The extremity of singular crimes, like that which took place at Sandy Hook, makes it seem possible that tragedy could happen anywhere. Mass shootings are disjointed from any process of violence that we think we understand, and so their fallout hits us particularly hard.

This can at least lead to some positive social changes, as the renewed discussion of gun control — not to mention the instant backlash against today’s NRA press conference — demonstrates. But it can also, at least from a policy perspective, be counterproductive: Legislating against guns in the context of a mass killing inevitably obscures the actual gun problem in the U.S.

The truth is that gun violence is not distributed randomly across the country. In fact, it is not distributed randomly within states. Or within cities.

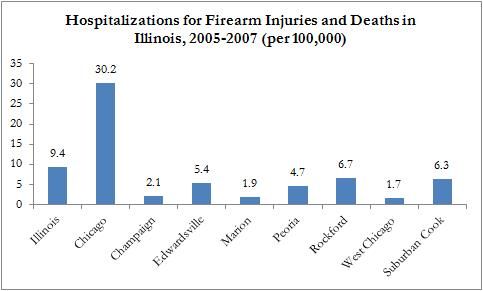

Take the case of Illinois. Between 2005 and 2007, Illinois as a whole had 9.2 hospitalizations for firearm injuries and deaths for every 100,000 citizens. The rate in suburban Cook County was 6.3 per 100,000. The rate in Chicago, however, was 30 per 100,000.

Source: Children’s Memorial Research Center

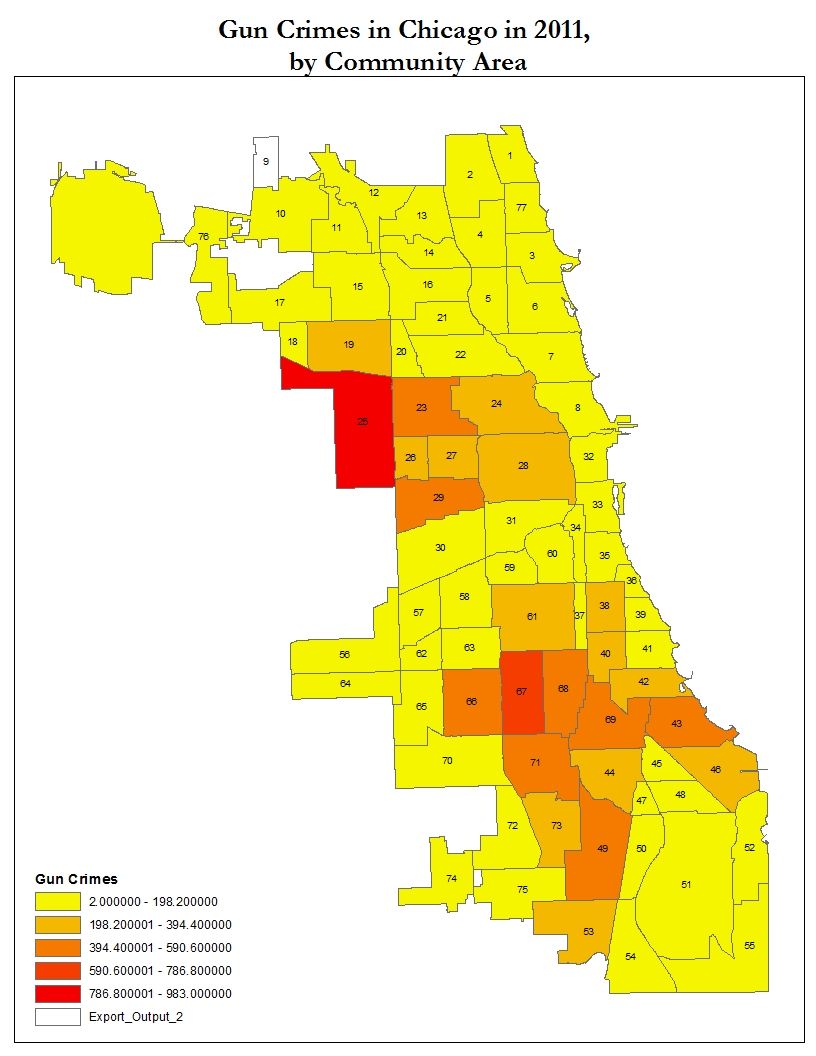

But these statistics obscure another pattern. Using crime data published by the City of Chicago, I aggregated all of the crimes involving guns in the city in 2011. These include crimes like aggravated assault and illegal possession of handguns, but do not include homicide. Clear clusters of gun crimes emerge with western and south Chicago as obvious gun hot spots.

Source: City of Chicago

However, recent criminological research suggests that my arbitrary aggregation of gun crimes at the community area level actually obscures even more micro patterns of crime. For instance, one recent study of shootings in Houston found that the probability of experiencing a second shooting increases by 35 percent once a location has experienced a first shooting. The same study finds that most of the shootings occurred in just four “relatively small clusters.”

Another study of gun violence in Boston is even more explicit:

[O]nly 5% of street segments and intersections in Boston are responsible for 74% of serious gun assault incidents even when controlling for prior levels of gun violence and existing linear and nonlinear trends. These highly active places account for the bulk of the increase in gun violence during epidemic years and the decrease in gun violence during crime drop years.

Understanding these patterns is crucial for developing effective policy responses to gun violence. But their complexity also cautions against drawing easy conclusions.

For instance, one of the most famous studies of gun laws is John Lott and David Mustard’s 1996 paper showing that concealed gun laws reduce crime. Their conclusion is stark: “If those states which did not have right-to-carry concealed gun provisions had adopted them in 1992, approximately 1,570 murders; 4,177 rapes; and over 60,000 aggravate assaults would have been avoided yearly.”

But subsequent research has exposed innumerable problems with study. Lott and Mustard’s results are driven by a few observations, suffer from methodological errors and rely on flawed data. Jens Ludwig, one of the authors who critiqued the Lott and Mustard study in subsequent research warned after the study was published that “the potential impact of Lott and Mustard’s study on policy, and ultimately on public safety, is very real” and emphasized the need to understand the methodological issues, however “esoteric.”

The potential problem with using the Sandy Hook tragedy as an impetus to talk about gun control is far less esoteric. Mass shootings are not only rare but are responsible for something like two-tenths of a percent of the firearm fatalities in the United States. While we desperately need to prevent events like the Sandy Hook shootings, there is no reason to believe that the right policy to prevent mass killings is the right policy to stop broader gun violence.

There may be no other time to talk about gun violence except after a horrific event. But the context of gun violence in the Untied States — and the incredible complexity of gun violence in the United States — must be part of the conversation.