Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEvelyn Poor is part of the growing population of urban revivalists. She frequents gyms, coffee shops and yoga studios within walking distance of her recently retrofitted condominium in Center City Philadelphia. She’s fashionable, sporting a ruffled pink polka dot bathing suit, even in frigid February. She brunches. And she’s nine months old.

But that’s precisely what makes her so cutting edge. Evelyn is an urban baby, and her parents, Katie and Alex, are exactly the kind of people helping to repopulate the city. The two met when they were co-captains of their medical school soccer team, competing in the Philadelphia Professional Schools league, which pitted medical residents from Thomas Jefferson University against footballers from Wharton, the University of Pennsylvania’s business school.

Both now done with med school and balancing doctoring with parenting, Katie and Alex live in a condo they bought on Race Street, steps from Hahnemann University Hospital where Alex is completing his surgical residency. In June, when Katie went into labor with Evelyn, she and Alex walked down the street at 2am to Hahnemann’s 17-room post-partum obstetrics wing.

From the decision to buy a home downtown to a weekend brunch routine, the young family’s experience represents a trend that Philadelphia and other cities like it are banking on. Urban America has seen a boom among these young professional families, many of whom, like the Poors, grew up in the suburbs and want a different lifestyle than their parents. Tens of thousands of young adults between the ages of 20 and 34 have made homes in Philadelphia over the past seven years, making them the city’s fastest growing demographic by far. In 2006 this group made up only slightly more than one-fifth of the city. In 2011, it accounted for more than a quarter, according to a March report by Pew Charitable Trusts.

With the population explosion have come businesses catering to these young educated types — trendy whiskey and wine bars, shops selling organic baby onesies, countless ramen noodle bars. In 2011, a former strip club became Nest, a members-only club for the mommy-and-me yoga set offering a place for parents to mingle over a latte and watch their kids play or take classes. Burgeoning with restaurants, schools and services, it’s a long way from the Center City of the 1980s and the 1990s, when businesses shuttered precisely at 5pm and people worried about violence and drugs, not long waits for brunch.

That was the city that Krystalie Ocasio grew up in and, in many ways, still experiences. Like Katie Poor, she gave birth at Hahnemann last year. Unlike Poor, she could not walk there. An uncle drove her to the hospital from her home, five miles away in North Philadelphia.

The slim 17-year-old grew up in a house on Allegheny, one of the larger, busier avenues running through North Philly. Her parents split when she was young and she mostly lived with her grandparents. But the family was tight-knit. Ocasio was active in her Pentecostal church, even taking a missionary trip to Honduras. “Growing up, they were always protective,” she remembered. “I was always in the house, not on the street.”

But around when she turned 14 she said she started to “get into all that crazy stuff,” fighting with her friends, smoking marijuana and dating her current boyfriend, who is six years her senior. Last year, she became pregnant with his child.

It came as a surprise. Ocasio had recently had a cyst removed from her ovary. The ordeal, she thought, made pregnancy unlikely. She learned differently at the hospital when she went complaining of stomach pain that she figured was another cyst. There, with her grandmother in tow, she was confronted with a positive pregnancy test.

Teen pregnancy is on the decline in the U.S. The latest statistics for 2011 show the national teen birth rate at its lowest point in 30 years, with 31.3 births per 1,000 teens between the ages of 15 and 19. Black and Hispanic teenagers, however, have much higher birth rates: 47.4 and 49.4, respectively. Philadelphia has an even higher concentration of pregnant adolescents, with a teen birth rate of 63 in 2012. Policymakers and advocates of various stripes have clashed over how to treat teens that choose to have children, with some saying that these mothers should not be shamed by their decision or made to feel like it was the wrong thing to do. Yet despite the disagreements, research shows that people under the age of 18 who have children face a harder time than their peers. They have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, and only around half of teen mothers earn a high school diploma by age 22, compared to 90 percent of women overall.

Already, motherhood has been a transition for Ocasio, more so than she had anticipated.

“I don’t regret my son because I love him so much,” she said, “but I wish I could have waited.”

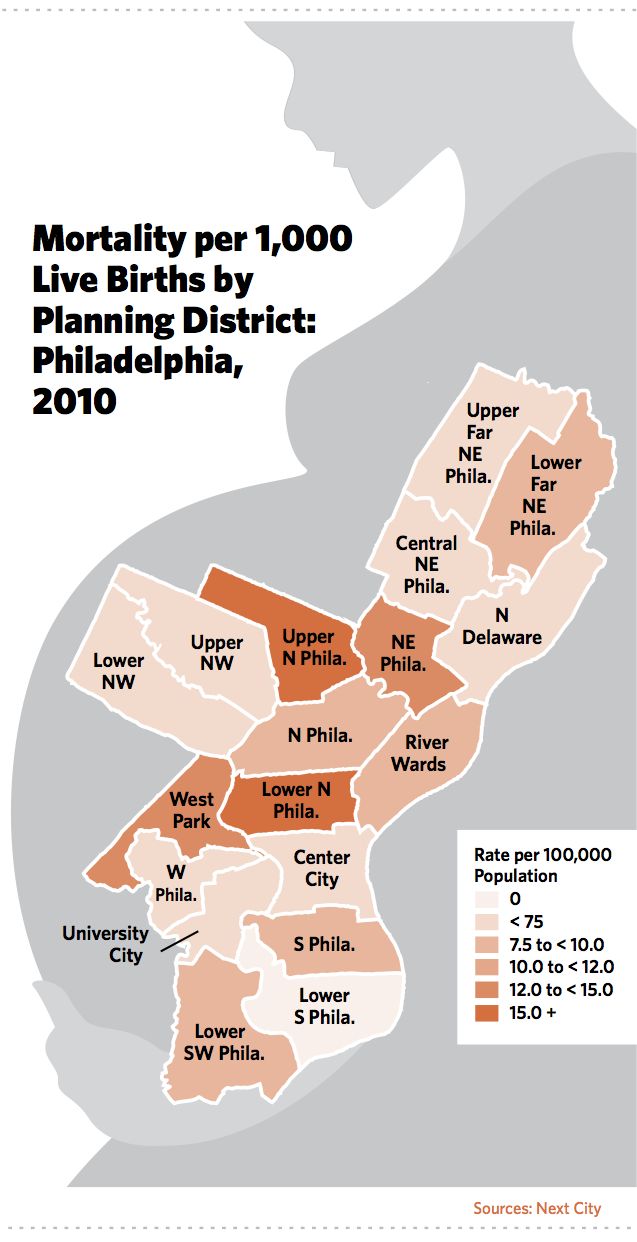

The connection between socioeconomics and infant health is significant enough that when maternal health statistics are aggregated onto maps and color-coded, the poorer sections of most cities are wholly different colors than wealthier sections.

Poor and Ocasio represent two parts of a story that will determine Philadelphia’s future. They are both mothers, devoted to their children and learning as they go. But the wide differences in their experiences point to the deep inequalities coexisting in American cities today. From pregnancy to school choices, these women confront vastly different challenges. The contrasting challenges they face serves as a wakeup call for cities about the depth and breadth of inequality that manifests even in the most basic, and shared, human experience of birth.

As Philadelphia transforms, there is a distinct possibility for social gaps to widen, and for the growth to exclude the city’s poor. For the first time in decades, more people are moving to the city than leaving it, and many of the newcomers are better educated or wealthier than the average Philadelphian. But alongside the rehabbed brownstones and loft-style condos, hundreds of thousands of families continue to live in poverty, giving Philly the dubious distinction of having the largest population living in poverty of any major city — 25.6 percent. In the region, that compares to 18.2 percent in Washington, D.C., 19.4 percent in New York, 21.4 percent in Boston and 22.4 percent in Baltimore. And while the numbers vary, the same challenge crops up in all of these fast-gentrifying cities: How to ensure that growth happens without leaving the most vulnerable populations behind?

Among those vulnerable populations are children born into low-income families. Research shows that low-income women are more likely than their wealthier counterparts to birth underweight or preterm babies, conditions that come with health risks. The connection between socioeconomics and infant health is significant enough that when maternal health statistics are aggregated onto maps and color-coded, the poorer sections of most cities are wholly different colors than wealthier sections. In Philadelphia, for instance, higher rates of preterm births and low birth weight concentrate in the city’s poorer southwest, west and northern sections, according to a 2010 report issued by the city’s Department of Public Health. North Philadelphia had the highest rate of infant mortality, the report showed. The lowest rates of infant mortality, low birth weight and premature birth were in the city’s central district, an unshaded area on the map encompassing gentrified neighborhoods in and around Center City.

These patterns are not accidents of geography. Rather, they demonstrate the literal life-or-death consequences of being born into urban poverty today — even in a city undergoing a tremendous renaissance.

Poor and Ocasio’s divergent daily lives converged in the hospital. Poor chose to birth at Hahnemann because of her insurance and its location down the block. Ocasio ended up at Hahnemann because she knew she didn’t want to go to Temple, the maternity ward closest to her home in North Philly.

“I just heard people say they don’t treat them right or they didn’t have a good experience,” she said, “so I just didn’t want to go over there.”

The birthing commute was also the result of more than a decade of hospital spending cuts. In 1997, Philadelphia had 19 maternity wards in the city. Now there are six. Most are located miles from the neighborhoods with the highest birth rates, and all are associated with a medical school.

Temple and Einstein are the only remaining maternity wards in North Philadelphia. (By contrast, there are three in Center City, though less than 10 percent of the city’s births between 2000 and 2010 took place in the district.) Together, the two North Philly wards served 6,500 patients in 2011. A sizable number of those women had no previous contact with the institutions, because ambulances bring women to the closest hospital, not the hospital where she planned to deliver, and Temple pulls in women from vast areas in North Philly. When a woman’s first encounter with a hospital is her delivery, the staff at her birth knows nothing about risk factors like diabetes or hypertension, or what kind of prenatal care she received.

Dr. Jack Ludmir chairs the obstetrics and gynecology department at Pennsylvania Hospital in Center City Philadelphia. He speaks softly but with conviction about his commitment to providing care to Philadelphia’s neediest mothers. In addition to his duties at Pennsy, as the hospital is nicknamed, he started a program to provide prenatal care to undocumented and uninsured mothers and co-founded the Philadelphia non-profit Puentes de Salud, which provides health care to Latino immigrants regardless of their immigration status. On the side he also was chair of the section for Maternal and Child Health at the American Hospital Association in 2011.

In his office, upstairs from the gleaming antique tile floors of the country’s first hospital, he shows a map of the city’s obstetric wards. He points to the areas that have lost OB services in the past 15 years — North Philly, West Philly, South Philly, all neighborhoods with higher poverty rates. “When you see this,” he said, “you say ‘oh my god, where are women going?’”

It’s not hard to understand why Philadelphia has fewer maternity wings now than it did 10 years ago. Delivering babies is a costly business in the U.S., and especially in cities disproportionally populated by uninsured or high-risk populations. An average uncomplicated vaginal birth cost around $10,000 in 2010, while a complicated cesarean averaged more than $23,000, according to Childbirth Connection, a century-old non-profit focused on maternity issues. Public insurance doesn’t cover all the costs and in Pennsylvania, the difference is especially significant. Here, the overall reimbursement from Medical Assistance, the state version of Medicaid, is 80 cents to the dollar. That means big losses for Philadelphia, where two-thirds of births are to women on Medical Assistance.

“The more Medical Assistance patients that you are caring for, the more money you’re going to lose,” explained Priscilla Koutsouradis, communications director at the Delaware Valley Healthcare Council of the Hospital Association of Pennsylvania.

Ludmir was blunt about the problems urban maternity wards face. “If there wouldn’t be training programs… I don’t know what would happen to… those obstetric services. Hospitals would struggle how to provide obstetric care when it will just be losing money, losing money, losing money.”

The soaring rates of liability insurance, which according to the American Hospital Association have doubled since 2000, have also tipped the scales against obstetrics. “Issues of malpractice changed the landscape,” said Dr. Arnold Cohen, former chair of obstetrics at Einstein Medical Center in North Philadelphia and now the program director in OB at Einstein and professor of obstetrics at Jefferson Medical School

Cohen estimated that hospitals lose between $2,000 and $4,000 for every delivery. “All you need is one $50 or $100 million case, which happens not infrequently in Philadelphia, to wipe out all your profits,” he said, “and that’s why the hospitals closed.”

Yet cutting the money-draining maternity wards created unforeseen public health costs.

In the three years after the 1997 hospital closures, infant mortality rates in the city increased by nearly 50 percent, according to a study done by the Center for Outcomes Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Though the mortality rates gradually leveled off to the same rate as before the closures, pediatric researchers say the spike demonstrates the grave health risks posed by maternal service reduction. “Previous research on patient outcomes after hospital closure have focused on the impact of closing rural hospitals or single hospitals in a large metropolitan area,” study leader Dr. Scott A. Lorch, a neonatologist and researcher, said in a release issued after the study was published. “Our study was the first to systematically analyze the effects of large-scale urban obstetric service reductions on the outcomes of mothers and babies.”

Pennsylvania has also seen its maternal mortality rate rise in the years since city’s maternity wards closed, rising from 9.7 per 100,000 live births in 2005 to 14.5 in 2010, though research has not linked the rise directly to the closures. The North Philadelphia neighborhoods of Olney and Port Richmond had among the highest levels of neo-natal mortality in the city in 2009, Philadelphia Department of Public Health records show.

In the case of Ocasio and Poor, both were lucky, delivering healthy babies and leaving the hospital themselves healthy, if exhausted.

“My delivery was great,” Poor recalled. “I ended up loving my OB who was there. I was concerned about being at a teaching hospital and having residents deliver the baby, just because I know what goes on, being in medicine.” The fears were unfounded, she said. She stayed four days at the hospital until she was sure she had healed enough from her C-section surgery to walk.

For Ocasio, the delivery of her son, Jesus, Jr., felt a little more tumultuous. She was allowed three family members in the room. Her boyfriend, an aunt who had been studying childbirth support and her grandmother came in first, which left her mother out in the waiting room.

Her aunt, Ruth Rodriguez, who had taken training to become a doula (a labor support person), was not happy with the treatment she saw Ocasio receive. “I felt bad for my niece because even though I did everything I could, she wasn’t being treated respectfully,” Rodriquez said. “The nurses kept saying, ‘those little girls don’t know anything.’”

In the five months since Jesus was born, Ocasio has learned a lot about the daily struggles of motherhood.

“I thought it was going to be easy because I would help take care of my baby cousin,” she said. “But he wasn’t mine, I could give him back.”

Ocasio was a 10th-grader at Thomas Alva Edison High School when she became pregnant. The North Philadelphia school is notorious for violence. In 2011 it graduated fewer students on time than any school in Philadelphia, with only 38 percent matriculating in four years, Department of Education data shows. “It’s bad,” Ocasio said. “Not as bad as you hear, but it’s bad.”

Her pregnancy wasn’t out of place in Edison’s classrooms. “There were so many pregnant girls,” Ocasio said. But still, she left the school before she started really showing.

This year, Ocasio started taking courses online so she can stay home with Jesus, Jr. A calm baby, he fusses only when hungry or wet, and sports fashionable baby wear passed down from his older cousins. Ocasio talks like the new mom she is, explaining how Jesus’ outfit fits him, even though it’s size six months, “because Children’s Place runs small.” She said his Air Jordan baby booties were just one in a collection of fashionable footwear gifted or handed down.

The police, she said, don’t make her feel safe despite their heavy presence. These concerns about safety have her planning to keep Jesus inside her home.

Ocasio and Jesus split their time between her grandparents’ home on Allegheny and the house her boyfriend’s father gave them to live with the baby in Kensington. Jesus Gillermo Oyola is a doting father — in a brief visit he honed in on the infant, smothering him with kisses and repeating, “this is my baby, I’m crazy for him, if I’m not around him I stress about him.” But already there’s pressure in the relationship. “We try to keep it together for the baby,” Ocasio said.

Her boyfriend, now 22, has never had a job during their relationship. He used to receive Social Security, but that recently got cut. With their 3-month-old to feed, Ocasio has been trying to add employment to her mounting list of responsibilities. “I applied for so many jobs, I don’t even know who else to apply to.” She got called back for one interview, but later found out she didn’t get the position.

For now she’s scraping by with help from her family, eating easy-to-prepare instant foods she can pick up on the cheap at the corner store, or meals home cooked by her grandma. “My grandmother’s the one that helps me out,” she said.

Ocasio’s daily concerns look very different than the ones borne by the Poors across town.

For Katie Poor, motherhood is a balancing act between years of training, residencies and work, but one that is going smoothly. The couple planned to have its first child when she finished her fellowship, before starting work. “It was ridiculous how well it turned out,” she said. Evelyn was born on the day of her graduation, so she missed the ceremony. Within two months she had started working part time.

Still, keeping everything going has been tough, especially with Alex’s grueling schedule at the hospital. “I have so much respect for single moms,” Katie said as she remembered when Alex had a residency in New Jersey and would spend days away from home. But Evelyn is a positive and calm baby and Katie loves parenting, especially in the city. Her “get out of the house” routine includes walking Evelyn to the recently renovated Sister Cities Park at the edge of the parkway and strolling with her around the city.

“She’s probably been out to brunch more than my husband,” Katie said laughingly. “We’ve got the Bjorn, I have the Moby wrap, we have strollers, we have so many ways to wrap the baby up and get her out. Taking her outside and walking around everyday was a big part of my recovery.”

From Poor’s perspective, Philadelphia is becoming more and more pedestrian-friendly, and she thinks where she lives may be the most walkable part of the city. The park has fountains for kids to play in and a modern café. Logan Circle is nearby and Whole Foods, where she buys organic baby food for Evelyn, is just a few blocks down the green parkway.

Like Ocasio, the Poors depend on family support. When Katie first went back to work part time, Evelyn’s two grandmothers would babysit, sending photos throughout the day. Now Evelyn goes to the Friends Child Care Center, a Quaker daycare a block away from her home. The Poors signed up as soon as Katie got pregnant. Getting a space was no problem.

The increasing number of middle-class professionals choosing to raise families in Philadelphia has not gone unnoticed. Center City District, an influential public-private partnership supporting downtown economic development, created Kids in Center City. The online portal helps parents learn about school and kid-friendly entertainment options in the city. And for the first time, the Greater Center City area has a neighborhood schools coalition uniting parents in support of schools in the district. Christine Carlson, who founded the coalition, has a 9-year-old daughter at Greenfield Elementary School in the Rittenhouse Square neighborhood. She was one of 12 kids who lived in the catchment area, while the rest came from other parts of the city. This year, Carlson said, the principal told her there would no spots for children from outside the catchment area, as local kids are now staying in the city and attending the school.

The very existence of Nest, the membership-only baby boho clubhouse, speaks to the awareness of the influx. Three couples, all six members of which grew up in Philadelphia’s suburbs, created and co-run the space. “We are all city girls,” explained Raina Gorman, one of the owners. “We love, love, love, love the city.”

“It’s unbelievable how many families are staying in the city and raising their kids at least until school age,” Gorman added. “There was such a demand for this kind of a place, way more than there would have been five years ago.”

“She’s probably been out to brunch more than my husband,” Katie said laughingly.

On Valentine’s Day the three-story children’s wonderland bustled with activity. On a top floor, Philly celebrity chef Marc Vetri taught toddlers to cook macaroni and cheese. A handpicked girl group played songs ranging from “Kiss Me” to “Yellow Submarine,” with some classic kids jams like “The Wheels on the Bus” thrown in. Kids and parents munched on gluten-free sandwiches (goat-brie with fig spread, smoked salmon, black bean hummus) catered by the fashionably local, organic, vegan-friendly Rittenhouse café Pure Fare. Downstairs kids decorated cupcakes catered by Three Cat Kitchen and played in a colorful playroom.

As Gorman and her business partner Hara Caplan told the Nest story, Gorman’s daughter Marlo wandered upstairs. Her mother was unperturbed. ”That’s just how safe I feel,” she said.

Ocasio has never been to Nest. For her, finding a safe place to play with her son is a battle she’s almost given up. Directly across from her house, a massive boarded- up building towers next to a vacant lot. Streets are strewn with garbage and public trash cans are rare. Walking from the train to her house on a recent visit, I passed a loud, violent spat between a man and a woman standing on a corner outside an elementary school. Against a mosaic mural that declares “none of us can do alone what all of us can do together,” the man grabbed at the woman, tugging her down as she fell to the ground and tried to slither out of his grip, screaming all the while. Security from the school tried to break them up. The neighborhood came to a standstill as people stopped and stared from the three opposite corners. Two ambulances, unrelated, wailed past the scene.

Within the chaos of her neighborhood, Ocasio’s house is cozy, crammed to the brim with baby gear, clothes, photos, chairs and boxes. She tries to stay inside as much as possible. “There are so many drugs in this area, that makes everything worse,” she said. “Walking up the block someone under the influence can hurt your kid.”

I asked her if we could take a stroll to a nearby playground. Navigating into the run-down park, past graffiti-covered signs, the wheels of her stroller got caught in a broken Snapple bottle. “That’s why I don’t come here anymore,” she said, looking down.

Ocasio blamed the deterioration of the neighborhood on joblessness. “There’s really no jobs available now,” she said. “That’s why kids are standing on the corner.” She shook her head at the situation. The police, she said, don’t make her feel safe despite their heavy presence. These concerns about safety have her planning to keep Jesus inside her home, in the care of family and off the street as much as possible. She said he could socialize with cousins. When he gets older, she plans to have him homeschooled. “After everything that’s been going on, I do not want him in a school,” she said. “I do not want him getting hurt.”

Even in the face of shrinking birth choices, Philadelphia is home to an active community of passionate reproductive health activists, those who believe that birth can be an empowering and transformative moment in a woman’s life if it takes place in the right environment.

Naima Black, a program coordinator at the Maternity Care Coalition, a citywide maternal health organization, learned much about birth while living in a small village in Lamu, Kenya, where she assisted and attended many community births. Now she is working in North Philadelphia training local women to be doulas, like Ocasio’s aunt. She also works directly with clients supporting them through their labors and after in the transition to motherhood and breastfeeding.

“I think it’s very empowering… when a women has the intent and succeeds at birthing her baby and knowing that she is the only one who can feed [and] nourish her baby,” she said. “It’s a reclaiming of our power in birth and infant care that’s really integral for me.”

Doulas are not medical staff, but are present to emotionally and physically support a mother during her delivery. In Philadelphia they often work within the hospital context, though they can also assist with home births or at a birth center.

There is no birth center in Philadelphia, something Vivian Lowenstein, a certified nurse midwife and longtime member of the local birth advocacy community, bemoans.

“Birth should be in the community,” said Lowenstein, president of WomenCare, an organization that hopes to build a birth center in Northeast Philadelphia. “If a woman lives in the community, she should be able to birth in that community. She shouldn’t have to travel 30-40 minutes or go into another community or go into a big tertiary hospital.”

Birth centers are places where women with low-risk pregnancies can deliver in a more soothing environment and without the medical interventions common in hospitals. Lowenstein worked at the Booth Maternity Center, later renamed the Franklin Maternity Hospital in the 1980s until it closed for financial reasons in 1989. It was a well-loved institution that supported natural childbirth. She maintains fierce loyalty to the center’s ideals of placing a woman at the center of her birth, and has fond memories for the place she recalled as “the best kept secret in Philadelphia.” Now she is hoping to build it again, if only she can find a major donor to kick it off.

The closest birth center to Philadelphia is in Bryn Mawr and exists in partnership with Montgomery Hospital. There, women birth in suites equipped with Jacuzzis and attended by midwives. Around 1 percent of births in the U.S. happen outside of hospitals, and of those the majority are home births, with birth centers making up less than a third. It is generally the upper echelon of society that has access to birth centers.

Julie Cristol, a nurse midwife at the Bryn Mawr birth center who has worked with underprivileged mothers throughout her career, acknowledged the lack of diversity. “We are about 15 percent Medicaid or so, mostly because of the location being in Bryn Mawr… since I’ve always served uninsured and underinsured women it’s kind of weird for me to be serving women who are incredibly well educated and can get excellent care even without me to serve them.”

Cristol called it unrealistic to open a birth center in the city, because partnering with a hospital is essential in case of an emergency. While the government covers the liability insurance for staff at federally qualified health centers and reimburses higher rates for Medicaid patients to offset the cost of providing for the uninsured, medical liability for any complicated cases would likely fall on the hospital where a woman transfers. Consequently there is little motivation for hospitals to invest in birth centers.

Cristol’s cynicism, when compared to Lowenstein’s optimism, may stem from their different experiences. Lowenstein has been working at a federally qualified health center and has seen the potential to expand the system to cover low-risk births. Cristol, on the other hand, used to work at a birth center attached to Pennsylvania Hospital, which eventually was shut down after years of struggle and financial pressure.

But both bemoan the breakdown in continuity of care in the city. Lowenstein reminisced for the homey birth environment of the Franklin Maternity Hospital, and Cristol recalled working as a midwife in the early ’90s, when hospitals actually paid for ambulances to bring women to their delivery rooms, women were better matched with services, and it was easier for staff to know the women they were working with. Now, she said, “continuity means getting to the hospital where your chart is, and that’s about it.”

Owen Montgomery, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Drexel, which partners with Hahnemann hospital, agrees that continuity of care is a major issue.

“Typically women have prenatal care and they go to the hospital and no one knows them,” he said. “That’s a broken part of the service.”

The city and the hospitals are trying to address that by putting in communal electronic medical records, but so far the project has not moved forward.

Ocasio said that there should be “closer hospitals that deliver besides Temple, because not everyone wants to go there.” But she’s not expecting any change. Looking toward the future, I asked if she thought there was something the government could do to make mothering easier in her neighborhood. “I think there’s nothing the government can do. It’s too late.”

Or is it?

In the years since Philadelphia’s infant mortality rate spiked in the late 1990s, the number of deaths has leveled off. Lorch, from the Children’s Hospital, said the improvement is tied to new collaborative efforts on the part of players in the city’s maternal health community. “After about 1999, the city of Philadelphia starting taking a lot of notice,” he said. Closures became less abrupt as the city monitored which hospitals would close and tried to facilitate the smooth transfer of women to other hospitals.

The number of deliveries at Einstein more than doubled, from 1,441 between 1996 and 1997 to 3,073 between 2010 and 2011. Temple jumped from 1,651 in the 1990s to 3,473 between 2010 and 2011. Pennsylvania Hospital has the most births at 4,842, up from 3,946.

While some of the wards have expanded, and many have adjusted practices to mitigate all the births, Montgomery said many of the hospitals are running at 80-90 percent capacity on any given day. This is problematic, because obstetrics fluctuate.

“We don’t predict when babies come,” Montgomery said, “so when you have a surge like a hurricane, full moon or nine months from the New York City blackout, you don’t have enough beds.” He added while wards are recommended to run at 75 percent capacity, the wards in Philadelphia run around 80-90 percent and can surge to 120 percent capacity, requiring creative use of space or borrowing of other floors.

The impact, he said, is obvious. “It’s not really rocket science to think if you’re overcrowded and don’t have enough beds and have too many people that need the C-section room at same time, near-misses may occur or someone may have a delay in care.”

The packed maternity wards have confronted the problem with regular monthly meetings between the heads of all of the surviving obstetric wards in the city. They discuss challenges and collaborate to address the issues women and hospitals face.

The doctors describe the meetings, started around five years ago, as an organic outgrowth of passionate participants in a rapidly shrinking field. Cohen, of Einstein Medical Center, who has been in the maternity field in Philadelphia for decades, said the group formed out of long-term relationships — three of the current chairmen were residents under him. And he argued that this has led to improvement.

“I know [mothers] are getting better care,” he said. “There’s no competition anymore. We’ve taken the competition out of obstetric care. It’s not like I care how many deliveries they do or they care how many deliveries I do, because we all have enough deliveries to do.”

At a recent meeting, the heads of the maternity wards sat around a communal table at the Drexel Medical Education building. They munched on sandwiches, chips and cookies from the Corner Bakery. Most sipped diet coke, leaving the full-calorie Sprite and Coke cans untouched. Ceiling-length bookshelves lined the walls, crammed with old publications from the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, interspersed with black and white portraits of brand new babies.

The air was convivial among the doctors, even as they sparred — not so genially — with a guest participant from one of the major insurance companies. After a short presentation about implementing more community health workers into their clinics, the doctors traded news and tips.

Several of Philadelphia’s chairs serve on national boards, and they say the communal approach to maternal care is unique in the country. Lorch said the collaborative response, evidenced by the close relationships between the OB/GYNs in the meeting, is part of why the infant mortality rates have stabilized.

In fact, stakeholders from across the spectrum seem a bit torn as to the overall impact of the closures. On the one hand, all of the births in Philadelphia hospitals now take place at advanced level-three tertiary care centers, so anywhere a baby is born has access to excellent emergency and newborn care. There are no transfers from community hospitals to higher-level centers because all the remaining centers are high level.

But it means moms like Ocasio have nowhere to birth in their neighborhoods, and there is a substantial disconnect between women and their providers — especially for women in distant, underserved parts of the city where they access prenatal care in clinics and head to a strange hospital for the first or second time for their delivery.

As Cristol said, “The big hospitals are working together much, much more than they used to. There’s a big effort to make care more evidence based… the quality of care is good.” But, she said, “The quality of the experience absolutely sucks. There’s no continuity, everybody is busy, the staff is grouchy.”

Evidence is growing about the impact of chronic stress on the outcomes of babies. It’s become ever more clear that parents trying to navigate distant health systems as well as tumultuous neighborhoods are passing physical negative implications of that stress onto their children.

And as much as the hospitals try to adapt to a shifting and growing population of birthing mothers, they are doing so from their brick-and-mortar locations hugging the city center. While Montgomery insisted that there is a single standard for care within the hospitals, access to those hospitals is as divided as the city. And the mothers who travel farthest for care are the mothers that simultaneously face deep poverty, unemployment, poor schools and violence.

Joan Bloch, a nurse and public health researcher, sees the situation as completely ostracizing mothers in certain neighborhoods. “The odds are stacked against them,” she said.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Allyn Gaestel is currently a Philadelphia Fellow for Next City. Much of her work centers on human rights, inequality and gender. She has worked in Haiti, India, Nepal, Mali, Senegal, Democratic Republic of Congo and the Bahamas for outlets including the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Los Angeles Times, Reuters, CNN and Al Jazeera. She tweets @allyngaestel.

Allison Shelley is an independent documentary photographer. She is a former staff photographer for the Washington Times, director of photography for Education Week newspaper, and is now co-director of the 250-member non-profit Women Photojournalists of Washington. She is currently working on a long term multi-platform project focusing on teenage maternal mortality worldwide.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine