleeces, one over the other, he doesn’t think much of gambling. But he’s here to accompany his wife, who likes the games but refuses to venture downtown from their suburban home without him.

It’s not hard to understand why. One out of every three Clevelanders lives in poverty, a human suffering visible in a downtown scarred by once-gracious vacant buildings. Many sidewalks built with optimistically broad widths appear untouched, especially at night. Cleveland has registered on “most dangerous city” lists with disquieting frequency. Fair or not, downtown carries a lot of the baggage.

Nevertheless, the casino was bustling with patrons on a recent chilled weekend, a hearth in center city. “They’re trying to bring people back,” Joe — who declined to give his last name — told me. “And you could sort of see how it could work.”

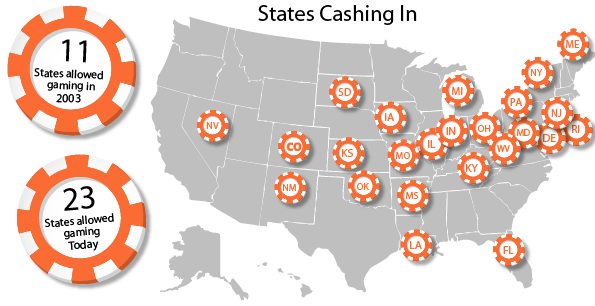

It used to be that casinos made a destination out of a rare few cities: Las Vegas, Atlantic City, Reno. That is changing as states and cities grow hungry for new sources of revenue to plug budget holes. Ten years ago, 11 states allowed commercial gaming in land-based, riverboat or racetrack casinos. Now, 24 do. (A dozen additional states host Native American casinos.)

“This wasn’t just one casino in the state sitting out in a cornfield near a highway off-ramp… but one in each of the state’s largest cities, employing local companies and workers as much as possible.”

As states approve gaming, it’s often the large and mid-size cities that hurry to make casinos feel at home. Pennsylvania, for instance, has 10 casinos, with three concentrated in the Philadelphia region; the city itself is the only locality with approval for a second facility. All three non-Indian casinos in Michigan are in Detroit, two of them practically within a baseball’s throw from each other. There’s enough activity in the Detroit casinos to make it the fourth largest casino market in the country, generating $1.4 billion in revenue.

The casino where I met Joe is Ohio’s first full-service gaming facility. Others opened in Toledo and Columbus soon thereafter, and in March another Horseshoe Casino in Cincinnati will welcome its first guests. By opening casinos in four major cities, the hope in Ohio goes beyond the sparkling lights, lavish buffets and even the potential for tax revenue: As investments that rival only stadiums in scope, these casinos are tasked with bringing life to urban economies. From foot traffic to spinoff businesses, from jobs at craps tables to construction work, more and more communities are betting on casinos to fill the void in city centers. The new entertainment option is also expected to entice people to neighborhoods they don’t otherwise visit, and could go a long way toward assuring newcomers, like Joe’s wife, that the city isn’t as frightening as they believed.

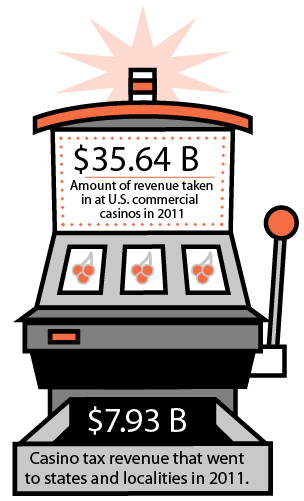

It took four failed ballot measures before the initiative that legalized gaming in Ohio passed in 2009. The constitutional amendment approved by voters details how casinos will be taxed — 33 percent of gross revenues. Comparatively, Maryland casinos will be taxed at just below 50 percent, down from 67 percent (a nationwide high) after a November ballot initiative. Casinos also pay for licenses and one-time fees.

About 12,000 people live in Downtown Cleveland. Though still a small percentage of the city’s population, the number now is larger than it was a decade ago.

For many voters, support hinged on the notion that gaming would significantly boost local economies and public services.

“We think the reason we were successful [this time] was because we had a different approach to stimulating community development,” said Jennifer Kulczycki, communications director for Rock Gaming, which, in a joint venture with Caesars Entertainment, co-owns the Cleveland and forthcoming Cincinnati casinos. “This wasn’t just one casino in the state sitting out in a cornfield near a highway off-ramp… but one in each of the state’s largest cities, employing local companies and workers as much as possible.”

In addition to their economic impact, casinos are sold as appealing additions to the urban landscape. Cincinnati’s $400 million, 23-acre casino includes a one-acre outdoor plaza in front of the main entrance intended for festivals and special events, as well as to buffer the casino from its neighbors. While the Cincinnati casino is off Interstate 71, and a little set off from the city center, Kulczycki said that “the orientation is very directed at downtown.” She sees the entryway into the new casino as an important space: It needs to be welcoming and “act as the link between the casino and the community.”

But the promise of urban casinos carries no small risk — and not just for individuals who stand to lose on the betting floor or fall prey to addictive gambling. Indeed, the actual return on investment for cities is uncertain.

Before Ohio passed its casino legislation, all of its neighboring states — Michigan, Pennsylvania, Indiana, West Virginia and Kentucky — offered casino gambling, and plenty of Ohioans traveled across the borders for them. About $1 billion was leaving the state annually as residents went elsewhere for casinos, Ohio officials estimated.

But to make that same amount of revenue, Ohio needs not only to keep those gamblers in state but also attract betting hands from out of state, experts say. The number-one factor for positive local impact is how many visitors the casino brings in from outside the region, according to a 2010 study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. If it’s local money at the poker tables, it’s usually chalked up to displaced economic activity — local gamblers would have spent their entertainment dollars locally anyway, at a pub or a theater, if the casino did not exist.

Of course, as casinos proliferate, the potential for being an out-of-town draw is a game of diminishing returns. For example, as more Mid-Atlantic states legalize gaming, including neighboring Pennsylvania, Atlantic City is hosting significantly fewer visitors in its casinos. In 2011, gross gaming revenue dropped 7 percent, and direct gaming tax revenue dropped 9.1 percent. Even as the study indicated that casinos in Pennsylvania had a positive economic impact, it isn’t clear if the benefits will offset costs, or if short-term gains will be sustained over time. In Philadelphia, for example, it’s an open question whether it was worthwhile to offer valuable waterfront property to a casino, rather than other facilities that would benefit the city.

Downtown Cleveland struggles with vacancy in many of its commercial neighborhoods. Local leaders hope the casino will bring more people downtown for shopping and recreation.

Brookings Institution Senior Fellow Alan Mallach, author of the Philadelphia Fed study, cites Atlantic City as an example of the uncertain return on casino investment. “They wanted casinos to bring gamblers in there so they could empty their pockets and then go home to Baltimore or Philadelphia. The whole model worked against spinoff investment,” he said, explaining that casinos operate by trying to keep customers indoors for their entire visit. “And after 30 years, there was remarkably little else [in Atlantic City].”

With its entrenched poverty and languishing neighborhoods, the seaside resort town proved to be a mixed bag, Mallach said. “It’s a big question if [casinos] spark much other investment in the city.”

Bryant Simon, author of Boardwalk of Dreams: Atlantic City and the Fate of Urban America, quantifies the failure with a simple fact: About 200 restaurants and five movie theaters went out of business in Atlantic City in the first decade after it became a casino destination.

“The idea that casinos are a quick fix — well, that’s the same thing gamblers think,” Simon said. “Yeah, it’d be great to have more money. But normally, people work. You can’t get something for nothing. Cities want the same thing. But casinos are not going to save them.”

The Horseshoe Casino in Cleveland opened last May in the shell of a historic department store, the long-empty Higbee Building. It is the only Ohio casino to occupy a historic downtown building, rather than a new facility built from the ground up. The grand retail anchor of a 1920s-era development called Tower City, located in downtown’s Public Square, the store is no stranger to high-profile gigs; in 1983, the film A Christmas Story was filmed in its elaborate display areas.

The casino’s co-owner is Rock Gaming, owned by Dan Gilbert, the CEO of Quicken Loans and owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team, as well as a major force in the redevelopment of the downtowns of both Cleveland and Detroit. Rock Gaming plays up the building’s place in civic lore. On its walls is artwork featuring the Cleveland skyline and local heroes: Players for the Browns, Cavaliers and Indians, as well as Superman, whose creator was from Cleveland. During the holiday season, the casino celebrated with bountiful Christmas decorations inside and out — 25,000 lights, 2,000 ornaments, a 24-foot tree — all custom-designed to honor the lush holiday displays of the Higbee’s department store, beloved by generations of Clevelanders.

The grandeur belies the casino’s uneven performance. Still in its honeymoon year, it’s not surprising that the first weeks of Ohio’s first casino saw a rush. That rush, though, ended quickly. By the end of 2012, revenue leveled off at a 20 percent drop from its first full month in June. It took in $20.4 million in adjusted gross revenue in November, or about $355,000 after winnings were paid. It was the fifth straight month of falling revenue, though in relatively small drops. The casino’s general manager, Marcus Glover, told the Cleveland Plain-Dealer that “it’s too early” to make conclusions about the casino’s performance; a year needs to pass in order to make same-season comparisons.

“The idea that casinos are a quick fix — well, that’s the same thing gamblers think.”

The numbers don’t worry Joseph Marinucci, president of the Downtown Cleveland Alliance, a membership organization of business owners, residents and stakeholders. The big picture, he said in a recent interview, is that the casino is bringing life back downtown. “From the get-go, our property owners felt [the casino] was a great addition to what we’re trying to do downtown,” Marinucci said. He lauded the casino’s choice to renovate a historic building, and praised its partnerships and rewards programs, which send patrons to 15 local restaurants and three hotels outside the casino gates.

“They’re putting people on the streets, animating the sidewalk,” Marinucci said. “People are seeing other people and feeling safe downtown. And that block was a significantly under-populated block.”

But is that enough? In the upcoming year, Ohio municipalities will lose close to $1 billion in unrelated state cuts, according to a study by Zach Schiller, research director at Policy Matters Ohio, a nonpartisan public policy organization. Revenue from the casino tax is expected to provide just $227 million a year to the four counties and four cities that host the casinos. As the report puts it:

Even for these governments, the estimated amount they are to receive in casino gaming taxes on average will be only half of the revenue they are expected to lose because of the current state budget. Nor will the additional aid to school districts make up more than a fraction of state cutbacks to education funding.

That means that Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus and Toledo are receiving less in gaming taxes than they will lose in cuts to state aid in 2013. “Estate tax elimination alone is likely to offset Cincinnati’s casino tax gains,” the report states. At the same time, the casinos require the city to put up an ongoing investment in increased public services. The report predicts that the Cleveland casino will tally $2 million for public safety outside its walls this year, and “nearly $600,000 for public services, such as keeping the area clean,” all at city expense. The operator of the Toledo casino gave a neighboring suburb (not, curiously, Toledo itself) $200,000 to help stem the burden of expense for additional police and fire services required for increased traffic. Even so, there are gains: Without yet seeing a full year of operation in Ohio, the state put an additional $15 million into education, all funded by casino revenue.

But, Schiller said, “I wouldn’t want Ohioans to think that casinos are taking care of our schools and cities.” He added that the successful ballot initiative didn’t just change policy — it changed the state constitution. Rates cannot easily be changed if the public decides the tax should be increased. The casinos themselves wrote the amendment, he said.

Marinucci, for his part, sees the casino as simply one part of Cleveland’s entertainment network. He said it doesn’t take away from downtown’s potential as a residential community, either. While downtown wasn’t historically a large population center, he said, it’s on an upward slope: About 12,000 residents now, with occupancy at 97 percent. DCA’s goal is to see at least 20,000 residents by 2015, which Marinucci said is more likely if downtown is a “24/7 environment.” But he added that “yes, there’s a cost-benefit analysis to be done” on the casino’s impact, and no formal economic development evaluation has been completed because DCA is waiting for the casino to stabilize. So, reports of nearby restaurants keeping longer hours, for example, can’t yet be strictly attributed to the casino. Even if it’s true, it could be another iteration of Mallach’s displacement — perhaps restaurants stay open later to cater to casino patrons, but they’re opening later too, and ultimately keeping the same number of hours.

In its first year, Horseshoe hired 1,600 permanent workers at its Cleveland casino.

So, when it comes to new casinos, is there anything that cities can count on?

Where the Ohio casinos may be limited in terms of economic development, they do offer a useful model for how to do building projects in ways that have the greatest benefit for the local community. They also set a high standard for ensuring that people historically excluded from downtown jobs, whether in construction or in permanent positions, land them.

Job opportunities are significant: All four casinos are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they accepted unionization of workers last summer. This comes in the context of immense struggle for working people in the host cities. Toledo, for example, had an unemployment rate of more than 14 percent in the last three years. The casinos also hired local companies for their construction, making the economic impact of their arrival a strong one.

The Cleveland casino hired 1,600 permanent workers and the one in Cincinnati plans to hire 1,700. Positions range from bartenders and servers to accounting and finance. In December, Horseshoe Cincinnati opened a 12-week, 240-hour “table games serving academy” in a finished warehouse on the casino complex, training 750 people in how to host games like blackjack, craps, poker and roulette. In a significant lapse, the training is unpaid. (In a testimony to the demand for jobs, 5,600 people applied for the 750 training positions.) At the end of the training — for those who complete it successfully — the casino promises a job that pays between $35,000 and $45,000 a year. The median household income in Cincinnati in 2009 was $32,754.

Jeremy Miller knows northern Ohio. He grew up in a tiny village in Sandusky County. He’s fished Lake Erie. He graduated from college in Bowling Green and, since 2006, has sold insurance in Cuyahoga County. Miller, 31, lives in Fairview Park, about 10 miles outside Cleveland. In the months since the Horseshoe opened, he’s made the trip a number of times to play poker and blackjack. The Cleveland casino, he said, has “better poker tables than pretty much anywhere, even Vegas.” Miller enjoys playing at the casino, and he’s glad to know that some of the casino’s money is going to support Ohio schools. But he’s acutely aware that the casino could exacerbate problems facing the region.

“I know when I go there how much I can spend, how much I can afford to lose, and I know how to stop,” Miller said. “But some others might have gambling problems, spending too much and causing them and their families problems. Which probably makes the economy worse.”

Before the successful ballot initiative, Kulczycki told me, Rock Gaming polled Ohioans to ask, fundamentally, if they believed gaming belongs in their state. A resounding yes came back. Lottery and racing had already become part of the ordinary fabric of Ohio, and casinos didn’t seem qualitatively different — so long as revenue stayed local. But the ballot referendum didn’t answer all the questions and concerns Ohioans had about casinos, and Horseshoe Cleveland has presented the city with tough questions. One recent scuffle between Clevelanders and the casino’s owners involved preservation — just the thing Horseshoe had championed when it opened in the Higbee Building. In 2011, Cleveland’s historic Columbia Building, built in 1908, was torn down for a 1,200-space parking garage to serve casino patrons. “One thing unique to gaming customers is the requirement for proximate parking,” Kulczycki said.

The casino promises a job that pays between $35,000 and $45,000 a year. The median household income in Cincinnati in 2009 was $32,754.

The looming demolition inspired protests from a loud group of Clevelanders upset that the casino opted to sacrifice the early 20th century treasure for a new garage when the city has a glut of surface lots that might have been built on. Young Clevelanders challenged the move with what is called an art attack — a chalk-in to draw attention to the demolition that, they said, with its fences and clutter, made it difficult for nearby small businesses to operate. In bright pastels, they drew and signed their names to the street. “Dan Gilbert hates good architecture,” read one bit of chalk graffiti. “A city is only as good as its history,” read another. The tactic did not save the building. By now, the garage is built, busy and charging visitors high rates. A recent 80-minute visit cost $35.

Plans for expansion include a glass-enclosed 170-foot skywalk connecting the garage with the second floor of the casino. Crossing diagonally over two large streets, the skywalk provides a way into the casino that doesn’t involve ever stepping foot on public Cleveland ground. This has become another local battle.

City Councilman Joe Cimperman, a Democrat whose district includes downtown, is among those supporting the skywalk, while councilmen Matt Zone and Zack Reed, Democrats for the west and southeast sides, oppose it, as does the Ohio Historical Preservation Office. These opponents worry that the skywalk will irreparably harm the architecturally significant Higbee Building, create an intrusion on the sweeping vistas that were part of the original vision for the neighborhood, and lock out other downtown businesses from experiencing benefits from the casino’s downtown location by limiting neighborhood foot traffic.

“The casino said they want to be part of the urban fabric, but they always say that when they’re trying to build something,” said Ned Hill, dean of Cleveland State University’s College of Urban Affairs. Speaking more generally, Simon, the Boardwalk of Dreams author, put it this way: “Casinos are about keeping people in casinos.”

Kulczycki resisted that characterization, saying that the urban casino model is “important as a compliment to the city, not drawing people away but really trying to encourage connectivity with the downtown.” The skywalk is just another piece of infrastructure needed for the casino’s success, especially during the cold, wet winter months. The construction, she and other supporters say, will create local jobs.

The Horseshoe Casino is one of the largest private investments to be made in Cleveland in decades.

In the end, casinos have conflicting business interests: If a neighborhood is perceived as unsafe, it reduces the number of potential patrons. So the casino has an interest in community development outside its walls. On the other hand, supporting development that will eventually produce competition for downtown entertainment dollars counters the casino’s basic purpose. It is not, after all, a non-profit, nor a public-interest entity.

As cities like Cleveland and Cincinnati look to integrate gaming into their downtown culture, traditional casino destinations, like Atlantic City, are working hard to expand beyond the industry. The Casino Reinvestment Development Authority in New Jersey collects 1.25 percent of gross gaming revenue for redevelopment use. (New Jersey casinos are taxed at a rate of 8 or 9 percent.) While this money applied statewide for years, Gov. Chris Christie and the state legislature are, for a five-year window, keeping it in Atlantic City. A recent marketing campaign funded by non-profit partner of the CRDA — funded in turn by the casinos through an act of the state legislature — tried to rebrand the city as a tourist destination with offerings beyond gaming. It mentioned nothing about casinos, instead promoting beaches, golf, clubs, restaurants, and boating and fishing. Another $48 million in CRDA spending went toward improving infrastructure on the town’s south inlet and bettering access to scenic spots. Other recent projects have included a public parade and a program for art installations on vacant lots.

That doesn’t surprise Hill, of Cleveland State University. “You don’t build cities on the backs of drunks,” he said.

The formula for rejuvenating downtowns, he said, is the same as ever: Secure streets, walkable neighborhoods, green space and employment opportunities.

“You can’t cater to short-term visitors and short-term guests,” Hill elaborated. “Visitors are of course part of the texture of the city, but the people who make this their home need to come first.”

“The success of downtown depends on if there’s a true mix,” he said.

More than a few new cafes, or casinos, what Ohio cities need is a whole set of different policies, said Schiller of Policy Matters. He’d like to see “more intelligent land use policies so economic activity isn’t drained away” — an important point for Cleveland, as the population in its metro region is growing even as vacancy persists downtown. “It’s very disturbing to have the urban sprawl we have,” Schiller said. “It’s far gone. [Changing land use policy now] is like closing the barn after the horse is gone.”

With that in mind, the fact that Horseshoe didn’t play by the rules of sprawl is significant. Even critics of the casino such as Amy Hanauer, Policy Matters’ executive director, said she’s “pleased to see a little more people on the street, a little more vibrancy.”

Back at the bar in the Horseshoe Cleveland, Joe mapped out for me how the Higbee’s department store once lived in this space. Where we sat, he thought, had been women’s clothing. There, he pointed, had been perfumes and maybe jewelry. Then, as now, Clevelanders strolled the floor, pausing where something bright and beautiful caught their eye. Then, as now, they came with friends and family members, as much for entertainment as anything else. The difference today is whether Clevelanders will have anything tangible to take back home.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in Elle Magazine, the New York Times, Politico, the Columbia Journalism Review, Next City and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book. She has been a Fulbright fellow in Nairobi, Kenya and a Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books in 2018.

Follow Anna .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Frank Lanza is a freelancer photographer and digital photography teacher based in Cleveland, Ohio. A lover of live music, he has captured many talented musicians on film, including Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen, The Flaming Lips, George Clinton, Lady GaGa, Passion Pit, members of the Grateful Dead, and more. Other than music and photography, his passions include a canine companion Dupree.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine