We humans have a tendency to carve up our cities into “the [blank] part of town,” where [blank] might be any number of ethnic, racial or economic identifiers. But a new study of Jerusalem, based on hand-drawn maps and global positioning system data, suggests that segregation is a much more fluid and personal than we often assume.

Noam Shoval and Malka Greenberg Raanan are, respectively, a professor and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and their new study appears in the latest issue of the journal Cities. What Shoval and Raanan set out to understand was how our “mental maps” of city boundaries match up with how we interact with a given space. Where do we think we belong? Where do we actually spend our lives? Their findings challenge the dominant understanding of, as they write, “Jerusalem as a contested city, divided into three distinct spaces, serving three conflicting cultural groups.”

Research on segregation tends to focus on where people live, as in their actual homes. But such residence-based study undervalues the segregation that happens outside the home. Interactions that carry real social weight tend to happen when we’re working, shopping, playing sports or going for a meal. The push in the field is to figure out, then, how to track the way people experience space as they go about the often-mundane activities of their daily lives.

Shoval and Raanan’s study tracked 18 women, all between the ages of 19 and 30, university educated, single and native to Jerusalem. Six were secular Jews, six were ultra-Orthodox Jews and six were Palestinian Muslims. Participants were given both the time-space diaries traditionally used in studies like this, as well as a GPS tracker to wear as they went about their lives for a week. The devices recorded their locations in the city every 10 seconds.

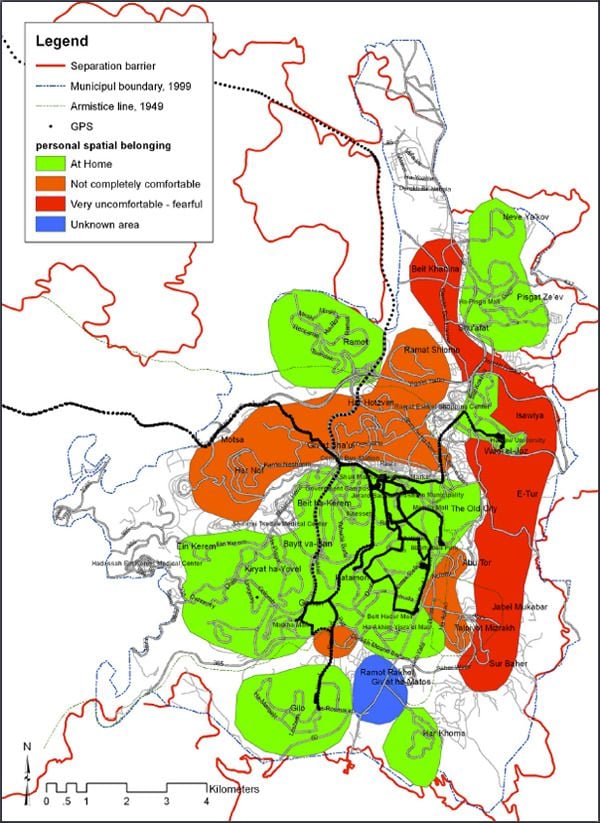

But before they began that real-time tracking, each of the women were asked to draw four maps: One identifying local landmarks to test their familiarity with the city, one carving up the city in any way the participant liked, one dividing it along secular Jewish/ultra-Orthodox Jewish and Palestinian Arab lines, and the last a color map — green meaning the places in Jerusalem they felt completely at home, orange where they felt somewhat less secure, red for the parts of the city they felt unwelcome or uncomfortable, gray for areas they didn’t feel strongly about, and blue for parts of the city they simply didn’t know.

(Sample digitized map based on hand-drawn boundaries.)

Once the GPS data came in at the end of the week, it was layered over digitized versions of the maps the women had drawn.

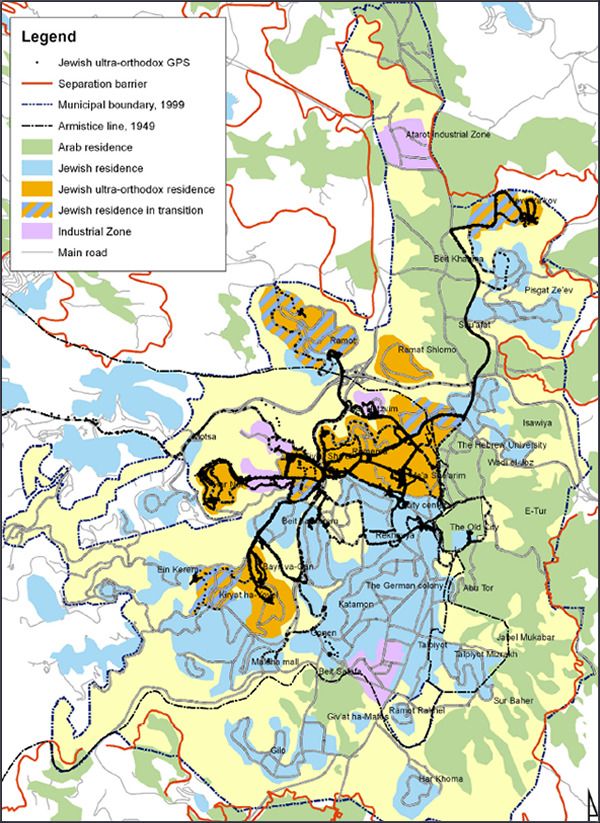

Jerusalem is often glossed as a city divided into three distinct areas. The Palestinian Arab population clusters in the eastern part of the city, the secular Jewish population in both western and eastern parts, and the ultra-Orthodox population in the north. Each area has its own social infrastructure, including shopping districts, schools and cultural institutions.

But the results suggest something more complicated than that. The women in the study didn’t always share the sense of place that they themselves attributed to their identity group. In fact 10 of the women, the authors write, “expressed a sense of personal belonging to territories which they did not perceive as belonging to their own cultural group territory.” Moreover, their mappings didn’t always show home zones as contiguous — there might exist an unknown region between two places where they felt at home.

(Map showing aggregate GPS data of ultra-Orthodox Jewish participants in the study.)

At first glance, the GPS data showed that the women stayed in sections of Jerusalem that they identified as friendly a considerable 94 percent of the time. “The participants,” the authors write, “hardly entered the territories which they perceived to belong to other cultural groups.” But things get more interesting when their residences are removed from the mix. Five of six secular Jewish women in the study still stuck completely to the parts of the city they associated with the secular Jewish population. But just one of the Palestinian Muslim women and two of the ultra-Orthodox women had their “personal territories” completely within the territories they identified as belonging to their cultural-ethnic groups. In fact, they were regularly pushed or pulled beyond those boundaries.

“Observing the activities of subjects outside of their homes emphasizes the asymmetry between the different cultural groups,” the authors write. “Ultra-orthodox Jews spent considerable time within the secular Jewish territory, whereas secular Jews hardly spent any time within the ultra-orthodox Jewish territories.”

When the Palestinian Muslim women did venture out of the area they associated with Palestinian Muslims, they tended to go into areas traditionally identified as secular Jewish, even though they defined the areas as not belonging to any one cultural group. Shoval and Raanan conclude that that was “mainly due to their lack of knowledge of the Jewish areas and their inability to distinguish between ultra-orthodox Jewish territories and secular Jewish territories.”

What emerges from both the women’s understanding of their city and how they engage with it is less a picture of a strictly divided Jerusalem, they write, than of “a city with a common central area in which the secular population tends to retreat, sided by two separate polarized territories where the ultra-orthodox Jewish community and the Palestinian-Arab community resides.”

Shoval and Raanan’s paper is part of a push to think about segregation on an individual level, with an awareness that it is, in practice, a more constantly negotiated construct than we might think. The study was small, they admit, but they suggest that it proves their methodology — marrying low-tech hand-drawn maps and high-tech geographic data — has merit.

If the method is replicated elsewhere, it will be interesting to see whether Jerusalem locals have, perhaps because of the city’s contested history, a more refined sense of place, or whether it’s something we’re all carrying around in our heads.

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.