Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThe 60-square-foot room Boubacar Balde calls home is packed to the brim. A low double bed fills most of it, while a mini fridge and a scuffed nightstand crowned with a TV take up the rest. Near the bed, a small portable radiator hums beside a worn foldout table the size of a notebook. In the corner, a stack of newspapers and books supports a rolled-up, blue-and-gold prayer rug. A piece of lined paper taped to the otherwise bare wall reads Fonder Une Famille. Amoureux Dieu. The words remind him, each morning, of his two ambitions: To have a family and to love god.

Balde’s space is one of a dozen rooms in an illegally converted house in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx. He moved into the building more than a year ago in a bid to escape an even denser living situation. After legally emigrating from Guinea two years ago, Balde lived in a two-bedroom apartment he shared with five members of his extended family. He and two others slept in one room while a cousin and his young family lived in the other. They lived in shifts — some would work during the day and others at night.

After nearly a year, the 35-year-old taxi driver and former math teacher grew tired of the chaos and decided to move. But like many new immigrants, he faced an ever-rising cost of living in New York City. Even though he worked six nights a week, Balde still couldn’t afford the steep rents.

He finally found a room in an old, narrow brownstone on Bruckner Boulevard, on a block lined with the crumbling facades of dozens of converted houses brimming with tenants. Once a single-family home, the building has since been dissected into single room occupancy (SRO) units offered at a fraction of the cost of a full apartment. Each of the three floors had four rooms, a kitchen and a bathroom for shared use. At a modest $80 per week, the room was Balde’s most affordable option.

“I don’t have another choice,” Balde said. “That’s why I’m here.”

The home’s illegal conversion means that some of the windows don’t open, several fire exits are blocked and spaces are overcrowded. But most tenants have nowhere to go and are careful not to draw attention to the building’s infractions. A few months ago, an inspector caught up with Balde in front of his building and tried to ask if he lived there. Like most others, Balde knew the right answer.

“If they ask,” he said, “you don’t live here.”

The story of single room occupancy is, in essence, a story about the complex relationship U.S. cities have with their poorest and most transient residents. SRO was born out of urban overcrowding as cities scrambled to meet housing demands produced by industrialization and the urban population explosion of the early 20th century. But over time, SRO evolved from a cramped but affordable housing option for the working class into a poorly regulated last resort for the most desperate populations.

In New York City, the shift happened as a result of changing demographics and an ideology in flux. First, cultural norms began to favor single-family homes and discourage smaller dwellings. City regulators, motivated by a deep belief that SROs subjected tenants to substandard housing conditions, banned all new construction of single-room housing in 1955 and made it illegal to divide up one- or two-family houses into SROs. The idea was to gradually phase out these small units — viewed as improper and unsafe — and replace them with higher-standard alternatives.

Since then, the number of legal SROs in New York City has dwindled dramatically, with some 175,000 units disappearing between the 1950s and today. Single-room dwellings also fell out of favor in other urban centers across the country, which led in the loss of nearly 1 million SRO units nationwide. Between 1960 and 1980, Chicago lost 80 percent of its 38,845 SROs, while Seattle saw 15,000 units disappear. In San Francisco, more than 10,000 units were converted or demolished between 1960 and 2000.

In the gap between the supply and demand for affordable housing, a thriving sector of illegal SROs has developed. These units, which operate entirely outside the regulatory reach of city officials, have become increasingly common in the Bronx, where nearly 80 percent of people rent. Bronx residents — about 30 percent of whom live in poverty — also spend on average about a third of their incomes on housing, the highest percentage citywide. (According to a report by NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, rents in the Bronx averaged $1,008 per month in 2010, about 10 percent higher than what they were five years prior.)

“It’s an issue of a demand that is being unmet by the housing market,” said Harold Shultz, a senior fellow at the Citizens Housing and Planning Council, a non-profit research group that aims to improve housing conditions in the city. “There’s a lot of single people looking to rent and they don’t have a lot of money.”

Today, experts estimate that there are more than 100,000 illegal SROs across the city, in addition to 30,000 legal units. Many of them are unsafe, with too many people living in too small a space. Often, they lack proper fire exits and ventilation — safety issues that Rafael Salamanca, district manager for Bronx Community Board 2, said make many illegally converted dwellings in his district problematic.

Balde understands this problem intimately. In his SRO, the tiny window doesn’t open. If there is a fire in his third-floor bedroom, the only way out is a fire escape in another tenant’s room.

“I don’t know how safe I feel,” he said. “If there’s a fire, where do you go out of?”

In the last 15 years, several major blazes have taken lives. In one case two years ago, a Mexican immigrant family died when an early-morning fire engulfed an illegally converted brownstone in the Belmont section of the Bronx. The tenants, a couple and their 12-year-old son, could not reach the fire exit from their room on the second floor of the house.

“The problem is that the people of the ’50s imagined everyone would prosper and be able to afford good housing,” said Brian Sullivan, an attorney with the SRO Law Project at MFY Legal Services, a non-profit firm that represents low-income tenants in housing claims. “So the number of legal SROs plummeted catastrophically over the last 50 years, without any real sense of alternatives.”

Despite the utopian dreams of mid-century planners, poverty in New York has persisted and even worsened — today nearly a fifth of New Yorkers live in poverty, compared to less than a sixth in 1969. Meanwhile, changing gender and family norms have meant a massive increase in the number of single-person households in the city, which rose from 185,000 in 1960 to more than 700,000 in 1987 to an estimated 1.8 million today.

In 1985, as the city’s homeless population reached unprecedented levels, policymakers began trying to preserve whatever remained of the SRO housing stock. Tax incentives meant to prompt owners to turn their SROs into larger homes were replaced by new programs that offered tax breaks to owners willing to keep and improve their existing multi-unit dwellings. Programs offering low-interest renovation loans to owners of SROs were also introduced. Then-mayor Edward Koch even tried to pass a moratorium on conversions and demolitions of SROs, but the state Court of Appeals eventually overturned the bill, ruling it unconstitutional.

“In a way, the whole government policy has gone full circle,” said Hank Perlin, a former tenant organizer for the West Side SRO Law Project and now a senior financial analyst with the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. “At first, the government was encouraging developers to convert SROs and providing incentives to do so. Now that all the SROs are gone, it’s providing incentives to developers to make new SROs.”

The story of single room occupancy is, in essence, a story about the complex relationship U.S. cities have with their poorest and most transient residents.

Even as for-profit development of new SROs remained illegal, policymakers attempted to relieve some of the demand for single-room housing by allowing development by non-profit churches, community centers, mental health networks and homelessness advocates. Today, there are about 30,000 legal SRO units throughout the five boroughs, representing approximately 8 percent of the city’s housing market. City codes define them as one-bedroom dwellings that usually share bathroom and kitchen facilities with another half-dozen units. By law, rooms must be at least 150 square feet and have a window and accessible fire exit. Tenants have to be at least 16 years old. No more than one person is permitted per room.

But due to shrinking resources at the city and state levels, that the supply of SRO housing has failed to grow at the rate of demand. The high costs of subsidies and tax exemptions mean that the city can only develop a small number of units for an ever-growing population in need of affordable housing.

“The housing that we develop, it’s expensive,” Perlin said. “It’s a lot cheaper to preserve existing privately owned units and enforce codes… than it is to develop new units.”

This struggle came to the fore late last year when Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a major rethinking of the city’s attitude toward housing. Citing the rising cost of studio apartments, he pitched a new type of housing that he claimed would balance adequate standards with affordability: the micro-unit.

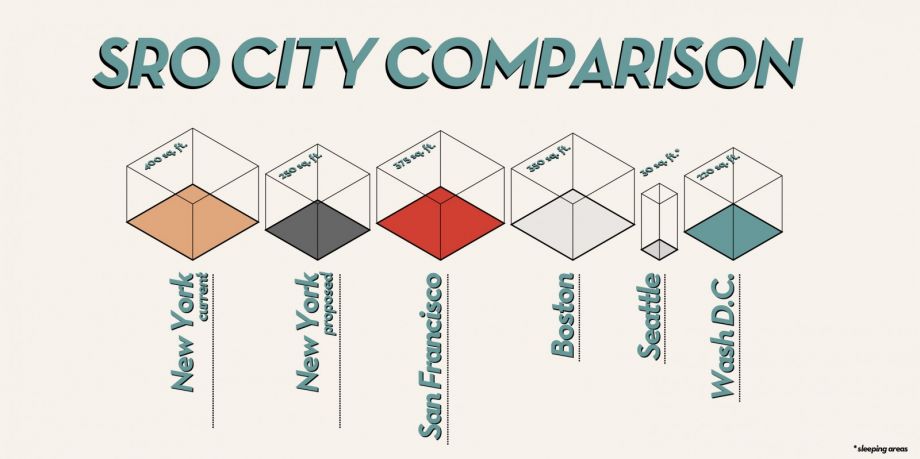

The micro-unit is a very small apartment ranging in size from 250 square feet to 320 square feet. While cramped living quarters are nothing new in New York, the concept of creating an entire stock of teeny apartments is unprecedented. To build an entire development composed of these units, the city had to exempt itself from zoning regulations that demand the average apartment size in a new building be at least 400 square feet in size.

In essence, Bloomberg had to snip away some of the red tape imposed as part of last century’s war on SROs. He wanted to create a new kind of single-room unit. What he created was a unit for the millennial generation.

The micro-unit was an entrepreneur’s answer to the affordable housing crisis. Instead of creating more vouchers or rental assists, Bloomberg created a new product to respond to a growing market of single adults.

“The growth rate for one- and two-person households greatly exceeds that of households with three or more people, and addressing that housing challenge requires us to think creatively and beyond our current regulations,” Bloomberg said in a January press release.

The city held a competition intended to attract high-level architect and developer teams to the task of designing a new model for small, urban, affordable housing. The prize was the right to develop a tower of mini-units on one of Manhattan’s few undeveloped, city-owned parcels — a parking lot in the Kip’s Bay neighborhood on the East Side.

Perhaps due to the value of the property and the high-profile nature of the project, the competition generated a huge response and the city received 33 applications — roughly three times the usual number for a project of that magnitude. Developers around the world downloaded the Request for Proposals from the city’s website some 1,600 times. A development team comprised of Monadnock Development, Actors Fund Housing Development Corp. and nArchitects ultimately won the competition with its “My Micro NY” proposal, which relies on premade “modular” construction. The units, to be built off-site while the lot is prepared, allow for faster, cheaper construction that the team has deemed “the secret ingredient” for this type of small-scale housing development.

With their modern, streamlined design, individual kitchens and bathrooms, Juliette balconies, and shared rooftop garden, the micro-units are more like miniaturized condos than traditional SROs. They are also far less affordable. The building will contain 55 units, 40 percent of which will be rented below the standard market rate, according to officials. Eleven will be rented for approximately $940 per month to families that earn at least 20 percent less than the area’s median income. Another 11 units will also have income restrictions and will be rented for $1,700 to $1,800 per month. The rest of the units will be rented at market rate and will cost more than $1,800 per month.

“These units are below market but [they are] still not affordable to somebody who can only afford $800,” said Jill Hamberg, a professor at Empire College and urban planner who has worked on SRO legislation in the past.

Yet through the initiative, Bloomberg has opened a door to a potential loosening of the regulations that prevent other kinds of small housing from being developed. “If the pilot is as successful as we think it will be, it will help make the case for regulatory changes to meet the housing demands of the 21st century,” Bloomberg said at a January press conference following the announcement of the competition winners.

The micro-unit is a very small apartment ranging in size from 250 square feet to 320 square feet. While cramped living quarters are nothing new in New York, the concept of creating an entire stock of teeny apartments is unprecedented.

If lasting changes are made, New York will join several other cities that have already embraced the concept of building smaller efficiency units to meet affordable housing needs. Last November, San Francisco policymakers amended the city’s building code to allow the construction of 375 units measuring just 220 square feet, with plans to allow for more later on. In Washington, D.C., where the minimum size requirements is 220 square feet, officials are currently reviewing proposals for a mixed-use development that will include 200 micro-units. Boston officials have reduced building size requirements to 350 square feet but have restricted development of micro-housing to the city’s “innovation district.”

Perhaps the best example of building small can be found in Seattle, which introduced micro-housing in 2008 and has seen the development of 2,300 units since then. The city’s residential code currently doesn’t include minimum size requirements and allows the construction of units with sleeping areas as small as 30 square feet. The units contain individual bathrooms and share kitchen facilities with other tenants, much like traditional SROs. The rents range from $525 to $700 per month. The average renter of these units earns less than $24,000 per year, according to developers.

Seattle City Councilmember Nick Licata said the units have provided a safe, affordable housing option for the city’s low-income population. Although the developments have triggered some criticism because of their minuscule size, Licata said they have helped address the city’s shrinking vacancy rate.

“Right now Seattle is the fourth hottest real estate market in the country,” Licata said. “We have a situation where we have a growing demand for housing, and our [affordable] housing stock — even though we’re building more and more apartments — is still not keeping up… As a result, these apartments fit a perfect niche.”

While micro-units continue to capture the public’s attention, illegal SROs remain in the shadow. Citywide, the New York City Department of Buildings receives about 20,000 complaints of general illegal conversions each year, said department spokesperson Tony Sclafani. The fine for an illegal conversation typically hovers around $2,400, but a repeat offender can pay up to $25,000. If the dwelling presents a serious threat, city inspectors can also issue a vacate order that requires tenants to leave the building immediately. Last year, inspectors issued 1,200 such orders to buildings that lacked fire exits and posed an immediate hazard to tenants.

It’s very likely, however, that many other unsafe dwellings evaded notice. If inspectors cannot gain entry to a house after two visits, they must close the case. Last year, only 46 percent of buildings that received complaints about illegal conversions were inspected, according to a September 2012 report from the Mayor’s office.

Edward, who asked for his last name to be omitted for fear of reprisal, is a former chief inspector who spent more than a decade with the Department of Buildings before resigning a few years ago. During his career, he often saw how the department’s rules halted efforts to properly enforce the housing code. Countless times, a complaint had to be dropped because a savvy landlord wouldn’t open the door in hopes of evading an inspection.

“It’s very difficult to actually write an SRO violation in New York City,” Edward said. “Unless you actually physically see the spaces, it’s very difficult to declare it an SRO.”

When he was able to get inside, Edward saw dangerously blocked fire exits and overcrowded rooms housing whole families. But the decision to evict was always the hardest. Although the Red Cross often puts up tenants temporarily in hotels following an eviction, most are left with nowhere to stay for the long term, having been effectively rendered homeless.

“When you’re doing an inspection and you start evicting people and they tell you, ‘I got no place to go,’ it’s difficult,” Edward said. “But the safety factor is tremendous. These places are very unsafe. You actually go in there and save lives. That’s what people don’t understand.”

The night Hurricane Sandy struck, Jerry Vargas woke up to the sound of water rushing in through the small windows of his basement SRO unit in the Rockaways. Within minutes, his room was submerged. Vargas, 44, scrambled to safety on the second floor of a three-story building on Beach 115th Street.

After the storm, Vargas went back to survey the damage and found his 80-square-foot room filled with mud and sand. The plumbing system was destroyed and the walls were collapsing. Everything he owned was in ruins. Vargas, who has been living on disability benefits since he was hit by a truck two decades ago, was left with no place to live.

“I couldn’t go back,” he said. “It was uninhabitable. It smelled like a sewer.”

The beachfront stretch between Beach 97th and 122th Streets in the Rockaways is home to countless SROs, which mostly provide housing to the neighborhood’s poorest residents. Many are hidden within pastel-colored, mansion-like buildings reminiscent of once-polished seaside villas. Others — tucked within modest, weathered two-story houses — were once the homes of single families but had since been subdivided into tiny rooms with about a dozen tenants each. Sandy reduced many of these SROs to rubble and mud, leaving tenants like Vargas homeless.

Vargas was among the lucky. After three months of bouncing between friends’ homes he found another room in another SRO. For many of the people who lived at his last home, the future is less certain. Rentals in this narrow sliver of land on the southern tip of Queens have become increasingly popular in recent years. Tenant advocates from Occupy Sandy and other groups say owners of SROs are using the de-facto evictions caused by Sandy as an opportunity to upgrade buildings for higher-end renters.

In one SRO visited by Aaron Dickerson, an Occupy Sandy outreach coordinator, a tenant was living with no water or heat because the landlord had, in an effort to drive him out, refused to turn utilities back on after the storm.

“People are living with no interior walls, with no water, with no kitchen,” Dickerson said. “A huge percentage just don’t know what their rights are. They don’t know that the landlord can’t just not turn the heat on.”

Vargas now lives in a 60-square-foot room on the third floor of a 30-room SRO, a stone’s throw from the beach. The room is bare save for a small bed, a pile of donated clothes and a weathered vanity with a cracked mirror. Vargas came back to the Rockaways reluctantly, mostly because he couldn’t afford anything else.

“Why go back to a place that’s doomed?” he said. “But how can I find another place if I have no money to find another place?”

If lasting changes are made, New York will join several other cities that have already embraced the concept of building smaller efficiency units to meet affordable housing needs.

That’s the central question for many of the city’s poorest residents. Aside from its micro-unit pilot project, New York City has upheld its ban on new for-profit construction of single-room dwellings over the years, despite warnings from critics who argued the private sector was the city’s only hope for significantly improving its affordable housing stock. Policymakers have been reluctant to allow developers to build for-profit SROs because of fears that these units would set a lower size standard and push the price of studios upward.

Meanwhile, SROs developed by non-profit organizations have been insufficient in meeting the housing needs of the whole city. Oftentimes the groups that receive permission to build SROs bring funding tied to special-needs tenants like homeless veterans, the mentally ill, domestic abuse victims or people with AIDS. Because of this, many new developments have only a few spots for the general low-income population. Some groups, like undocumented immigrants, are left out altogether.

“So the only alternative is to find a room in one of those illegal houses,” said Sanman Thapa, a tenant counselor with the Chhaya Community Development Corporation, a non-profit that aims to improve housing opportunities for South Asian immigrants.

“Illegal subdivision — it is a health hazard, it is a fire hazard, it is not safe,” Thapa added. “But at the same time, there is not really any other alternative. There isn’t enough affordable housing being built.”

But in order to make these units safer, they must be brought into the legal housing realm — a move that has proven unpopular with community groups weary of the dangers associated with SROs. For many New Yorkers, these units symbolize the advent of crime and poverty into their neighborhoods, said Larry Wood, a housing activist with the non-profit Goddard Riverside Community Center. In the 1990s, according to Wood, outcry from community associations in Queens was the primary reason then-speaker Peter Vallone rejected proposed code changes that would have allowed for the construction of smaller housing units. As the borough became richer, more and more residents wanted to safeguard its character and keep outsiders out.

“He was getting a huge pushback from homeowners’ associations in Queens saying, ‘we don’t want these buildings,‘” Wood said. “It was a lot of white homeowners saying ‘we don’t want our neighborhoods changing.’”

Nationwide, residents in areas like Chicago’s North Side and Atlanta’s Lake Claire district have also adamantly protested the development of SROs in their neighborhoods. In Seattle, outraged neighborhood associations have called for a moratorium on micro-housing development, which has forced policymakers to consider implementing stricter regulatory measures.

As the Bronx has seen more and more illegally converted SROs over the last few years, public opposition there has also gained traction. Following the 2011 fire in Belmont, residents of Morris Park began calling for better regulatory efforts aimed at curbing conversions. The neighborhood, which boasts one of the lowest crime rates in the city, is the kind of community where everybody knows one another and residents take turns patrolling the streets to ward off trouble. But in recent years, more and more of Morris Park’s neat single-family homes have been illegally converted into SROs, bringing transient and unfamiliar residents to the area. Al D’Angelo, president of the Morris Park Community Association, said illegal conversions are a major problem and residents worry they will change the character of the low-crime, middle-income neighborhood.

“It’s ruining the quality of life,” D’Angelo said. “The middle-class people are leaving the community. You’re taking a middle-class community and turning it into the South Bronx.”

“I know what’s good for the community,” he added. “And when you have multiple dwellings like that, it’s not good for the community. It has nothing to do with being racist, it’s about quality of life.”

Meanwhile, over the last four years the city has started cracking down on illegal SROs in a new way. Sclafani, of the Buildings Department, said the agency has focused on educating residents about the dangers of living in illegal units. The department has also, through a new high-powered multi-agency task force charged with shutting down particularly dangerous SROs, begun to carry out undercover operations in illegal dwellings.

Before the SRO, New York City had the tenement. As immigrants poured into the city in the 19th century, middle-class homes previously housing single families were chopped up again and again to accommodate more people. Apartments were linked together like train cars and the internal rooms were dark and windowless. Tenements were usually five or six stories with an average of 18 units, and prone to collapse and fire. By 1900 there were 80,000 tenements in New York City. Two-thirds of the urban population — about 2.3 million people — was crammed in these sunless and poorly ventilated dwellings, concentrated mostly in the Lower East Side.

Tenements were entirely unregulated until the latter part of the 19th century, when wealthier segments of the public began to take notice of their squalid living conditions. The city passed its first tenement law in 1867, requiring each building to have a fire escape. Twelve years later, another law mandated that each room have a window facing a source of fresh air and light. In the mid-1930s, the city began requiring tenement owners to replace stairways made of wood with ones that were fireproof. But the size or density of the tenements was never regulated.

“If you look at the hierarchy of law, the most important thing is fire safety,” said Morris Vogel, a historian and president of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. “The density is way down the list of rule-making, historically… They didn’t care if a thousand people lived in a space as long as it was fire-safe. As long as the city wouldn’t burn.”

Today, SROs are often referred to as modern-day tenements: Substandard, overcrowded, dark firetraps that represent the worst housing the city has to offer. Neighborhood associations in cities nationwide have protested the legalization of small dwellings, arguing that it would degrade neighborhoods and lower the quality of life. In cities like Seattle, critics fear micro-housing development will only erode standards and push up the cost of better housing.

To Licata, the Seattle city councilmember, there is a danger that demand for this type of housing may lead developers to build as small as possible and charge as much as the market will allow, which may indeed prove detrimental to housing standards. But right now, he said, it’s too early to tell.

“These micro-housing units are literally two or three years old,” Licata said. “We don’t know what the trend will be, we don’t know what impact it will have on the bigger housing market. I don’t think it has had any impact so far other than it has provided more affordable housing.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Mariana Ionova is a multi-platform journalist currently based in New York City. She is a recent graduate of Ryerson University’s journalism school in Toronto, Canada and has reported for Gotham Schools, the Ottawa Citizen, Metro News, the Eyeopener, the Ryersonian, the Toronto Star and the Bronx Ink. Currently, Mariana is pursuing a Master’s degree in digital media at the Columbia Journalism School.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine