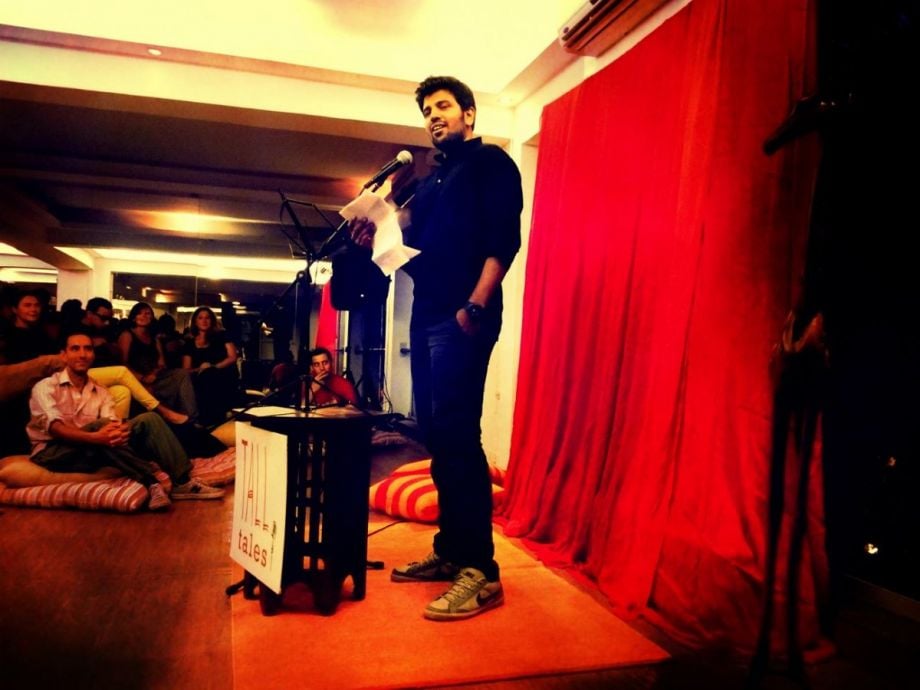

The microphone stands alone in the dimly lit loft space in a Mumbai heritage building. Rohit Nair, the first of five performers tonight, waits anxiously for the show to begin. He’s well rehearsed, ready to recount a real-life story for the t-shirt-and-jeans-clad audience. The new event, Tall Tales, part of the city’s growing arts scene, is far from the non-descript suburban IT office where Nair spends the majority of his week.

He takes a deep breath and begins: “When I was born, my sister asked, ‘Is it a boy or a girl?’ ‘It’s an engineer, replied my father.’”

The audience roars.

They’re in on the joke about the predetermined path to accepted success in Indian society. This is a country where, until recently, only doctors, lawyers and engineers garnered nods of approval from family members, who have traditionally played influential roles in deciding their children’s careers. Nair says that growing up in a South Indian middle-class family, known for its focus on education and technical aptitudes, meant that engineering was his birthright. After all, two of the world’s biggest information-technology hubs, Bangalore and Hyderabad, are in the south, and back-end corporate services are a lynchpin of the Indian economy. What Nair was actually interested in was irrelevant.

He recalls the time as a teenager when he and his father went to sign up for one of the coveted engineering seats at a nearby college. They stood with hundreds of other hopefuls, sweating for hours under the blaze of a summer sun. When the duo finally reached the front, his father announced, “as if he was buying a kilogram of Tuur Dal from an Apna Bazaar counter: ‘One chemical engineer, please.‘”

“His marks are better,” retorted the lady behind the counter. “Take computer engineering.”

“That was it,” says Nair. “My fate was decided by everyone but me. It just took 43 seconds to determine what would I be doing for a living.”

Engineering has always translated to more than a degree in India. The security associated with the professional path resonated with generations of Indians who enjoyed few safety nets. It also meant the potential to go abroad, status, monetary success and even a better marriage prospect. Yet since India liberalized its markets in the early 1990s, the country’s cities have seen an explosion of new opportunities and influences, sparking a professional awakening among one of the world’s largest youth populations. Today, a quiet revolution is in progress, as Indian Millennials do something their parents never could have foreseen: eschew the perceived security of software and microchips to pursue their dreams instead.

“There’s a sea change,” says Siddharth Shahani, executive director of the Indian School of Design & Innovation (ISDI), which opened in a 200,000-square-foot shining new high-rise in Mumbai last year. Over the last decade, new-found affluence means that young people “don’t need to think about putting food on the table… It frees them to choose the career they wanted to do.” This cultural shift has created a groundswell of new prospective students for ISDI, which plans to jump from 26 students interested in fashion, communication, innovation and interior design to 3,000 in the next five to ten years.

Hyderabad is one of the world’s IT hubs, and a reason young Indians are often expected to pursue a job in that field. Photo credit: McKay Savage via Flickr

Shahani says when he began conceptualizing the school three years ago with their New York-based partner institution, the renowned Parsons School of Design, there were only a handful of competitors in the country. Now, there are more than a hundred. The colleges are preparing for a massive opportunity in the next few years when 25 million Indians will turn 21. “Only five million of them have access to higher education,” says Shahani of the “ticking time bomb” if this demographic dividend — a view that links the rising workforce to great economic benefits — is left unfulfilled.

The higher education marketplace is responding to these emerging needs and changing interests. And as options expand, the old stand-by institutions are increasingly seeing empty seats. “B-Schools and Engineering Colleges Shut Down – Big Business Struggles,” announced a study released in 2013 by the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM), which found that just one in 10 students – not including graduates of the country’s top 20 business schools – landed a job just after graduating, compared to 54 percent of business school graduates in 2008. Not surprisingly, enrollment began to drop, and in 2011, 53,000 engineering seats in the southern state of Tamil Nadu were left vacant. Even coveted Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) have been struggling to fill many of their programs.

Nair, for his part, says he went knocking on company doors for months before he found a position and, when he did, was paid less than $200 a month, on par with domestic help or a driver. At his first job, he was helping “clients” print labels and navigate the basics of Microsoft Word – hardly what he thought he’d be doing with a software engineering degree.

Shahani says the generations of doctors, computer scientists and engineers served a great need as the country was building up, and carved out an important specialization abroad. “But India is changing, and there’s a need for more options.” Capturing the spirit and energy of today’s youth requires a potpourri of professions and, with these new choices, more focused career counseling to strategize appropriate decision-making.

The growing number of non-traditional higher education institutions are catering to a generation connected to the world through television, iPhones and movies. “Bollywood and Hollywood have been major influences,” says Shahani. “It’s exposing youth — some of whom still may not have access to the Internet — to different ways of life.”

Nair agrees. He says there’s been a trending theme in recent releases to “break out of the typecast.” Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (“You Don’t Live Twice”), for example, grossed over $24 million and was a critical and commercial success. The title underscores the attitude entering Indian society. The film follows three friends as they face their fears and seize the moment, hopping around dreamy locations such as Costa Barcelona, Seville and Pamplona. “These movies are a huge hit with the young people today, and I mean huge,” says Nair, adding that recent movies like Rock On carry similar themes. “It’s just that people have realized it’s okay to break the stereotype and do what they desire.”

Bollywood fantasy worlds aside, Gideon Arulmani sees firsthand this struggle of urban youth to find the right path. Founder of the Promise Foundation, a career counseling and research center in Bangalore, he saw 110 28-to-32 year olds come through his door last year disgruntled by their work. Ninety-two percent of them were from the IT sector. “These young people chose careers five-to-eight years ago based on labor market demands rather their own interests and aptitudes,” Arulmani says of the explosion of IT sector jobs during the outsourcing heyday. “Their frustration is linked to being skilled for the ‘wrong’ profession.” He believes the government’s relentless focus on skills without the proper guidance toward career prospects and options is only exacerbating this problem.

For instance, India’s massive job-preparation initiative, the National Skills Development Corporation, is a public-private partnership supporting training ventures in 21 key sectors. It is one of the biggest countrywide efforts in this area, and the government has invested upwards of $400 million into its flagship program as part of a larger initiative to prepare 500 million youth for the workforce by 2022.

But, as Arulmani has experienced with his youth clients, mounting frustration in these “skilling” sectors has led to widespread unemployment. Many trainees are dropping out of programs or not accepting offers upon completion. Today, young job seekers make up nearly 50 percent of the unemployed in the country, according to a report published earlier this year, “Combating Youth Unemployment in India.”

Back at the ISDI towers, the first batch of design students has a special project. Like all their projects, it’s based on their home city of Mumbai. They need to find an unusual tradesperson, like a balloon seller who peddles his rainbow-colored inflated balloons through the streets, and map the entire process of creation, business and daily life. “We wanted to be in the heart of the city,” explains Shahani, “because the students give and take so much from the city.”

Down the road from ISDI, a funky upstairs apartment with a wrought-iron spiral staircase bifurcating workstations and meeting rooms is filled with the city’s socially minded. The space, Unltd India, provides support to budding social entrepreneurs who are tackling the country’s most pressing issues: providing clean water to rural villages, sports programs to slum youth and microloans to tribal women. The co-working area is abuzz with young entrepreneurs from diverse social and economic backgrounds, some of whom come from the slums themselves and others of whom have left lucrative careers. They all, however, share a common dream to work for a cause they believe in.

Apu Kothari is one of them. Kothari founded No Nasties, a trendy organic t-shirt company, after hearing about a rash of farmer suicides in rural India. At that point, he was living the Indian dream: an engineering degree, graduate school in the U.S., stints in Silicon Valley and then a management-level New York IT job. Everything was going as planned. But this self-described happy-go-lucky guy began to feel a higher calling.

As a child, Kothari dreamed of becoming a pilot, but genetics sent him elsewhere. Everyone in his family — his father and all of his uncles — were engineers. “It’s just what everyone did,” says Kothari. “In school, we had career counseling, but 90 percent of the boys were told engineering was their path.” When his family heard his idea of pilot school, they suggested becoming an engineer to earn enough money to buy his own plane. Flying could be a hobby with all the wealth he would surely accumulate.

But Kothari was not completely sold. At the University of Texas at Austin, where he started out in the U.S., there was no requirement to enroll in a full-time master’s program. With few pulls in any particular direction, he wandered. “Each of the four semesters there, I majored in something else,” says Kothari. “First it was lasers, then microchip design, then computer hardware and, finally, computer software.”

Twelve years later, he was sitting at his desk in New York and reading about cotton farmers in India who couldn’t make ends meet enough to feed their families. The shame was driving them to suicide. Kothari decided he needed to do something. And he knew he needed to go back to India to do it.

He and his wife packed up their cushy lives and returned home to Mumbai. In 2011, Kothari did what he had been dreaming of: he founded No Nasties, a company whose primary measure of success is happiness. Kothari says it’s a risk he wouldn’t have taken in New York.

The city he returned to was a different place. Growing up it was all about creating a sense of security, recalls the “repat,” a name designated for Indians who have lived abroad before reverse-migrating back to their home country. But today’s Mumbai is dotted with shopping malls, Starbucks and luxury cars. “There’s a sense of comfort and confidence that wasn’t there before. There’s a feeling that we’re going to make and India is good.” Still, 60 percent of the city resides in shantytowns with an absence of toilets, clean water and other basic amenities. These issues, says Kothari, are what have drawn many of his fellow social entrepreneurs to depart from tradition and focus on making a positive change.

This new Mumbai represents a rapidly shifting India. Cities such as Delhi, Hyderabad and Bangalore have thriving arts scenes, social sectors and new business ventures. Nair, who lives in Navi Mumbai, a planned township an hour-and-a-half train ride from the heart of the city, says engaging with this urban pulse has exposed him to new interests he never knew he had. Attending improv comedy lessons and theatrical performances fill his non-working hours.

Like Kothari, Nair had thought of taking his engineering skills abroad. “But when I began exploring this side of Mumbai, I said no, this is it. In my 27 years, this is the first time I’m witnessing something of this sort. I’ll use this opportunity to see what kind of a person I am. What lies inside,” says the engineer turned part-time writer. He’s composing a book of short stories, the material for which comes from his encounters with the city’s rich scenes of daily life.

For now, Nair will remain where he is. Tradition calls, and his parents are relying on him for financial support. As he creeps toward 30, Nair has an added pressure hanging over him: he must get married or endure constant questioning in his tight-knit community.

“There is a lot of confusion, but I have to make peace with myself. Taking a risk would be foolish. I’m not talking about my life alone here. I want to take risks, but I want to be safe. I’m trying hard to find the right balance now.”

Kothari’s world, with the support of his family, has expanded to live out another dream. In fact, he’s done what many urban entrepreneurs long for: last month he and his wife, who owned two trendy clothing stores in Mumbai, packed up their apartment overlooking Mumbai’s cleanest strip of beach and moved south to true beach lands: Goa. The Southern Indian state is known to international travelers for its laid-back lifestyle, where locals and foreigners alike can be seen scootering around the coast by day and hanging out at bamboo beach huts at night.

His entrepreneurial life still keeps him busy, juggling phone calls with their Kolkata-based cotton mill, employees still based in Mumbai and international clients. “It’s challenging, and there’s a lot of risks. I check my bank account more often than I did in the U.S.” When asked if he still thinks about becoming a pilot, he laughs with some respect for his family’s disapproval. “No, I realized I get motion sickness,” he says. “I guess I took the right path in the end.”

Support for international reporting in this article was made possible by the Ford Foundation.

Carlin Carr is an urban development professional interested in innovative ideas for social change.