Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

In his 2012 TED talk, venture capitalist and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman extolled the power of “network literacy” which is, he said, “absolutely critical to how we’ll navigate the world.” He continued, “In a networked age, identity is not so simply determined. Your identity is actually multivariate, distributed and partly out of your control. Who you know shapes who you are.”

If networks are the new, fast and partly-out-of-your-control vehicles for individual career building, could they also be the vehicles for building stronger economies and more livable communities in metropolitan areas? Today’s metro networks are different from the cadre of business elites, elected officials and technocrats that arose in the mid-20th century. They are larger, looser and more diverse both in terms of membership and their geographic span.

In Greater Denver, a coalition of urban and suburban mayors, private sector leaders and grassroots transit advocates helped push through financing for the country’s largest buildout of a public transit system since the Washington, D.C. Metro. In Northeast Ohio, a network of economic development organizations and local governments are helping to retool traditional economic clusters and sectors. Even in Greater Detroit, a metropolis long and deeply divided by race, new collaborations among business incubators and community colleges are working to grow (and prepare workers for) better jobs.

Networks like these have been slowly rising for some time, but they have never been better suited to our current political and economic moment. The realities of economic restructuring, global competition, fiscal pressures, environmental imperatives, technological possibilities and a dysfunctional federal government require new models of collaboration within and among metropolitan regions.

In the past, shortsighted battles over a new headquarters or big-box development have precluded metropolitan leaders from working toward their long-term goals and strategies. When metropolitan leaders did manage to work together, their efforts were oriented inward: How to allocate public resources fairly across a region, and how to create a level playing field between old jurisdictions and new ones.

Over the last few years, the conversation has changed. Local elected officials and others are also looking outward and understanding the metropolitan role in the broader national and global economy. As Colorado Gov. (and former Denver mayor) John Hickenlooper is fond of saying, “Collaboration is the new competition.” That’s true not only because collaboration is replacing competition on important issues in many metros, but also because metros have to collaborate to compete in the global economy.

Those metros that have created successful networks have certain characteristics in common. They are smart about their goals and how to measure them; confident enough to resist cookie-cutter strategies; sophisticated about their place in the global economy; clever about balancing short-term wins and long-term aspirations; and open to people representing a spectrum of groups, interests and sectors.

And while these are habits that any metro can adopt, there is, of course, an element of serendipity to their success. The most intriguing evolution of metropolitan leadership will happen via the application of new social technology — which is designed to create, inform and mobilize new, fluid and unpredictable networks. The result may be not only the crowdsourcing of innovative ideas, but the redefinition of “leadership” as a populist rather than elitist phenomenon.

“The collapse of the consumption-driven, domestic-focused growth model is giving rise to new thinking about a next economy that is fuelled by innovation, powered by low-carbon processes and products, driven by exports and rich with opportunity.”

When you look at global economic performance you’ll see that the top 30 metro performers today are almost exclusively located in Asia and Latin America. The 30 worst metro performers are nearly all located in Europe, the United States and earthquake-ravaged Japan. In 2009, Brazil, India and China (the BICs) accounted for about a fifth of global GDP, surpassing the U.S. for the first time. By 2015, the BIC share will grow to more than 25 percent. These nations are growing because they are urbanizing and industrializing. The locus of economic power in the world is shifting. How will communities in the United States compete — not just for rankings, but for the jobs, people and resources that make them good places to live?

They have to go big or go home. Competition with the rising powers and mega cities of the world is prompting a reevaluation of the size and scale at which communities compete. In the face of Mumbai (19.2 million people), Sao Paulo (18.9 million) or Shanghai (16.7 million people), the focus on the differences between suburban municipalities of 25,000 residents seems wasteful, if not absurd. U.S. metro leaders must re-imagine the size, shape, structure and orientation of their economies. The metro scale, and even the multi-metro and regional scale in certain places, is now the entry ticket to global competition.

The Great Recession was a wake-up call to American metro leadership. At its onset, many U.S. cities and metropolitan areas found themselves engaged in low-road economic growth, pursuing mall developers and condo builders, as if housing and retail were drivers of the economy rather than derivative of the sectors that truly generate wealth: Manufacturing, innovation and the tradeable export industries.

This consumption economy was mostly zero-sum. A dollar spent (and taxed) or a house built (and taxed), or a business located (and taxed) in one jurisdiction was lost to any other. So, in metropolis after metropolis, jurisdictions competed against each other for sources of tax revenue — usually commercial development and big employers — wasting scarce dollars on enticing businesses to move literally a few miles across artificial political borders. The result: Metros prioritized short-term speculation over long-term growth and sustainable development. They did this until the bubble popped.

The collapse of the consumption-driven, domestic-focused growth model is giving rise to new thinking about a next economy that is fuelled by innovation, powered by low-carbon processes and products, driven by exports and rich with opportunity.

These aspects of the next economy — particularly innovation — are the opposite of zero-sum. More innovation in one corner or sector of a metropolitan economy tends to yield more innovation, entrepreneurship and job creation throughout the metro. Metropolitan areas bring together people whose ideas intermix, recombine and explode in new directions. So metropolitan areas do not just produce more patents; the patents within metros tend to be cited and built on disproportionately by others in the same area.

Think about the film industry in L.A., or the computer and electronics sector in Portland. There are entire groups, or clusters, of related companies and institutions that benefit from the explosion of energy and innovation. A growing body of research suggests that being part of such an industry cluster is good for an individual firm; it makes any firm more innovative, and makes new firms more likely to survive. For example, clean-tech companies tend to grow much faster if they are in the same county as related businesses.

Just as being near productive people helps other people become more productive, proximity to clusters in one industry also tends to help other industry clusters get stronger. One study by Delgado, Porter and Stern finds that the relative strength of a U.S. region’s leading clusters contributes to the employment and patent growth of other clusters in the region. Another analysis, by Spencer and others, shows that metropolitan areas with a higher percentage of people employed in clusters have higher income levels and job growth overall than places with lower shares of workers in clusters.

It’s not only high-level workers within a particular industry who benefit from the industry’s growth. More innovation, from all these patents and clusters, leads to more exports — firms tend to export more after they innovate, because humdrum companies can’t compete on the global market. More exports lead to more jobs (often manufacturing jobs) that pay well for workers at a variety of skill levels.

Given the potential of metropolitan areas to use density as a tool for innovation, it’s ridiculous for cities and suburbs to continue to fight over the next big-box store or industrial park instead of collaborating to marshal the power of their innovative institutions, their skilled and rising workers, and their metro-wide supply chains.

If a zero-sum economy is one hindrance to metropolitan collaboration, another is the perceived demographic and cultural gulf between city and suburbs. Cities were supposed to be diverse, poor and dangerous. Suburbs were supposed to be homogeneous, cozy and rich. But as the U.S. undergoes a massive demographic transformation, that neat dichotomy is melting.

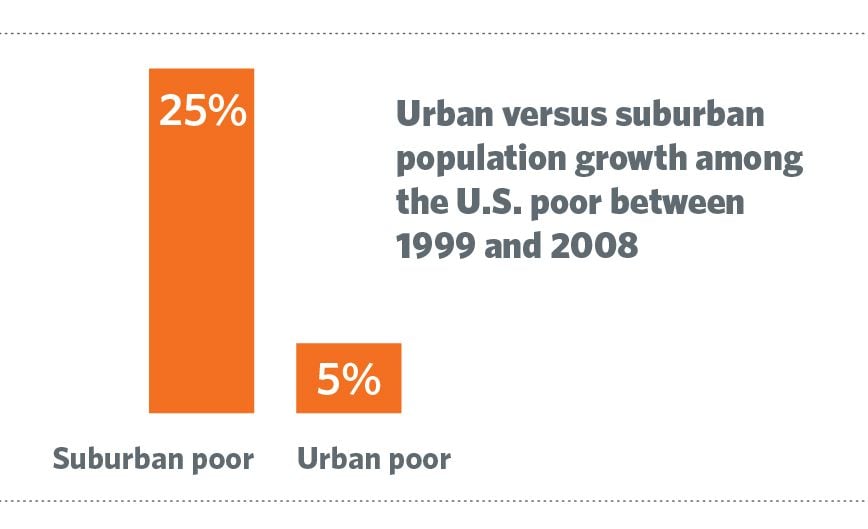

Over the past several decades, racial, ethnic and income disparities between cities and suburbs have radically diminished. As of 2008, a majority of members of all racial and ethnic groups in metropolitan areas lived in suburbs, as did more than half of all immigrants nationwide. During this same period, the poverty gaps between cities and suburbs also narrowed because of the growing suburbanization of poverty. The suburban poor population grew by 25 percent between 1999 and 2008, almost five times the growth rate of the primary city poor in that time. As of 2008, suburbs were home to almost one-third of the country’s poor population, and 1.5 million more poor people than the nation’s primary cities

Similarly, the gap between city and suburban violent crime rates declined in nearly two-thirds of metro areas between 1990 and 2008. In most metro areas, city and suburban crime rates rose or fell together.

That shared fate does not stop with demographics and crime rates. The post-recession municipal fiscal crisis has pressured cities and suburban municipalities to tighten their belts. While unfortunate, the pressure has laid the foundation for more metropolitan collaboration. In 2008, there were 181 such shared public service arrangements in New York State, according to a report from Office of the State Comptroller in New York. And while once considered only by particularly small or financially distressed communities, the collaborations are becoming more common. This past March, the City of Santa Ana disbanded its fire department and began paying surrounding Orange County to provide fire prevention services, following similar agreements made in Sacramento and the cities of Newark and Union City in the San Francisco Bay Area. That came after the city of Maywood, Calif., in 2010, disbanded its police department (and cut many other government services, like parking enforcement, entirely) and turned over the responsibilities to neighboring Bell, Calif. (which is charging Maywood $50,000 a month, saving Maywood $164,000 a year). In Virginia, officials from the cities of Chesapeake, Norfolk and Virginia Beach are exploring the benefits of similar shared public service arrangements.

Metropolitan areas now have no choice but to use networks to recharge their economies and remake their places. With the federal government paralyzed by dysfunction, state legislatures becoming increasingly partisan and state coffers still battered by the recession, metropolitan areas have to innovate, whether they like it or not. No other level of government is going to ride to the rescue.

While Washington dithers and delays, metros are innovating in ways that build on their distinctive competitive assets and advantages. With federal innovation funding at risk, metros like New York are making sizable commitments to attract innovative research institutions, commercialize research and grow innovative firms. With the future of federal trade policy unclear, metros like Los Angeles and Minneapolis-St. Paul are reorienting their economic development strategies toward exports, foreign direct investment and skilled immigration. Undeterred by a lack of federal energy policy, metros like Seattle and Philadelphia are cementing their niches in energy-efficient technologies. And metros like Jacksonville and Savannah are modernizing their air, rail and sea freight hubs to position themselves for an expansion in global trade. These metros have figured out some of the keys to ensuring strong leadership in tough times. So how did they do it?

Highly effective metropolitan networks have characteristics, or habits, than can be cultivated and replicated across the country. Generally, these networks embrace curiosity and creativity and shun complacency or despair. And though it sounds like a paradox, highly effective metropolitan networks use their shared habits to become less alike in other ways, as each pursues a path based on their unique mix of assets and obstacles.

1. Measure what Matters

Moneyball — Michael Lewis’ popular book and subsequent movie — documents the unique metrics developed by Oakland Athletics General Manager Billy Beane and his staff to assess offensive talent in baseball. The result: By using distinctive measures to assemble the right players, the lower-revenue Oakland A’s were able to successfully compete with the high-revenue, free-spending teams like the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox.

“Cities and metros in the pre-recession era were measuring the wrong things.”

This concept of measuring the “right” statistics applies equally well to successful regional economic development strategies as it does to baseball.

Cities and metros in the pre-recession era were measuring the wrong things: Speculation rather than innovation, parochial demand rather than global trade, real estate appreciation rather than productive returns. They were, in many cases, also measuring the same things: Housing starts, new commercial square footage and big-box store openings.

The post-recession period presents a historic opportunity to change how we measure growth and prosperity in metropolitan America and, by doing so, how we alter the trajectory of that growth. By measuring and gaining a more thorough understanding of their most important economic assets — through an analysis of export orientation, migration patterns, industry clusters, innovative capacity and human capital — metros will be better able to build on their strengths and compete in the global economy.

In a nice bit of geographic felicity, the Bay Area Council exemplifies the Moneyball approach to regional economic development. The council is a business advocacy organization for the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area region. Its Economic Institute has developed comprehensive data and policy reports in seven areas critical to the region’s economic success: Competitiveness, economic development, infrastructure, trade and globalization, science and innovation, energy and governance.

On trade and globalization, for instance, the BAC Economic Institute has published a series of reports on the linkages between the Bay Area and emerging economies like India and China. These reports analyze connections of trade, tourism, international student exchange, transnational networks and foreign direct investments, and have become a foundation for respected, actionable, up-to-date information about what the metropolis trades, and with whom.

Sean Randolph, the president of the Council’s Economic Institute, points to specific examples of how governments and others have applied the Council’s work:

“Airports use it to support expanded air service, and state and local agencies use it when exploring new policy options. The business community may be the biggest user, drawing on the Institute’s research to inform advocacy, develop opportunities (in China and India for example), and support strategic thinking at the firm level…. The key to the effectiveness of this process has been metrics, and the presentation of credible, fact-based analysis that can be used by a variety of constituencies.”

This is the right kind of data at the right geographic scale.

2. Dare to be Different

Exports, innovation and governance matter to all metros, but they matter in different ways. Detroit, for instance, has a different manufacturing and export profile than Denver. Pittsburgh has a different innovation ecosystem and entrepreneurial potential than Phoenix.

Over the past several years, colleagues at Brookings have worked with economic development consultant and RW Ventures President Bob Weissbourd, and a small number of metropolitan areas to invent a new practice for metropolitan economy building. We call them “metropolitan business plans.” Each business plan starts with an assessment of the same “levers” of economic activity: Concentrations of industries, functions and occupations; human capital; resources and institutions that support innovation and entrepreneurship; spatial efficiency; effective public and civic institutions; and information resources.

But the analysis of each of these elements leads to different conclusions about the directions different metros should take, and how they should achieve their goals. Northeast Ohio decided its business plan should focus on helping auto supply chain companies open up to new markets (such as medical devices and green energy). Minneapolis-St. Paul’s indicators showed that the region underperforms on entrepreneurship, so its business plan creates an entrepreneurial accelerator to provide networking, funding and mentor assistance to new businesses. The Puget Sound region aims to create labs and expertise to test and demonstrate new clean energy building technologies, based on data that showed strength in the clean sector and an opportunity to create an opportunity for workers in the region to gain additional skills.

Metropolitan business plans are not a vehicle for inventorying problems or writing “shelfware” strategies. Rather, they provide a way for metro leaders to act as an ongoing business enterprise, presenting prospectuses to invest in their regional economies. Similar thinking informs efforts elsewhere. New York State, for example, challenged 10 regional councils — public-private partnerships of corporate, civic, university, labor, environmental and local governmental leaders — to craft strategic economic development plans for their regions. The state made available $200 million in capital and tax credit funding and additional resources for particular projects were allocated via other state funding streams. In the end, a small review committee of senior government officials and outside experts selected the four best plans and gave them money to proceed.

With this, the traditional silo-driven, project-obsessed focus of economic development was flipped on its head. Local leaders got the responsibility to identify investment priorities that further the distinctive possibilities of their places. Then the state was tasked with getting behind the local strategies, crossing rule-bound bureaucracies and fragmented programs to get things done.

3. See the World

Throughout the past decade, the locus of economic power in the world has been shifting away from the U.S. and Western Europe to the rising nations and metros in Asia and Latin America. Given the rising demand abroad, U.S. metros must network globally to broaden the possibilities of trade and exchange, and cultivate sources of investment and talent. Metros will ally with a different mix of partners based on their distinctive clusters and assets.

Globalization theorist Saskia Sassen and others have done path-breaking work in drawing attention to and documenting many of these international webs. As Sassen notes, global cities “must inevitably engage each other in fulfilling their functions, as the new forms of growth in these cities party result from the proliferation of inter-urban networks.”

For example, metros with concentrations in financial services, like New York, are forming tight, interlocking networks for the continual transfer of knowledge, workers and capital with similarly focused metros around the world: London, Frankfurt, Paris, Shanghai, Tokyo, Sydney. Manufacturing supply chains tie Detroit to metros in both developed and rising nations: Monterrey, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Cologne, Johannesburg, Chennai, Chongqing, Hanoi. Systems of global freight transport are increasingly interconnected, moving goods seamlessly across land, air and sea and linking up key U.S. freight hubs such as Los Angeles and Chicago with similar hubs such as Tianjin, Seoul, Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai, Hamburg and Rotterdam.

These networks obviously start with firms that do business with each other, but over time they extend to supporting institutions — governments, universities, business associations — that provide support for companies at the leading edge of metropolitan economies. Eventually, these metros become less like fierce rivals, and more like a team with different specializations.

These metros, drawing on both their firms and supporting institutions, must build intentionally on these connections — not only as markets for their goods and services, but as sources of investment and talent.

One of the metros on the vanguard of broadening its global network is Seattle. The cities of Seattle, Tacoma, Bellevue and Everett, the Pierce and Snohomish county governments, the ports of Seattle, Tacoma and Everett, and the Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce have partnered to form the Trade Development Alliance of Greater Seattle to promote the region “as one of North America’s premier international gateways and commercial centers.”

The Trade Development Alliance promotes the Greater Seattle region in targeted world markets through publications, trade missions and benchmarking against other global cities. Bill Stafford, the organization’s former president, led trade missions for Seattle’s business and political leaders for the past 20 years to countries throughout Europe and Asia that are strategic trading partners for Greater Seattle and the state of Washington. These missions cement the personal relationships that are the foundation of business in many cultures. They not only have created export opportunities for Seattle-based firms, but have also helped attract direct foreign investment and even tourists. They are also a learning exercise for Seattle’s policymakers. According to Stafford, the Trade Development Alliance is helping Seattle “build the most internationally sophisticated leadership in the world.”

According to Benjamin Shobert, who runs a strategic consulting firm in Seattle, the Alliance’s trips lead to unexpected business opportunities. Describing a trip a few weeks ago, he said, “[W]hile my emphasis was on CleanTech, the exchange of ideas and networking has created two immediate opportunities to act on in an unrelated area. Taking the time to plug in and open yourself up to new opportunities is made easier and the opportunities broader through exchanges like this.”

4. Think Long-term, Act Near-term

Many city governments, economic development groups or chambers of commerce have a long-term vision, but successful metropolitan areas also have clear milestones on which they can act along the way.

Some of the most visible of these milestones are major international events. Turin, Italy, which was devastated by the rapid decline of the Fiat company, started to debate a groundbreaking strategic plan for its region in 1998. One year later, it was named the site of the 2006 Winter Olympic Games. The strategic plan and a prior 1995 urban master plan gained powerful urgency as Turin hastened to build the infrastructure to support the games and position itself as a center for tourism and sports. As one Turin Chamber of Commerce representative put it, the Olympics gave Turin a timeline to “leave behind our ‘habit of mediocrity’ that we’d had since the decline of Fiat.”

The city and surrounding region continued the momentum by hosting events like the International Architectural Congress in 2007, the designation as World Design Capital in 2008, and a celebration of the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy in 2011.

The point here is emphatically not that chasing high-profile events leads to a thriving metropolitan area. Rather, high-profile events can be powerful milestones to drive and mark metropolitan progress. A smart, realistic economic development strategy, based not on ribbon-cuttings but on real metrics, takes a lot of unglamorous work. Once the metrics are in place, the punctuation of big, feel-good undertakings helps keep people focused and committed to the larger plan.

5. Find leaders that reflect who you are now, not who you were 50 years ago.

Successful metropolitan leadership networks have become more diverse, inclusive and representative of a broad range of constituencies. This represents a stark departure from the period immediately following World War II, where civic organizations in most metros were led by a small group of elite business leaders from the dominant firms in the region. During this period, many of these business-led organizations had transformative influence on the political and economic landscape of their cities and broader regions, but power remained concentrated among a few corporate elites. But, as corporations consolidated and moved, and manufacturing began to decline, metro economies, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest, began to shift and diversify. As a result, as Hal Wolman and Royce Hanson have written, “the power and influence of these organizations began to wane after the mid-1970s, as economic restructuring, deregulation, and suburbanization took hold and demographic changes shifted political leadership.”

In some metros, this led to a broader and more diverse set of leaders, as heads of non-profit and philanthropic organizations, such as hospitals, universities and foundations, have become more involved and exerted greater influence. Because these institutions tend to be more diverse themselves, the networks that they join become more representative of the diversity of metropolitan economies than a small clique of corporate elites that dominated during the mid-20th century.

The experience of the Greater Cleveland metropolis during the last four decades is a mirror image of this general trend. After several decades of bitter disagreement between City Hall and corporate leadership, around 50 of Cleveland’s major chief executives with strong ties to the region banded together to form an organization called Cleveland Tomorrow in the early 1980s, with the goal of spurring job creation and fostering economic growth in the region. During the next two decades, Cleveland Tomorrow focused on improving education, increasing funding for research and development, attracting new businesses to the region and strengthening the position of existing Cleveland firms in the globalizing economy. While the organization was successful in helping to attract investment in Cleveland’s downtown core and broaden the base of economic assets in the region, Cleveland Tomorrow continued to be adversely impacted as corporations — and thus their CEOs — moved out of Cleveland or consolidated with other firms outside the region.

The outcome, as Wolman and others found, was that “professional service firms and non-profit organizations, particularly hospitals and universities, became more important to both the regional economy and civic leadership.” The growing influence of leaders from this more diverse set of organizations led to the merging of Cleveland Tomorrow with two other regional business groups in 2004 to form the Greater Cleveland Partnership. Not only did the Greater Cleveland Partnership encompass a wider range of organizations, it also expanded the geographic range of the organization to include the Akron, Canton and Youngstown metropolitan areas in Northeast Ohio.

Today, the Greater Cleveland Partnership is part of an even larger regional network, which also includes non-profits like the Fund for Our Economic Future and other alliances of mayors and regional stakeholders. These regional organizations are critical to the long-term health and prosperity of Northeast Ohio, and in fact are starting to work on long-term competitiveness strategy for the region.

The new frontier in metropolitan networks is social networks, or the new technologies and platforms that connect people instantly and expansively. Mayor Cory Booker of Newark, N.J., for instance, has 1.1 million Twitter followers — more than four times the number of people who live in Newark.

In May 2011, the city of Philadelphia started a campaign to facilitate the safe co-existence of walkers, bicyclists and drivers on the city’s streets and sidewalks. Police officers gave warnings or citations to drivers and cyclists who had moving violations, and reminders to pedestrians who were too focused on their smartphones to pay attention to traffic. In July, the local CBS outlet mistakenly reported that anyone texting while walking would be ticketed and fined.

This is exactly the kind of “you must be kidding” idea that would go viral, and it did, appearing first in Gawker and eventually in several other outlets including Time magazine’s Techland column.

But the advantage of social media is that the city could respond to the misperception almost as quickly as it spread originally. Mayor Michael Nutter, who had been on Twitter for about nine months at that point, quickly tweeted, “It is NOT illegal to text and walk in Philly. You will NOT be fined. You will NOT be ticketed.”

Texting while walking is hardly an earthshaking public policy matter, but as mayors take on more complicated or emotional issues, from public sector pensions to property taxes, social networking tools can help them make their policies better understood. People still may disagree with mayors’ decisions, but at least they are disagreeing with an actual policy, not a rumor.

In Newark, N.J., advisors to Booker are excited about the way that social media seems be amplifying citizens’ sense of empowerment (the word comes up repeatedly in conversations with Matt Klapper, Booker’s senior policy advisor, and Matt Donnally, who advises Booker’s campaign on social media.) “There is a spillover effect of engagement,” says Klapper. “Bringing government closer can really have a profound effect.” For Booker, Twitter’s long arm helps with outreach programs, including an interactive public health and fitness campaign.

“Even the wisest of crowds cannot grapple with complex policies in 140 characters.”

Perhaps most critically, the people reached by social media often belong to groups government has long struggled to touch. A report by the 2010 Pew Internet & American Life Project found that while social media engages broad and diverse constituencies, blacks and English-speaking Latinos are more likely than whites to use social networking sites, and are more likely to check those sites daily. Blacks and Latinos were also much more likely than whites to say that government outreach via social media “helps people be more informed about what government is doing,” “makes government more accessible,” and that it is “very important” for government agencies to use social networking sites to share alerts and information.

The promise of social media is that eventually, metropolitan leaders can quickly assimilate the best ideas from other places and even use these diffuse social networks to crowd source solutions to difficult problems. We are not there yet — even the wisest of crowds cannot grapple with complex policies in 140 characters. But today’s tweets may be laying the groundwork for something bigger. Both Twitter and Facebook have units devoted exclusively to getting public officials to use their social media tools. These groups may devise the next breakthrough technology for a more thoughtful public debate. Booker’s team is experimenting with Quora because, as Donnally says, “it’s important to maintain a multi-platform social media strategy so you’re in a position to take advantage of changing trends and different communities to maximize your reach.”

There are ample reasons to be bullish about the trajectory of metropolitan networks in the United States. Competition, innovation and replication are powerful traits, and ones that can thrive in today’s digital age.

Metro collaboration is its own “idea virus,” tailor-made for replication. At a time of federal drift and dysfunction, these innovations send strong signals to metropolitan communities eager to grow, retool their economies and make the prerequisite transformative investments. The next decade will see a proliferation of new, enhanced metropolitan institutions and networks — as a result, new strategies and interventions on everything from transport to energy to competitiveness.

“Who you know determines who you are.” Reid Hoffman’s dictum is an imperative for metropolitan leaders. They have to know others across municipal borders and even global frontiers, across different economic sectors and social groups. They have to know their constituents, and be open to ideas coming to them from new technologies and new voices. That kind of networked and ever-evolving knowledge determines whether or not metro leaders — and the places they are building — will flourish in the coming age.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Bruce is the inaugural centennial scholar at the Brookings Institution and the co-author of The New Localism and The Metropolitan Revolution. He regularly advises on policy reforms that advance the competitiveness of metropolitan areas. Katz is a member of the Next City Board of Directors, a graduate of Brown University and Yale Law School and a visiting professor at the London School of Economics.

Jennifer Bradley is the founding director of the Center for Urban Innovation at the Aspen Institute. The Center's mission is to connect innovation and inclusion in cities, so that all residents benefit from new processes and technologies. She is a co-author of The Metropolitan Revolution, with Bruce Katz. Before starting the Center for Innovation, Jennifer was a Fellow at the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program. She has also worked as a lawyer and a journalist. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Eleanor loves animals: You name it, she’s probably drawn it. Eleanor’s unique graphic perspective aims to simplify lines and playfully arrange form to capture the essence of each animal she draws. She’s well known for her graphic take on our feathered, furry and fuzzy friends, and her illustration career has grown from its rock poster roots with jobs for clients such as Keds, Giro, Urban Outfitters and Wilco.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine