In a bout of home-state devotion last month, the New York Times editorialized rather firmly against the hint of a proposal to cap the federal deduction for state and local taxes. The paper was upfront that New York, along with several other high-tax East Coast states, would lose big from any such cap.

The state and local tax deduction, the Times argued, is a subsidy from the federal government to states and cities that yes, taxes their citizens quite a bit, but does so in order to provide better services. Removing the deduction would force these states either to cut services or raise taxes themselves.

While this bit of reasoning is well accepted, not everyone agrees that the state and local deduction is such a blessing. James Kwak of The Baseline Scenario blog, for instance, notes that the deduction doesn’t affect all taxpayers equally:

It mainly benefits rich people because poor people tend not to itemize their deductions. (Their deductions aren’t big enough to be worth itemizing.) Since state taxes are not very progressive to begin with, this makes them even less progressive, or even regressive… In addition, rich towns get bigger subsidies than poor towns, simply because they have higher property values and hence people pay higher property taxes. If Greenwich, Conn. needs more money for its schools, it can increase property taxes. Residents might grumble, but they know that for every $2 they pay, the federal government is kicking in $1. In Hartford, Conn., not so much.

But it turns out that the story of the state and local tax deduction is quite a bit more complicated than either the Times or Kwak imply.

First, while everyone agrees that the deduction amounts to a subsidy from the federal government to states and cities, no one really agrees on why it exists.

In essence, one side argues that state and local taxpayers shouldn’t receive a tax break on income that they use to “pay” for local public goods — such as roads, health services and education — any more than they should receive a tax break for any other good they purchase. The other side argues that state and local taxes don’t equal the benefits for individual taxpayers: Some taxpayers pay more and receive less, others pay less and receive more. (This is the frightening phenomenon known as “redistribution.”) Under this view, deductibility makes sense because state and local taxes reduce a taxpayer’s ability to consume.

But beyond arguing about the motivation for tax deductibility, it isn’t entirely clear that the state and local tax deduction is strictly pro-rich, as Kwak implies.

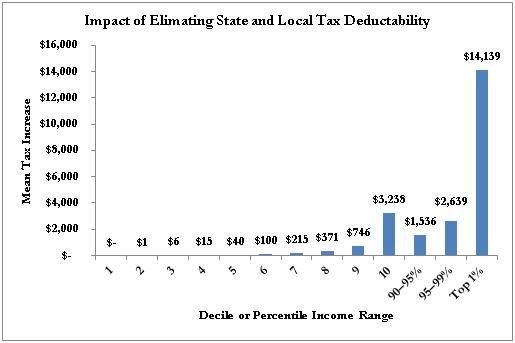

No one disagrees that the deduction’s impact on federal taxes is regressive: The wealthy benefit more from the deduction because they are more likely to itemize their taxes and because a higher income makes the deduction worth more. The effect of removing the deduction, shown in the chart below, makes this abundantly clear: The top 1 percent of income earners would see a mean tax increase of more than $14,000.

Source: Adapted from Metcalf

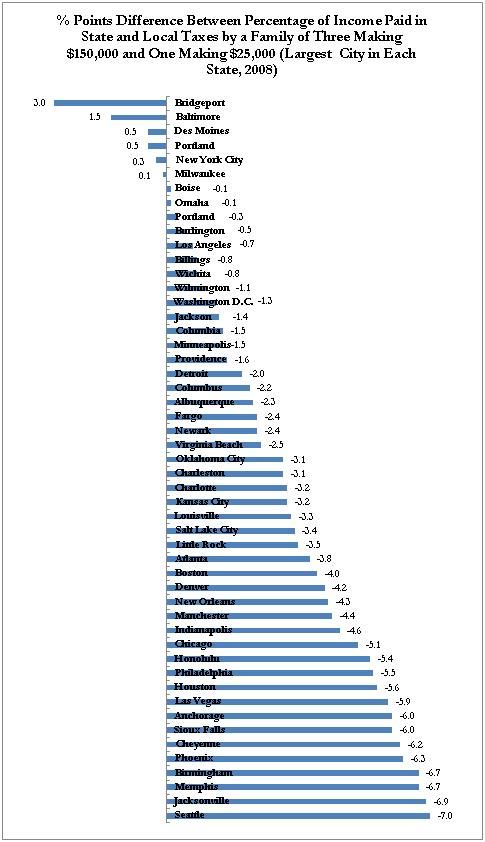

But the story doesn’t end there. State and local governments are quite aware that the taxes they raise are deductible from federal income taxes. Thus, state and local governments have an incentive to hike taxes on wealthy taxpayers, who will shrug off the increase because they can deduct it from their federal tax burden, as opposed to hiking them on poorer taxpayers, who are less likely to itemize and so more likely to be harmed by the increase. This should have the effect of increasing the tax burden on wealthy taxpayers at the state and local level.

In fact, recent research suggests that state and local deductibility makes state and local taxes more progressive while still making federal taxes less so. One study estimates that the effect is significant:

Deductibility of state and local taxes has an economically important influence on subnational tax progressivity. A five percentage point increase in the percentage itemizing (about 16 percent) would increase net progressivity by six percentage points, or about ten percent. The magnitude of the effect implies that eliminating or curtailing the deductibility of state and local taxes would substantially reduce the progressivity of subnational tax systems.

It’s important to note here that state and local taxes are already incredibly regressive, as I wrote about in a previous post.

But it’s also important to note that Kwak’s assertion that deductibility is a much better deal for Greenwich than it is for Hartford remains true: The incentive for state and local jurisdictions to make their tax codes more progressive is strongest in places where decoupling taxes paid from benefits earned — that nasty thing known as redistribution that helps fund the health and education programs the Times is so concerned about — is of least concern. Deductibility might lead to more progressivity in all the wrong places.

Along with this significant wart, deductibility for state and local taxes is also an awfully blunt way to subsidize state and local governments, since he federal government has no control over what the subsidy is spent on. Plus, deductibility is pro-cyclical: The value of the subsidy lessens as state and local tax revenue declines when the economy gets tight.

The case for keeping the state and local tax deduction isn’t nearly as straightforward as the Times editorial makes it out to be. But getting rid of it isn’t costless either.