Finding a job isn’t easy, especially in today’s crowded labor market. Now, bad credit is precluding many households from finding work. In August CNN Money ran a buzzed-about story on highly experienced workers who couldn’t find jobs because of credit blemishes. The problem is so common these days that Business Insider recommends running a credit check on yourself before looking for a job.

But it’s not just anecdotal. A February report from Demos, a New York-based policy and advocacy organization, found that widespread use of credit checks during hiring has fueled the country’s joblessness. Debts racked up during the recession have made it harder for many families to rebound because of what some consider discriminating hiring processes.

Demos interviewed more than 1,000 low- and middle-income households last year who had been carrying credit card debt for three months or longer. “Among job applicants with blemished credit histories, 1 in 7 has been advised that they were not being hired because of their credit,” Amy Straub, the study’s author, wrote. One in 10 unemployed survey respondents said they had been informed they wouldn’t land a job because of something on their credit report.

Employment credit checks are legal under federal law, so hiring managers aren’t doing anything criminal. (Though the 1970 Fair Credit Reporting Act requires prospective employers to inform candidates if their credit history was taken into account during the decision making-process.) But that doesn’t make it any less frustrating or contentious.

“I’m not sure why an employer would want to do a credit check,” said Christian Weller, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. “It’s unclear what the overarching logic is. I’ve been in this situation ever since I was in grad school 20 years ago. I’ve had to hire at people at every level of an organization, from interns to senior professors at universities. It never occurred to me, as a recruiter, to think about a credit check for any of these positions. I just want to know how good people are at their jobs.”

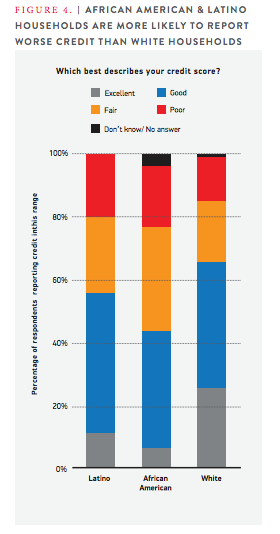

More importantly, minorities are disproportionately more likely to report poor credit, according to the Demos report. Which is a huge problem in cities, which tend to have concentrated levels of poverty and pockets of low- and middle-income minorities struggling to find work. Weller fears that it’s a nasty cycle only perpetuated by invasive credit checks.

“Credit checks create a vicious cycle — with an inequitable outcome — between being stuck in unstable, low-wage jobs and not having enough assets while having constantly to borrow at high-cost and high-risk debt,” he said. “It creates a feedback loop because these communities of color are saddled with that high-risk debt I mentioned, which then feeds back into their job search if employers regularly check on credit for employment.”

The cynics here would argue that people with poor credit have put themselves in this situation. But not everyone was able to bounce back quickly from the recession, especially with a slow job market. Besides, what does someone’s credit have to do with their job skills? “It’s such a distraction in my view to talk about people’s personal finances. I want to know if a person is good enough at her job. Is she skilled?” Weller said. “I also think it’s an incredible invasion of people’s privacy.”

As of February, eight states — California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Oregon, Vermont and Washington — have passed legislation to stop the use of credit checks by hiring managers. Dozens of cities and states have introduced similar bills, according to Demos. And until more city and state governments follow suit, scores of down-on-their-luck Americans will end up shut out of jobs they’re qualified for.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.