Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Anna Clark

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEditor’s Note: This is an adapted excerpt from chapter 6 of THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books on July 10, 2018.

The people in the city of Flint are resilient and we’ve created our own paths to resolve this problem.

—Claire McClinton (2016)

Though he is barely more than fifty years old, somewhere deep in Marc Edwards there burns the fury of an Old Testament prophet. He is a tall, lanky man — he runs most every day — with brown hair, silver wire-rimmed glasses and an enviable amount of get-it-done energy. But he carries himself heavily. His temper has become infamous in his field, erupting at the perceived moral failings, hypocrisies and errors of others.

Edwards grew up on the shores of Lake Erie in western New York when it, the shallowest of the Great Lakes, was a symbol for the emerging environmental movement. After decades of bearing the detritus of industry, agricultural pollution and human sewage, huge swaths of the 9,910-square-mile lake were declared “dead.” When Edwards was five years old, the slick of oils and chemicals on the Cuyahoga River, which empties into Lake Erie, caught fire. Dr. Seuss, in his 1971 children’s book The Lorax, imagined a toxic place where “fish walk on their fins and get woefully weary in search of some water that isn’t so smeary. I hear things are just as bad up in Lake Erie.”

From his tiny town, where children attended a K-12 school housed in a single building, Edwards remembered the foul smell of the lake and the ominous absence of fish. But, as he would tell the story later in life, he also remembered environmental engineers who worked feverishly to clean up the lake, part of a youthful movement that led to reforms that limited water pollution. The Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency were among the biggest triumphs, debuting not long after the nation celebrated the first Earth Day. Lake Erie had a remarkable recovery. Because it is far less deep than the other Great Lakes, it is still a harbinger for environmental woe, but there was enough improvement to inspire two Ohio State University graduate students to write Theodor Geisel, otherwise known as Dr. Seuss, in 1985. They invited him to Cleveland to see the renewal for himself and asked him to remove the dig from his book. The author declined the trip, but said, “I do agree with you that my 1971 statement in the Lorax about the condition of Lake Erie needs a bit of revision. I should no longer be saying bad things about a body of water that is now, due to great civic and scientific effort, the happy home of smiling fish.” He made good on his promise to take the line out of future editions.

Virginia Tech environmental engineering professor Marc Edwards testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., in 2016. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

When the time came for Marc Edwards to choose a major at the state university in Buffalo, he opted for biophysics. Meanwhile, one of the most significant environmental catastrophes of the twentieth century was playing out just twenty miles from Buffalo. It steered Edwards toward his life’s work.

In the summer of 1978, in Niagara Falls, New York, residents of a neighborhood called Love Canal were making national news by protesting the toxic dump they lived on. Love Canal was designed as a model community near the shores of the Niagara River, which links Lake Erie with Lake Ontario. Love Canal’s memorable name came about when an entrepreneur named William T. Love designed a clay-lined canal that was supposed to branch off the river, bypassing Niagara Falls. But the project was never completed. Instead, the area became a dump site in the 1940s and 1950s for about 21,000 tons of chemicals contained in 55-gallon drums, some of which were already corroding when workers put them in the ground. After covering the mess with dirt, the Hooker Chemical Company sold the site to the Niagara Falls Board of Education. The price: one dollar and a signed waiver that excused the company from all liability. The board knew that the site contained dangerous chemicals, but Niagara Falls was growing fast and it was in desperate need of affordable land for a new elementary school — which was built right on top of the dump. Soon the school was surrounded by hundreds of new family homes. None of the homeowners were told about the toxins seeping through the ground beneath them.

Twenty-some years later, vigorous reporting by a Niagara Gazette reporter shed light on what was already obvious to Love Canal residents. Miscarriages, birth defects, epilepsy, asthma, migraines and cancer were alarmingly common in the neighborhood. So were dying backyard plants, bad odors and even, after steady rain, the sight of old drums of toxic waste poking through the earth. One resident, Lois Gibbs, emerged as a powerful leader after her son, a kindergartner, developed epilepsy and a low white blood cell count. Gibbs mapped the health problems; led demonstrations; and, along with her neighbors, called for an evacuation of the entire development. New York State finally intervened after studies by the Environmental Protection Agency and the state’s Health Department confirmed that there were toxic vapors in the Love Canal houses. The elementary school closed. Families were evacuated from 239 homes, which were demolished over the next several decades. In time, a second school was closed and President Jimmy Carter declared it a federal disaster. It was the first time that a man-made emergency had been designated as such. In 1980, as a result of the community’s frontline activism, the Love Canal evacuation zone was expanded to include up to nine hundred more homes.

The Love Canal movement pushed the nation to reflect on how it should reconcile its industrial past with public health and environmental wisdom. Even Jane Fonda’s Workout Book, America’s number-one bestseller for more than six months in 1981, discussed the crisis at length in a chapter called “The Body Besieged.” (Fonda toured Love Canal with Lois Gibbs in 1979 and she also funded a speaking tour for Gibbs.) In Washington, the Carter administration developed what became known as the Superfund program to pay for the careful and comprehensive cleanup of toxic waste. Significantly, polluters were liable even if their dumping had been legal at the time.

Marc Edwards had found his field. The engineers working to solve the Love Canal disaster were heroes and he very much wanted to be seen as a hero, too. He eventually found his academic home at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, commonly known as Virginia Tech.

In January 2004, years before the water in Flint, Michigan, made national headlines, residents of the nation’s capital woke up to an alarming headline in the Washington Post: “Water in D.C. Exceeds EPA lead limit.” There had been elevated lead in the water for years — residents had discovered it, pooled their tests results together to create a database, mapped it and tipped off the Post — but this was the start of the explosive public revelations. Edwards had been part of the group looking into the issue. He worked on the case as a subcontractor for the EPA and shortly before the story became front-page news, D.C.’s water utility offered him a consulting contract. But by that point, Edwards had become so disgusted by its handling of the water problems that he refused it — he felt as if he would be working for the wrong side. He continued on as a volunteer.

His expertise on lead infrastructure and drinking water turned out to be an asset to residents who were pushing for answers. Once the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a now-infamous report — it claimed that no one was harmed by the contaminated water, even in homes that had more than 300 parts per billion of lead — Edwards became fixated on refuting it, especially as the report began to be used around the country to justify relaxed standards for drinking water.

For the galvanized community, the resolution to the D.C. water crisis was slow, iterative and never wholly satisfying. After the Post began reporting on it, the city’s Health Department launched a massive, albeit piecemeal, campaign to protect people from unsafe water. By 2006, the lead levels had lowered significantly, thanks to adjusted treatment. (Pre-flushing, a sampling technique that makes it seem like there is less lead in the water, was still used, though, which prompted many to question the test results.) There was another uptick when the city began doing partial-line pipe replacements. Replacing only part of a service line disrupts the section that remains in the ground. That can cause a spike in lead levels that lasts for months.

Edwards doubled down on researching the catastrophe. Along with other community organizers, he filed endless public records requests over many years to see if the rise in lead levels had, in fact, harmed children. He was met with obstinacy at nearly every step — the CDC and other agencies refused to provide him with information about the community’s blood-lead levels during the years when there was especially high lead in the water. When Edwards sent requests under the Freedom of Information Act for the raw data of the CDC report, he got nothing meaningful back, for years.

In early 2008, Edwards was finally able to evaluate information from the Children’s National Medical Center. In a peer-reviewed paper published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology in January 2009, he and his coauthors shredded the conclusions of the CDC’s earlier report. The data proved, as he later described it, “what we’d known actually for two thousand years. Which is, if little kids drink high lead in drinking water, they get lead poisoned. They get hurt.” Hundreds of children — maybe even thousands of them — had been lead-poisoned after being exposed to D.C.’s water during the years of contamination. In the most high-risk area, the number of children with elevated blood-lead levels had more than doubled.

In 2010, a bipartisan congressional investigation into the D.C. lead-in-water crisis confirmed what Edwards and the frontline community organizers had been arguing for years. Its unequivocal report was titled “A Public Health Tragedy: How Flawed CDC Data and Faulty Assumptions Endangered Children’s Health in the Nation’s Capital.” In 2004, it alleged, while worried residents were demanding answers, the CDC had rushed the report to publication, knowingly using incomplete data to tamp down the public outcry. As its senior author wrote in an email to her boss at the time, “Today has been the first day in over a month that there wasn’t a story on lead in water in the Washington Post and also the first that I haven’t been interviewed by at least one news outlet. I guess that means it worked!”

The investigation gave a jolt to the coalition that had been campaigning for safe water. Yanna Lambrinidou, a leading organizer who helped bring the new research to the attention of Congress, told a Post reporter that the shameful 2004 report “gave the perpetrators of D.C.’s lead crisis a ‘get out of jail free’ card,” allowing them to escape accountability for their actions for too long. Ultimately, the CDC backpedaled, but it never admitted to conscious wrongdoing. It was all a miscommunication. “Looking backward six years,” said the deputy director of the CDC’s national center for environmental health, “it’s clear that this report could have been written a little better.”

Flint, Mich. resident LeeAnne Walters testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., in 2016. (AP Photo/Molly Riley)

Edwards couldn’t let it go at that. He wanted the agency to admit that it had purposefully minimized the risk of lead in the water, perhaps because the CDC was worried about distracting attention from its long-running campaign against lead paint. Regardless, the crisis in the nation’s capital had real-world consequences. Two-thirds of more than six thousand tested homes showed lead levels that exceeded the federal limit. Hundreds of children had elevated lead in their blood, which was associated with the water. About $100 million were spent on partial-line replacements until it came to public notice that children living in homes that received one were even more likely to test for high lead levels. And in 2014, Edwards published a study that showed a correlation between the lead-contaminated water and a spike in fetal deaths and reduced birth rates.

The whole episode took a toll on Edwards. Even with the validation that came from his MacArthur “genius” grant and the congressional investigation, he was shaken by how difficult the fight had been. There seemed to be enemies everywhere. People in power were working harder to protect themselves and their institutions than to do what was right, he felt, which seemed to him to be an utter betrayal of public trust. “Overall, this was a time of just incredible hopelessness for me,” he said.

Believing that ethics was a crucial part of educating the next generation of scientists and engineers, Edwards teamed up with Yanna Lambrinidou, the parent and medical anthropologist who was an influential organizer during D.C.’s lead crisis. They began teaching a path-breaking graduate course at Virginia Tech called “Engineering Ethics and the Public.” It was designed to prepare students, still at the sunny beginning of their careers, to act when — not if — they are faced with a moral dilemma. Uniquely, it emphasized the voices of marginalized communities that were affected by the decisions made by engineers. One of the signature assignments was to role-play the press conference that took place after the Post story broke, featuring representatives from the EPA, the CDC, the D.C. water authority and other agencies. Armed with the same information those agencies had at the time of the actual conference, students found that they went so far in defending the office they represented, they sometimes invented information on the fly to counter questions they couldn’t answer.

For all that Edwards, Lambrinidou and many others had done to expose the D.C. crisis, nothing really changed afterward. No one was formally held accountable, not in a courtroom or anywhere else. Nobody was fired or demoted. There was no remediation, reform, or even any real apology. Even after the CDC finally backed away from the 2004 report, it admitted to being guilty only of bad writing. Meanwhile, water infrastructure across America was underfunded and in terrible condition and nobody seemed to care. And the loopholes in the federal Lead and Copper Rule were still there to be exploited when utilities tested their water, in D.C. and in cities all over the country. People were unknowingly put at risk every day.

Which is all to say that Marc Edwards could not have been more ready for LeeAnne Walters’s call from Flint, Michigan in the spring of 2015.

The only reason there wasn’t more data beyond LeeAnne Walters’s house was because “the City of Flint is flushing away the evidence before measuring for it.”

From the switch to the Flint River to her son’s lead poisoning, LeeAnne Walters brought Edwards up to speed on the water crisis. Edwards knew that the only way to find out what exactly was going on in the water at her home was to test it. Although tests done by the city and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality had already shown excessive lead, Edwards was all too familiar with how the analysis could be manipulated. It was worth doing the tests again and making sure they were analyzed the proper way.

So in April 2015, following instruction from Edwards, LeeAnne collected thirty samples from her home. The water had been shut off at this point for its excessive lead levels, so it had to be temporarily turned back on and in this unusual case, since it had been sitting stagnant for weeks, it was necessary to flush the taps at low flow for twenty-five minutes the night before. Over the phone, Edwards talked LeeAnne through the whole process: she didn’t let the water run first and she collected samples at a variety of flow rates — not the slow trickle that’s often used to lessen the likelihood of lead flaking from the pipes. The bottles were sealed and passed on to the EPA’s Miguel Del Toral. While he was traveling, the water manager who had been in communication with the Walters household personally dropped them off more than five hundred miles away, at Edwards’s lab at Virginia Tech.

Within a week, the results were in. The sample with the lowest lead level tested at 300 parts per billion; the highest was more than 13,000 ppb; and the average was 2,000 ppb. The EPA classifies water with 5,000 ppb as toxic waste. Even the low test far exceeded the federal action level. As Edwards relayed to both LeeAnne Walters and Miguel Del Toral, it was the worst lead-in-water contamination that he had seen in more than twenty-five years.

The EPA had been told that Flint’s water was treated with corrosion control, which helps to keep metals from the water mains and pipes from contaminating the water as it passes through. Del Toral had passed that assurance on to LeeAnne. But the only possible explanation for the state of her water was that it wasn’t. LeeAnne tracked down public documents that suggested as much and after making more inquiries Del Toral confirmed their suspicions. Pat Cook, a drinking water official with the MDEQ, told him that Flint hadn’t had corrosion control since “the disconnection from Detroit.” As Del Toral wrote in an email, this “is very concerning given the amount of lead service lines in the city.”

In the meantime, the city began to install a new copper service line to LeeAnne’s house. Del Toral seized the opportunity to examine the old line, confirming that it was made of lead. Downstream, he also retrieved a sample of galvanized iron pipe that had become coated with lead. Lead corrosion had flowed through it and stuck to the sides; if rust crumbled into the water, the lead would come with it.

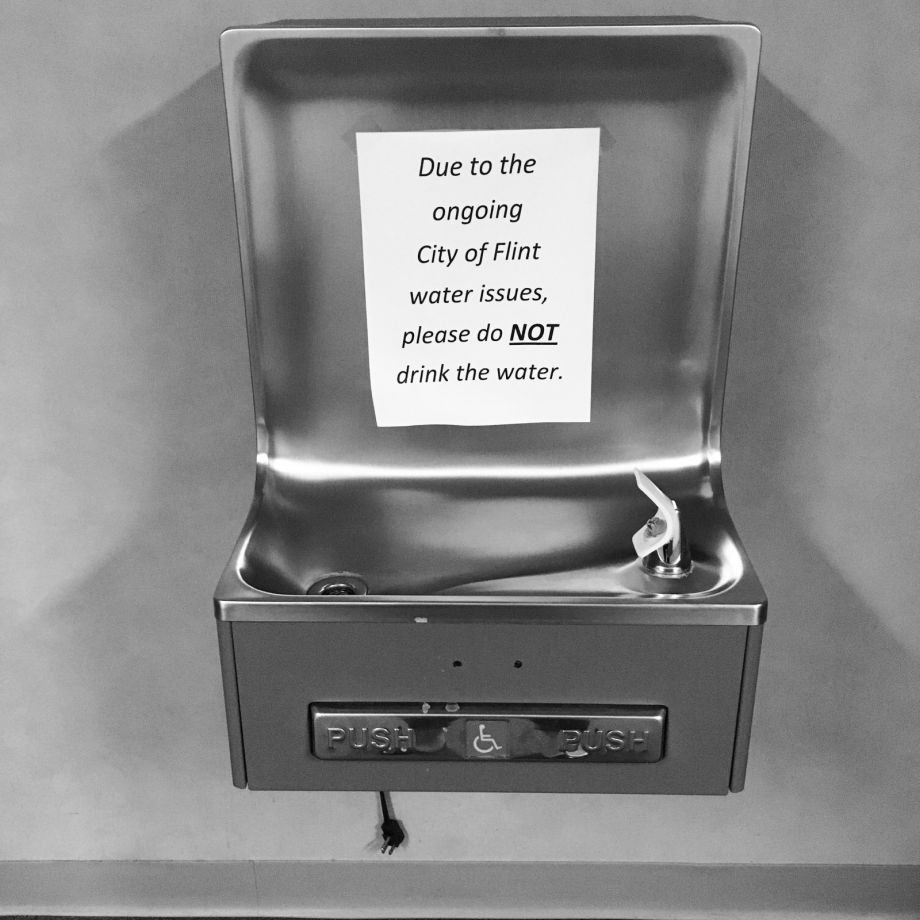

A note on a public water fountain advises against drinking Flint water. (Photo by Anna Clark)

It was increasingly obvious that the MDEQ’s pat voicemail to the EPA, which had attributed the Walterses’ problem to their indoor plumbing, was wrong. The surge of lead had to be coming from outside — and that lead service line was the likely culprit. Since similar lines threaded through all of Flint and since the contamination in the water at this house had hit hazardous waste levels, any rational person would wonder about the safety of the entire city’s water. Perhaps most damning of all for the MDEQ’s initial assessment were the results of tests done in May, after the new copper line was installed. The samples showed a dramatic improvement in the water.

Altogether, though, there was enough evidence for Del Toral to feel that it was time to issue an alert. He synthesized the saga in an eight-page report titled “High lead levels in Flint, Michigan.” It was confirmation of the contamination in the Browning Avenue household and an indictment of the overall management of the water the city had been drinking for more than a year. The report also documented Flint’s earlier problems with E. coli bacteria and TTHMs, a carcinogenic disinfection byproduct. Del Toral bluntly stated that after the switch from Detroit, Flint did not continue to treat the water in a way that would mitigate the lead and copper levels. It was both against the law and a threat to public safety.

Additionally, Del Toral’s report explained that the city’s water tests were unreliable. “The practice of pre-flushing … has been shown to result in the minimization of lead levels in the drinking water,” he wrote. “Although this practice is not specifically prohibited by the LCR, it negates the intent of the rule to collect compliance samples under ‘worst case’ conditions, which is necessary for statistical validity given the small number of samples collected.” Del Toral noted that the MDEQ supported the practice of pre-flushing. But Flint was now flirting with a public health emergency. He urged the EPA to intervene by reviewing the suspect sampling and the lack of corrosion control.

The report was addressed to Tom Poy, head of the groundwater and drinking water branch of the EPA in Chicago. Seven others were copied on it, including four MDEQ officials. Two EPA water experts were also listed as recipients, as was Virginia Tech’s Marc Edwards. When Poy followed up by asking why Del Toral was so certain that the lead problem was widespread, given the narrow set of tests, he was told that it was basic chemistry. “We don’t need to drop a bowling ball off every building in every town to know that it will fall to the ground in all of these places,” Del Toral wrote in an email. The only reason there wasn’t more data beyond LeeAnne Walters’s house was because “the City of Flint is flushing away the evidence before measuring for it.”

Then he got even more pointed: “I understand that this is not a comfortable situation, but the State is complicit in this and the public has a right to know what they are doing because it is their children that are being harmed. At a MINIMIM, the City should be warning residents about the high lead, not hiding it telling them that there is no lead in the water. To me, that borders on criminal neglect.”

When an employee writes a report like this, the EPA has a protocol. Its conclusion needs to be checked and rechecked before the agency signs off and releases a final version. Del Toral’s dispatch was thus considered an interim draft. But time was precious. If his analysis was correct, the corrosion of Flint’s pipes was worsening every day, causing more lead to saturate the water and more exposure to a dangerous neurotoxin. That’s why Del Toral had sent copies to the people at the MDEQ who were directly involved with Flint’s water. And when LeeAnne Walters asked for a copy, he gave her one, too. She, in turn, shared the report with a journalist she trusted. The Flint water crisis, a local worry for more than a year, was about to move into the spotlight.

Excerpted from THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, by Anna Clark. Published by Metropolitan Books on July 10, 2018. Copyright © 2018 by Anna Clark. All rights reserved.

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in Elle Magazine, the New York Times, Politico, the Columbia Journalism Review, Next City and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book. She has been a Fulbright fellow in Nairobi, Kenya and a Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books in 2018.

Follow Anna .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine