Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberMike Ray saw the flashing lights of work trucks parked on the road not far from his house, but he didn’t think much of it that snowy day in early February. The Youngstown city councilmember lives near V&M Star, a steel mill that’s been expanding recently, making pipes for the booming hydraulic fracturing industry. The trucks, he figured, must be related to the construction.

The mill is a rare bright spot in this Ohio city where heavy industry paid the bills for generations but collapsed in the 1970s, leaving behind a town starved of jobs and fading fast. Youngstown’s population has declined 60 percent since 1950. Its neighborhoods are populated by ghostly abandoned homes, its shopping districts shuttered for business, its violent crime rate stubbornly high.

Only several days later did Ray realize what the trucks had actually been doing: Cleaning up the residue from what might amount to hundreds of thousands of gallons of illegally dumped wastewater derived from the process of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

State officials said that the waste, containing unknown toxins, had been discharged intentionally into a storm sewer on Youngstown’s Salt Springs Road. The sewer drains into a tributary of the Mahoning River, a waterway in the Ohio River watershed that is already much insulted by industrial waste pumped into it over the years.

The alleged culprit? A company called Hard Rock Excavating, with headquarters on Salt Springs Road. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) charged that Ben Lupo, CEO of D&L Energy, the company that owns Hard Rock, had ordered the discharge of “brine residue material.” D&L itself had already racked up at least 120 violations at 32 drilling sites in Ohio, according to the Youngstown Vindicator, and the company’s permits to operate were permanently revoked in the days after the dumping. The United States Attorney has charged Lupo with one count of violating the U.S. Clean Water Act.

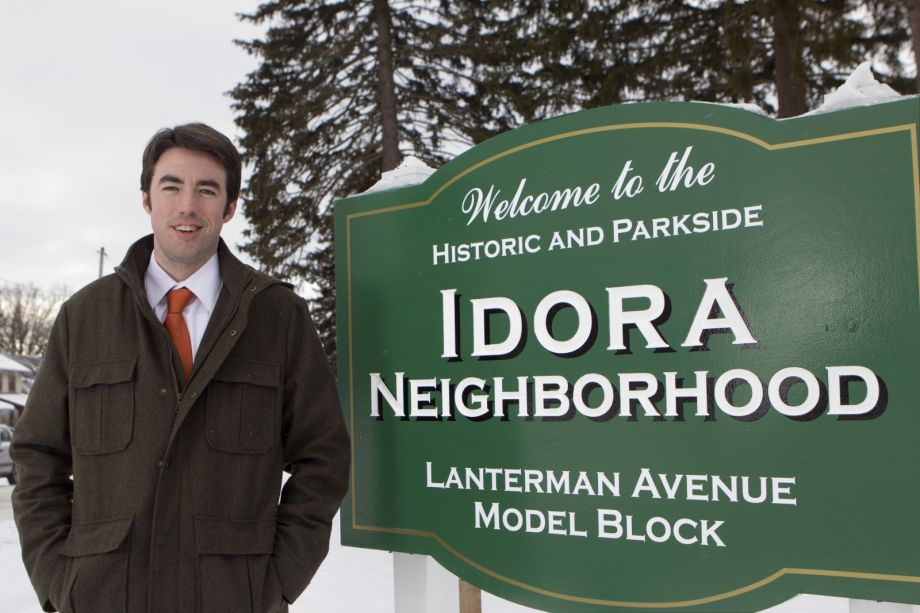

Ray, 36, wears a bowtie and glasses with a nerdy panache. A son of Youngstown’s West Side with an ingrained respect for the city’s gritty past, he went to Youngstown State University, even serving as the school’s penguin mascot, and knows all about his hometown’s old ways. But he is also a member of a generation that has seen the damaging effects of pollution and corruption firsthand and doesn’t want to put up with it any longer. “They dump stuff in the river, we should go after them,” he said. “This raises the attention for tighter regulation. This happened right under our noses. What they were doing is hiding in plain sight.”

The incident was just the latest twist in the story of Youngstown’s complicated relationship with the nation’s fracking boom. For many city residents, it took an earthquake to get them to pay attention to the burgeoning local industry.

Youngstown City Councilmember Mike Ray fears the environmental damage a fracking boom could leave in its wake.

The quakes started small, around 2.0 on the Richter scale, in March 2011. But they were frequent and unusual enough to attract media attention; the area had never before experienced such seismic activity. Observers noted their proximity to an injection well that had been used as a burial ground for the millions of gallons of water, sand and chemicals left over from the hydrofracking process.

By Christmas Eve of 2011, when a 2.7 quake hit — the tenth since March — the level of concern had risen significantly. D&L, the same company responsible for the illegal dumping, halted injection on December 30. Less than 24 hours later, the city experienced a 4.0 quake. It jolted Youngstown Mayor Charles Sammarone in his home, not far from the drilling site.

“There was a loud noise,” said Sammarone, a voluble white-haired man who has worked in city government for 30 years. “I thought someone pulled in my drive and hit the garage door. When the noise stopped, the house started shaking. I thought, ‘we better go outside.’”

The state put a temporary moratorium on injection wells after the New Year’s Eve quake, and subsequently determined that the D&L well had, in fact, been the source of the seismic activity. Ohio Gov. John Kasich signed an executive order tightening regulations on injection wells, and while the state has now resumed permitting the process, a seven-mile area around the D&L well remains off limits.

The limitation is one of few imposed on the industry’s growth. Boosters say that’s a good thing, especially for Youngstown.

To these advocates, the nascent boom, injection wells and all, is the weakened city’s only hope for economic salvation. Theirs, however, is not a view shared by everyone. To others, fracking is a powerful threat to the city’s very existence, a threat that has already proven its ability to disrupt the area’s ecosystem.

In an interview this fall, Sammarone shrugged off the concerns as a matter of politics. Though he said the industry must be regulated to prevent future earthquakes and other environmental violations, the mayor also said that fracking presents an economic opportunity the city can’t afford to ignore, and that the opposition represents a minority of public opinion.

Youngstown Mayor Charles Sammarone turned to fracking as a source of revenue because he couldn’t figure out another way to pay for blight cleanup in the shrinking city.

“There’s always somebody that’s against something,” he said.

Last fall, the conundrum became inescapable when the Youngstown City Council voted 5-2 to support opening up 180 acres of city-owned land for fracking. The idea was that fracking revenue could finance the demolition of some of the thousands of empty homes that blot city streets. It was a dismal calculus: The city would pay to tear down homes built during the last industrial bonanza, which left behind polluted rivers and soil, with money from a 21st-century fossil fuel boom that has a similar potential for environmental harm. By authorizing officials to seek bids on mineral rights, the mayor and the council forced a conversation that was just as much about Youngstown’s future as it was its past.

Ray was one of the two dissenters on the council, saying he wanted the legislative body to play a larger role in the process. He thought the council should review all requests for proposals and have an opportunity to influence the conditions required for drilling. The idea didn’t get the support it needed to be written into the policy. Despite the council vote, no proposals have yet gone out to bid, although the possibility remains on the table.

Youngstown, which has a long and not-always-proud history of embodying American socioeconomic trends, finds itself at the intersection of two national conundrums: Urban decline, meet fracking.

The fossil fuel industry is not a new thing in Northeast Ohio. Local coal powered the steel mills, and people have been drilling for oil in the Mahoning Valley, where Youngstown was founded in 1797, since the 1860s. Indeed, since shortly after its founding in 1802, this was a city built by the grimy work of grappling with the earth’s raw material: First coal, then iron, then steel. It was an urban crucible where the great industrial narrative of the 19th and 20th centuries played out from beginning to end.

Beginning at the dawn of the last century, it was steel that brought countless jobs and giddy prosperity to Youngstown, which called itself “The City of Homes” and boasted the fifth-highest homeownership rate in the United States by 1931. Youngstown back then had its own amusement park, two department stores, several movie theaters and dozens of restaurants. The industry spawned streets lined with the kind of sensible, roomy houses that solid working-class citizens were glad to own, and fancier places, too, for the management class. Many of these houses now stand vacant, targets for arsonists and havens for drug users. They are houses the city is desperate to demolish.

The change began to take shape in the 1960s, as the city’s mills started losing ground. By 1977, when the Youngstown Sheet and Tube mill shut its doors and threw 5,000 people out of work on a day known as Black Monday, Youngstown was already tumbling faster and faster into economic irrelevance. It has gone on to lose between 14 and 18 percent of its population in every decade since. Some 168,000 people lived in Youngstown in 1950. Only 67,000 did in 2010.

But when the idea occurred it was tough to dismiss: Why not sell an energy company the rights to pursue fracking underneath Youngstown’s city-owned land, in exchange for the money to bulldoze the derelict structures above ground?

The collapse of the steel industry was the most bruising blow in a punishing series of setbacks that included mob wars, corrupt businessmen, race riots and politicians on the take. The mill shutdowns brought the city to its knees. Today, Youngstown has the highest concentration of poverty of any city in the nation, a housing vacancy rate 20 times the national average and one of the highest murder rates per capita for a city its size, or any size.

The decline made the city a leader of sorts, in falling behind. About eight years ago, then-mayor Jay Williams began to implement a comprehensive plan called Youngstown 2010 that he, a former community organizer, would use to create a new frame for the city’s future. Among other policy recommendations, the plan called for accepting Youngstown’s smaller size as permanent, moving aggressively to demolish decrepit homes and encouraging residents to band together in the most viable neighborhoods. The demolition effort, the thinking went, would bolster falling property values, reduce crime and improve the quality of life for those who remained. It was one of the first articulated calls for urban shrinkage, an idea that in the years since has been proposed most famously in New Orleans and Detroit.

Williams was hailed by Governing magazine as one of its 2009 public officials of the year for his vision. “We always have to make sure we remind people,” he told the magazine, “that the transformation into a smaller community doesn’t mean we’re going to be an inferior community.” He went on to join the Obama administration as its “automobile czar” in 2011 and now serves as deputy director of the White House’s Office of Intergovernmental Affairs.

The year 2010 has come and gone, and some 5,000 houses still stand abandoned. The vision remains in place, but implementing it has been a struggle. In an effort to save money, Youngstown hasn’t employed a city planner since the last one resigned in 2009 (although they may be hiring again soon), resulting in a lack of coordination in the demolition process. Meanwhile, the city’s residents keep leaving. Tax revenues keep falling. And it’s become clear that there isn’t enough money to tear Youngstown down as fast as it’s falling apart.

Sammarone has never been a big oil and gas guy. He’s never worked in the industry or thought all that much about it. But when the idea occurred it was tough to dismiss: Why not sell an energy company the rights to pursue fracking underneath Youngstown’s city-owned land, in exchange for the money to bulldoze the derelict structures above ground?

“The biggest complaint I get is, ‘Clean up my neighborhood,’ and the biggest issue is vacant homes that need to be torn down,” Sammarone said. “We noticed other cities around us lease their mineral rights. So, we said it’s something we should look at.”

There are some 5,000 abandoned homes in Youngstown, creating a housing vacancy rate that is 20 times the national average.

Part of Sammarone’s rationale for turning to fracking as a source of revenue for the city is the seeming inevitability of the industry’s intrusion. The state regulates the oil and gas industry, not individual municipalities. Without a change in law, Youngstown can’t prevent its citizens from leasing private land for fracking. If it’s going to happen anyway, Sammarone said, why shouldn’t the city get in on the action?

That attitude isn’t shared by all of Youngstown’s neighbors, and several Ohio cities are pushing against the state with efforts to ban fracking. In August, Cincinnati became the first to ban fracking wastewater from being pumped into injection wells because of a potential risk to the city’s drinking water. At a press conference marking the passing of the ordinance, the councilmember who introduced it, Laure Quinlivan, cited a report from the investigative reporting outfit ProPublica that found one well integrity violation — a red flag for leaks or contamination — filed for every six wastewater injection wells active between 2007 and 2010.

Outside of Ohio, several municipalities, including Fort Collins and Longmont in Colorado, have passed moratoriums to prohibit fracking within city limits, even as the areas around them are being opened up for drilling. Other local governments are closely watching as Longmont faces draining lawsuits from energy companies and the state of Colorado, on the basis that its moratorium illegally restricts private property rights and usurps regulatory authority that belongs at the state level.

As in Colorado, it is essentially impossible to get away from fracking in Ohio. The state’s map is peppered with drill sites and nearly 200 wastewater injection wells. And while it looks like Youngstown won’t immediately pursue the mineral rights question, this year’s budget is only getting bailed out because of another fracking-related windfall.

That would be the tax and land lease revenue derived from V&M Star, the first new steel mill in town in 30 years. The $1.1 billion facility, owned by the French company Vallourec, is bringing hundreds of jobs back to the site of the former Brier Hill Works on the Mahoning River banks. The money V&M paid to the city last year, Sammarone said, can go toward demolition in 2013, buying the city a little more time on the fracking question.

“We didn’t lease anything yet,” Sammarone said. “But the option’s there as we move forward.” He added, “V&M has been our savior.”

And what does V&M Star manufacture at that shiny new mill? Steel piping used by the hydraulic fracturing industry.

Everywhere you go in the Mahoning Valley, you’ll see signs of the hope that the shale oil boom will pull the region out of its decades-long decline. A local newspaper, The Vindicator, known as the Vindy, has a whole online section devoted to fracking, “Shale Sheet.” The Business Daily, a regional publication, has a regular feature, “Drilling Down,” that catalogues every one of the dozens of drilling permits issued in the area. In the breakfast room of a Holiday Inn Express just off the Interstate, business travelers can peruse a biweekly tabloid called Shale Play over their morning coffee.

The energy companies have ridden the fracking boom over from neighboring Pennsylvania. It’s a path determined by geology. Under Northeast Ohio, the natural gas–rich Marcellus shale formation that undergirds New York and Pennsylvania gives way to another potentially lucrative deposit called the Utica shale.

Energy companies pay people for the rights to drill for natural gas thousands of feet below the surface of their land. If they find what they’re looking for, property owners can get royalties on top of the leasing rights. It looks like easy money.

And the environmental concerns were easy to wave off, at first. For generations, no one complained much about the conventional wells that dotted the area, or the industrial waste that ran off from the steel mills, turning the Mahoning River into a waterway so toxic that the Environmental Protection Agency long ago issued a “contact ban” for the section that flows through and downstream of Youngstown — advising against swimming, fishing or wading there.

“When the noise stopped, the house started shaking. I thought, ‘we better go outside.’”

But these are different, more educated times, and fracking is another story. While the industry maintains that fracking can be done safely and governmental regulators agree, scientists continue to raise serious questions. A study just released by two professors at Cornell University, based on interviews with animal owners in six states, found “several possible links between gas drilling and negative health.” The researchers, Robert Oswald and Michelle Bamberger, warned that lack of oversight and data could be exposing people and animals to life-threatening risks.

“The close proximity of these operations to small communities has created a variety of potential hazards to humans, companion animals, livestock and wildlife,” Oswald and Bamberger wrote.

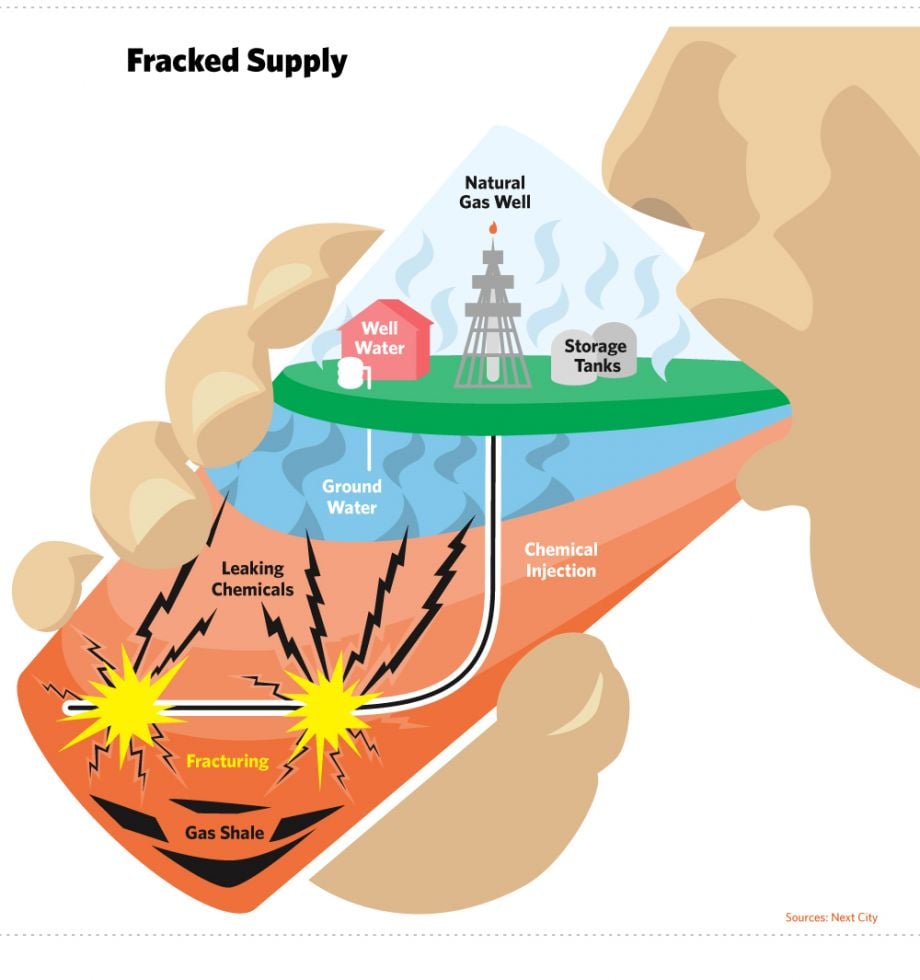

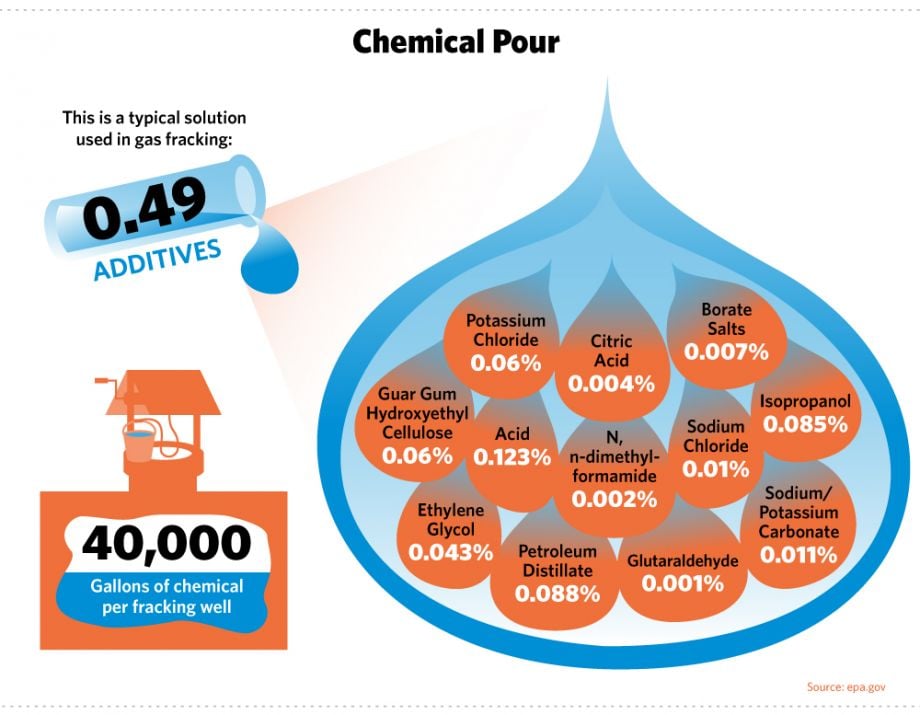

One fact no one denies is that fracking takes a lot of water. The hydraulic fracturing process works this way: Drillers pump a mixture of chemicals, sand and water — sometimes millions of gallons per well — into boreholes that extend thousands of feet beneath the earth. The pressure from the fluid cracks the rock, releasing a flow of natural gas, which is then recovered at the surface. The water, or brine, also returns to the surface. Then you have to figure out what to do with it.

That’s where injection wells come in. Because while some of the brine is reused or treated and then released into groundwater or spread on roads — in itself an extremely controversial solution — another popular disposal method is to pump it back deep underground into what are called injection wells.

For Youngstown, the rise of fracking represents the return of an economy based on extracting natural resources. Coal mines, steel mills and the infrastructure needed to power them have shaped the region’s environment for generations.

Howard Markert met me to talk about the wells at the Golden Dawn, an old-school Italian-American haunt with a gorgeous neon sign over the bar, where a couple of lone men sat and drank beer from bottles as they watched a ballgame on TV. In the red vinyl booths, a few families feasted on big plates of pasta and pizza.

Markert, a member of FrackFree Mahoning Valley and a former Green Party candidate for Mahoning County commissioner, moved to Youngstown from the San Francisco Bay Area in 2009. Now he owns several rental properties in the small city and feels committed to its future. The earthquakes were a wakeup call to him.

“What was different about these was that they were very sharp and very sudden,” he said. His immediate concern was about fire. “My properties are less than a mile from the epicenter. Every single house here has a gas hot water heater that was not secured.” He has since bolted down the heaters in his properties.

The earthquakes served to galvanize larger public awareness about the potential dangers of fracking, said Markert, who has been active in Occupy Youngstown as well. “It really woke people up to what was going on,” he said. In the months after the quakes, Markert participated in several rallies, both in Youngstown and at the state capital in Columbus, designed to bring attention to the potential dangers of fracking on city land — particularly Mill Creek Park, a 2,600-acre oasis partly designed by landscape architect Charles Eliot, an apprentice of Frederick Law Olmsted.

Mill Creek Park is one of Youngstown’s gems, but Markert and his fellow activists worry that it is at risk. There are several conventional oil wells already on the park grounds, and while local politicians have insisted they want to protect Mill Creek, Markert doesn’t trust them. “We’re trying to get as much information to local politicians as we can, saying we don’t want this,” Markert said. “Then they do things like announce that they want to sell leasing rights to pay for demolishing houses.”

The biggest success claimed so far by Markert and other activists has been a petition drive to get an anti-fracking measure on the ballot in Youngstown. The “Community Bill of Rights” measure affirms that “citizens have the right to drink clean water, breathe clean air and live on unpolluted land.” The deadline for submitting signatures came on February 6, the day after news of the wastewater dump hit the local media. Organizers needed 2,836 signatures to get the measure before voters in the May primary. They submitted 3,792. If voters approve the measure on the May 7 ballot, it would mean that Youngstown had declared drilling for oil and gas illegal within city limits, even though the city’s law director has said that the charter amendment proposal is “unenforceable” because the city doesn’t have jurisdiction over drilling.

In the cramped back seat of Ian Beniston’s beat-up two-door car are some of the tools he needs to do his job.

Hard hat, check. Bolt cutters, check. Sledgehammer, check. Demolition permit, check.

Beniston, a 30-year-old Youngstown native, isn’t really a demolition worker. He’s a certified planner and the deputy director of the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation (YNDC), a non-profit organization devoted to building up the devastated neighborhoods of this hollowed-out city. As he drives around, it seems he knows the story of every blank-eyed home we pass. Where I see empty lots, he sees the houses that used to stand there.

The people of Youngstown some years ago came to a critical realization: You’re going to have to tear down a lot of the city if you want a chance at saving any of it. Beniston and his colleagues are doing that work as fast as they can, demolishing what’s rotten, protecting what’s sound and helping people move into the homes that can be refurbished.

“We’re still in basic neighborhood rehabilitation,” Beniston said. “We’re using a targeted approach, working in a handful of neighborhoods.” Problem is, Beniston told me, they can’t work fast enough, even with a sledgehammer always at the ready.

Ian Beniston helps runs a local community development non-profit. He wonders if the economic benefits of fracking will flow back into the city’s hardest-hit neighborhoods.

Beniston and his group are doing their demolition work carefully and with an eye to the future. When they tear something down, they take pains to clear the lot completely, seed it with grass and put up a split-rail fence to let people know that this is a place that someone cares about. They target both demolition and rehab efforts carefully, assessing the housing stock and human resources block by block, house by house, so that no effort is wasted and benefits are concentrated. It’s the kind of deliberate approach that the city has not been able to afford on the mass scale envisioned by the Youngstown 2010 plan. Municipal demolition efforts are less concerted and more scattershot.

Because of Beniston’s long experience on the streets of Youngstown, he sees the appeal of fracking revenue as much as anyone. But he is cautious, too. “I don’t know if we’ve figured out if there’s a benefit or not,” Beniston said. “We don’t want to sell out our long-term future. We just have to do it in a mindful way.” He also questions the economic benefit of places like V&M to the impoverished, undereducated residents of Youngstown’s toughest areas.

“The other question related to fracking, is how much are the people in the neighborhoods getting those jobs?” Beniston asked. “The job training programs we have in town are only just getting them basic-job ready. The steel mill is hiring people with bachelor’s degrees. They could probably demand people with master’s degrees.”

“My whole thing is, where’s the balance between economics and environment — and can they be in balance?”

Both Beniston and Mike Ray, the councilmember, are confronted every day with the painful economic grind that still prevails in Youngstown. To natives who stuck it out when so many chose to cut and run, who have been waiting so long for something to replace the security of the steel mills, the shale boom can seem like sweet deliverance. Ray said that when he talks to his constituents, the yearning comes through loud and clear.

“I’ve had folks right out front on the corner grab me and say, ‘Mikey, you know what, when the mills were running and I was a kid, we were all dirty and the city had money and everybody was happy. What are you doing?’” Ray said.

“I understand the economic realities,” he continued. “By all means, you have the obligation to the city from both sides. You have the safety of the residents, but you also have to look out for the financial viability of the city. My whole thing is, where’s the balance between economics and environment — and can they be in balance?”

There are signs that a different Youngstown is emerging, if only slowly, from the ashes of its industrial past. This Youngstown isn’t about mineral rights and steel and the money that comes from dirty industry. It’s about education and information, high-tech innovation and reclaiming the city’s downtown, with its majestic limestone high-rises.

On Federal Street, the main drag downtown, the Youngstown Business Incubator (YBI) has been successfully hatching tech start-ups since the 1990s. Housed in a slick, loft-like space, YBI’s businesses employ the type of young, highly educated professionals that you would find in Silicon Valley or downtown Manhattan. The incubator’s executive director, Jim Cossler, said he has built a network of thousands of advisers for these businesses by tapping into what he calls “the Youngstown diaspora” — people who have left Youngstown for the world beyond, but who still have a deep affection for their hometown.

Downtown Youngstown has seen a resurgence in recent years, thanks to an influx of start-ups and a federal research institution dedicated to modernizing manufacturing using technology.

Last year, YBI landed its biggest fish yet: A $70 million public-private contract to house the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute (NAMII), a facility for the research and development of modern manufacturing techniques. It was NAMII that earned Youngstown a name-check from President Obama in his recent State of the Union address, when he referred to it as “a state-of-the art lab where new workers are mastering the 3D printing that has the potential to revolutionize the way we make almost everything.” This type of “clean” industry, Obama implied, holds the key to the future of American manufacturing.

Just down the block from NAMII, new retail and restaurant businesses are opening up, catering to an upscale clientele. Some of the historic buildings are being developed as condos. The city has restored the street grid connecting Youngstown State University, just up the hill, so students can walk back and forth more easily. A new community college offers the kind of education that can prepare the city’s residents for cleaner, more modern jobs. A performing arts center is pulling in eager audiences.

But YBI, NAMII and the service businesses downtown can provide only a fraction of the jobs that the fracking industry promises. And most of these high-tech jobs go to people recruited from out of state, the majority of whom, according to Cossler, don’t end up living in — or paying property taxes to — the city of Youngstown.

It’s not yet clear which way Youngstown’s future lies — in the nascent hopes of its downtown and the high-tech possibilities of enterprises like NAMII, or in the much surer money of shale oil. One thing it will need for sure is the stubborn persistence of people like Ian Beniston and Mike Ray, people who stick with their city against the odds and will do their best to keep it going.

“This is home,” Ray said. “As tough as it gets, you don’t want to give up on it.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Sarah Goodyear has written about cities for a variety of publications, including CityLab, Grist and Streetsblog. She lives in Brooklyn.

Sean is a photographer based in Ohio. His work has been featured in a wide variety of publications including the San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Magazine and The New Republic.

He is currently working on a solo photographic exhibit, The People of Youngstown, for the Butler Museum of Art in Youngstown.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine