Joanna Cruz was born and raised in Philadelphia. She’s moved in and out of the city a few times, and now lives in a small South Jersey town nearby with her two kids (ages 14 and 6) and her retired mother, whom she also supports. She works full-time at a deli, making the New Jersey minimum wage of $8.38 an hour.

“I’ve had my current job for about four years now. I feel secure, they’re not firing me any time soon,” says Cruz.

With summer arriving, Cruz knows she’ll have to have some extra cash, as she won’t be able to rely on free school lunches to feed her kids. In anticipation, she started working some extra hours in May, earning a little more than usual. To receive food stamps, she reports her income every month to the state of New Jersey.

“I got $511 in May. I turned in my income with the new hours, and in June, my food stamps were already cut,” says Cruz. “All they needed was one paycheck saying that I made more money than the last paycheck, and they automatically cut me down. There should be a grace period. Maybe two months down the line cut me down a little bit, and then at three months, cut a little bit more.”

It’s not the first time Cruz has been cornered into a lose-lose situation by the social safety net, and as far as she’s concerned, it’s likely to happen again, as long as those in power continue to make decisions based on their own personal politics instead of grappling with the realities of the system at hand.

U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan recently released a plan outlining his vision to reform welfare, workforce and education programs. In support of a recommendation to insist on work for work-capable adults on food stamps, the plan makes an un-cited claim that, “Unfortunately, recent data suggests many of them are not working or preparing for work.”

And yet, like Cruz’s family, 82 percent of American households on food stamps are working, worked recently or are seeking work, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a D.C.-headquartered think tank.

Cruz has gone to Washington, D.C., three times in the last year, delivering testimony, and meeting with legislators and staff. Witnesses to Hunger, based at Drexel University in Philadelphia, recruited her eight years ago, along with a few other women, to advocate for their families and others around improving America’s social safety net. “I wanted to get out and speak my story for the bigwigs to hear from us people at the bottom,” she recalls.

Just last week, Cruz was in D.C. for the White House’s United State of Women Summit.

“Witnesses to Hunger have been fabulous about lifting up voices of people who’ve really lived this experience,” says LaDonna Pavetti, vice president for family income and support policy at CBPP. Cruz and the other members put a face on the data that Pavetti and her colleagues have been studying for years, data that show how, contrary to claims from Ryan and policymakers from both sides of the aisle, work requirements aren’t reducing poverty by encouraging work.

“It doesn’t mean that we should not try and help people get to work,” Pavetti argues. “That is something that I believe in, but work requirements will not do what the Republican leadership has said they will do.”

Pavetti has been working for a while now to debunk the notion that work requirements in the social safety net reduce poverty. That claim, as she argues in a policy briefing issued just ahead of Ryan’s plan release, goes back to two studies of cash assistance welfare programs, one in Riverside, California, and one in Portland, Oregon. The studies commenced prior to the landmark welfare-to-work reforms of 1996.

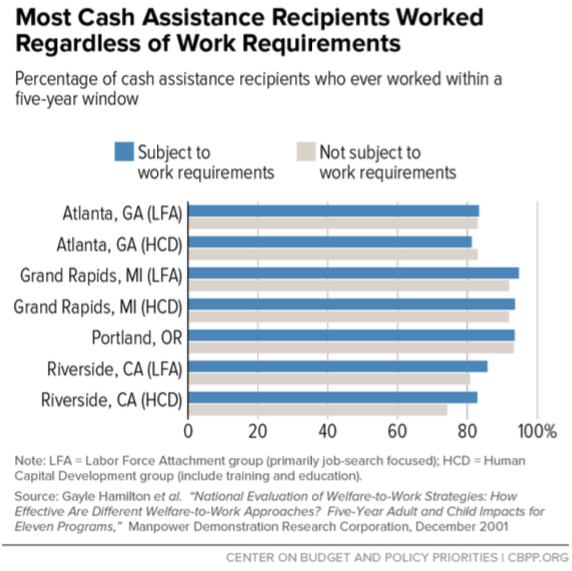

In each case, welfare program administrators assigned cash welfare recipients randomly into two groups. One was required to work to receive cash assistance; the other received cash assistance without work requirements. In both Portland and Riverside, in the first two years of the experiment, the first group did see a significantly higher percentage of recipients who worked. In Pavetti’s view, pretty much every claim that work requirements incentivize families and therefore lift them out of poverty can be traced back to studies on this experiment.

But here’s the thing: The studies on Portland and Riverside were part of a group of 11 studies conducted all across the country, that all did the same thing, at around the same time. In the other nine, the work mandate hardly increased the percentage of cash assistance recipients who worked in the first two years of the study, if at all. In Oklahoma City, there was a slight decrease in the percentage of recipients who worked in the first two years of the study.

And here’s another thing: The nine studies all continued to track cash assistance participants beyond the first two years. By year five, the groups that had work requirements for cash assistance, and the groups that didn’t, were working at nearly the same rates.

“As time went by, those differences went away,” Pavetti says. Essentially, Pavetti is saying that not only have some policymakers been touting work requirements based on the results of only two out of 11 studies when the other nine say differently, but those same policymakers also ignore the reality that people living in poverty need no special incentive from the social safety net to find work.

To cap it all off, looking at the same 11 studies and similar ones conducted later, despite increased earnings from employment, the poverty rate didn’t decline among those required to work, because recipients’ earnings gains generally weren’t large enough to lift them over the poverty line and were offset in part by reductions in cash assistance payments and food stamps — like what happened to Cruz this year, when she worked some extra hours in May.

On top of that, there’s another program, HUD’s Jobs Plus, that has shown evidence it can increase work participation among those living in poverty without the harm of using social safety net benefits as a stick. Jobs Plus supports employment, education and financial empowerment services onsite in public housing communities. Pavetti included it in her briefing.

“I did that because I really wanted to show that we do have evidence that if you provide an employment program where you’re not subjecting people to harm, but you’re trying to provide a positive opportunity, you can achieve positive outcomes,” she says. “It felt important to me to say there is another way to do this, and another way that doesn’t have the same negative consequences as the work requirements.”

Jobs Plus was conceived around the same time as the welfare-to-work reforms, in the mid-90s. It started out as a demonstration project in six cities (Dayton, Los Angeles, St. Paul, Seattle, Baltimore and Chattanooga). While not every site worked out equally well, over an extended period of time there was enough success connecting people in poverty to jobs and increasing their household incomes that in 2015, HUD announced the expansion of Jobs Plus to nine more cities (including St. Louis, where residents have played a key role in launching the program).

Why not take Jobs Plus national? Patience and perseverance, according to Pavetti. “You feel lucky when you get some expansion, some movement. So you take those incremental changes hoping that if you come up with another set of positive findings you will continue to build the case,” she says.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)