Today we mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the civil rights demonstration where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Five decades later, the March has come to represent a high point in the nation’s democratic history and, alternately, is recalled as a much-needed interruption for a land at odds with its founding principles.

It’s no doubt a strange time to reflect on the status of the demonstration’s legacy. This summer has, like the months preceding August 1963, been stained by racial violence and injustice. We saw George Zimmerman acquitted for the killing of Trayvon Martin and the Voting Rights Act dismantled. A judge deemed New York City’s stop-and-frisk practice unconstitutional, only to see it defended by the mayor and copied in other cities — including Detroit, which sunk into bankruptcy and lost its right to elected leadership. School closings in mostly black and Latino neighborhoods in Philadelphia and Chicago also challenge the long trajectory of the March.

Narratives of racial progress and anxiety, coexistence and violence are at the center of this year’s March on Washington commemorations, forging what Jelani Cobb describes in the New Yorker as “a bizarre dissonance” in which a commemorative history of social change is deeply at odds with itself.

That dissonance was audible last Sunday when NBC re-aired its pre-March 1963 broadcast of Meet The Press, a piece of vintage television in which King and NAACP Chairman Roy Wilkins were aggressively tasked with questions about the potential for riots and violence among protesters. None of the white television anchors inquired about the possibility that the violence could stem from the other side, racist vigilantes or failures of the law. (The generally triumphal gatherings in D.C. this week will no doubt be brought into somber relief next month, when Birmingham, Ala. marks the 50th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.)

Fast-forward and these exchanges powerfully recall coverage of the pre-Zimmerman trial verdict. Pundits from many news sources subjected television audiences to dangerous conjecture about, again, a foregone conclusion of African Americans rioting in the face of perceived injustice. No such rioting took place in either case, nor many retractions or apologies to note. There were many examples of peaceful grassroots social action in the wake of the verdict, like the Dream Defenders occupying the Florida capitol, but fear-based reporting continues to register. In each moment 50 years apart, the made-for-TV newspeg pivots on deep-seated mistrust of black Americans. As Stephen Colbert pointed out in his punchy satire, “You’re not holding up your end of what we said you would do.”

As we reflect upon the anniversary of the March, we also must understand the dilemmas of our current moment, and the ways that race is both central to conversations about American identity and simultaneously disavowed — especially in regard to the Obama presidency. (Imani Perry’s important book, More Beautiful and More Terrible, is a must-read on this subject.)

This week, if we note the resemblances between 1963 and 2013, we should also approach the cultural memory of the March through the perspectives of attendees themselves – to glean knowledge from the ground-up from those who joined together on the National Mall back then, those who may have returned this month as a ritualistic pilgrimage, or those who embark on the Mall for the first time.

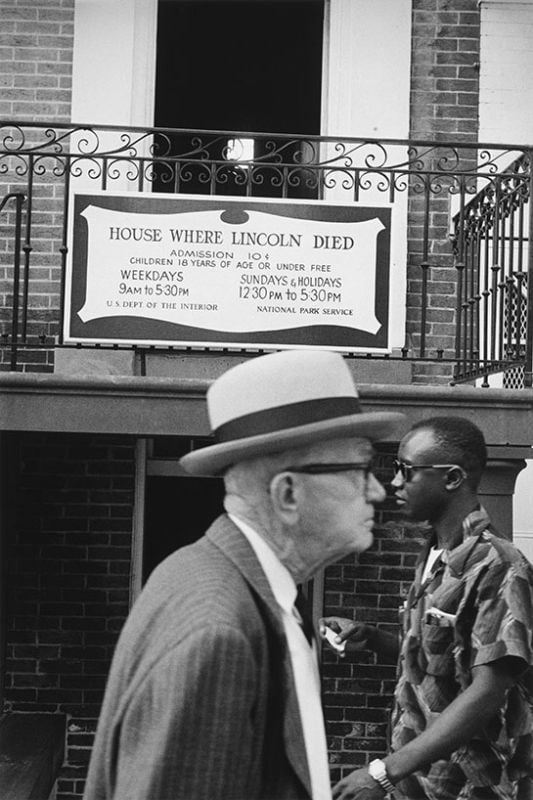

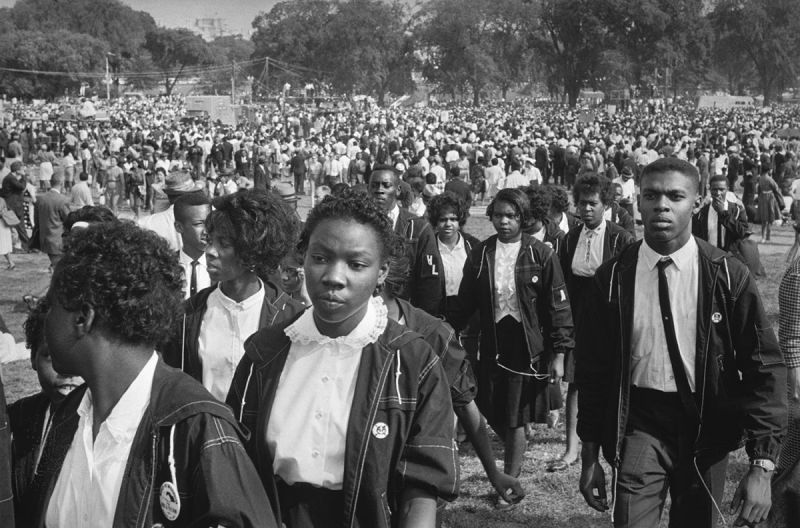

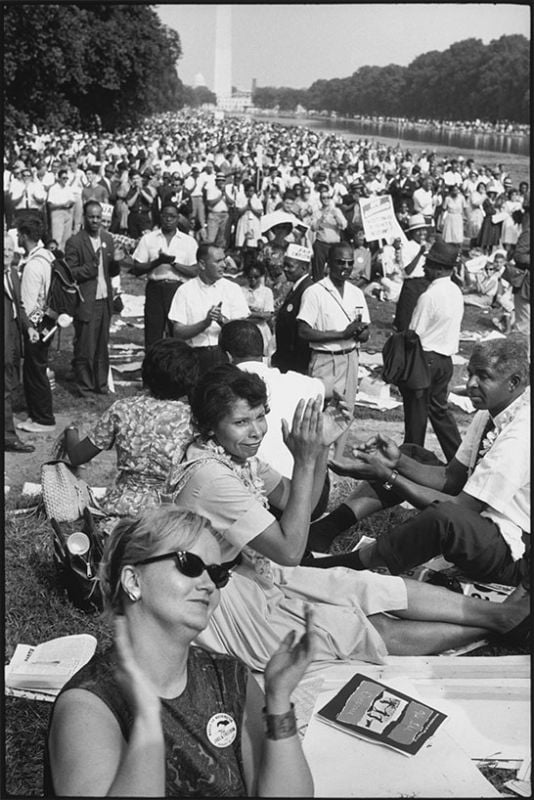

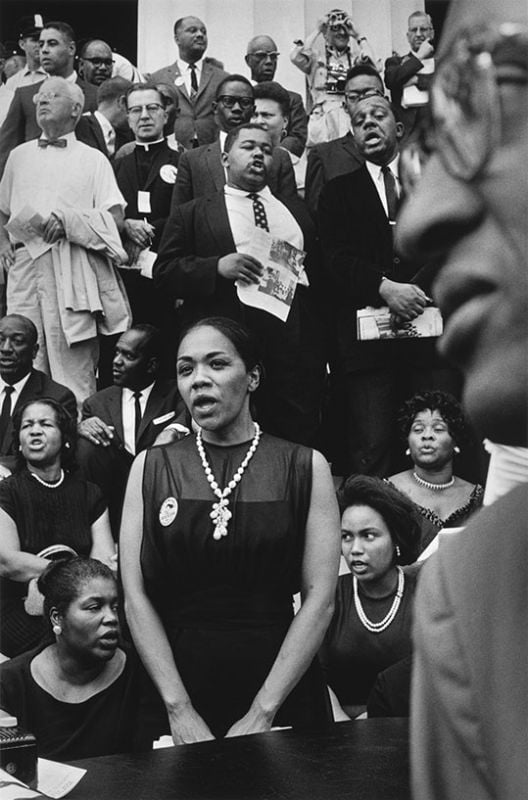

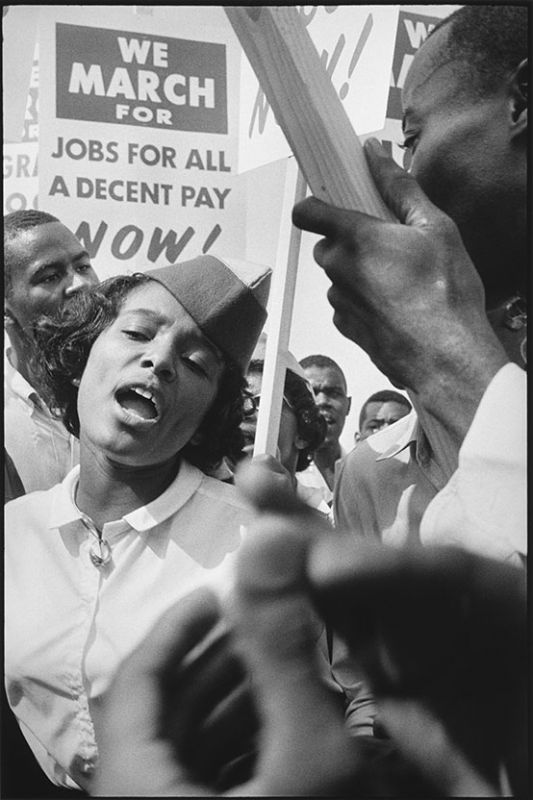

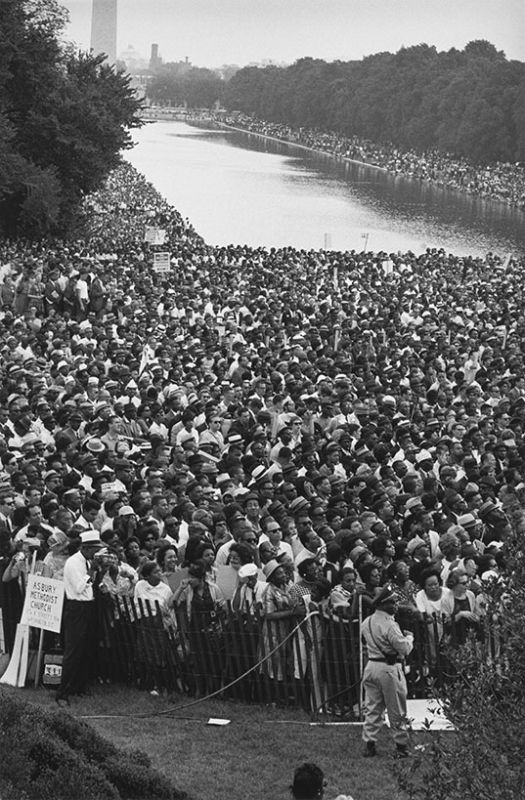

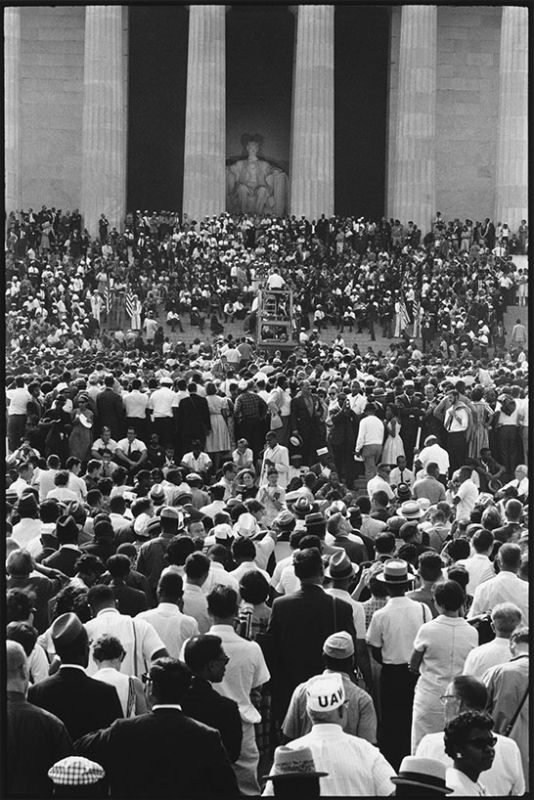

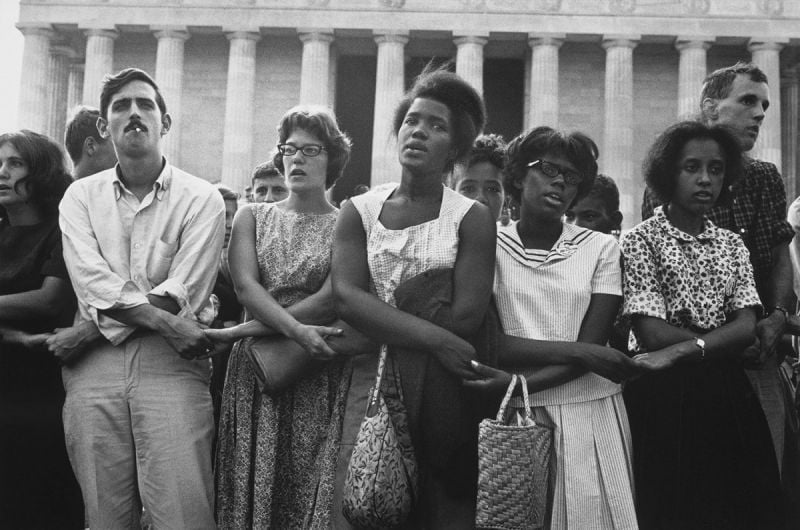

Gallery: Photographs from This Is the Day: The March on Washington

I have had the fortune of interacting with many veterans of the March and aspiring marchers over the course of the last four years, while working with the family of late social documentarian Leonard Freed to posthumously publish This Is the Day: The March on Washington, a book of his photographs taken on August 28, 1963.

Freed, a member of Magnum Photos, passed away in 2006. He left behind an immense archive of more than 1 million images, as well as the classic 1968 book-length photo essay Black in White America which featured four of his 500-plus images taken at the March on Washington.

Freed’s widow, Brigitte, attended the March with him in 1963. But it wasn’t until hearing Obama, then a presidential candidate, refer to it in a 2007 speech that she decided to return to her late husband’s unpublished images. She was inspired by Obama’s identification with the marchers. “I am here,” he said, “because somebody marched.”

This Is the Day reflects Freed’s approach to photographing American racial relations. He arrived to the scene early and stayed late, moved through the crowd as a participant rather than capture action from the side, and framed the dignity of the marchers as well as the simmering tensions put aside for the sake of coexistence. Whereas many of the prominently circulating photographs of the day feature King at his moment of great oratory or smiling with a sea of faceless attendees behind him (and powerfully so), Freed’s images evince another take: The presence and visual perspectives of the marchers themselves.

His attention to details brings the massive event to an intimate scale. A young man cups his hand around his mouth to make his protest calls more audible; schoolchildren in zip-up jackets walk up the hill of the Washington Monument while others eat popsicles to cool off in the sweltering heat; groups of marchers join hands and sway to “We Shall Overcome” with a cloth handbag draped over one woman’s arm.

Freed also returned to document the commemorative event in 1983, and other times afterward in which democratic communion and/or dissent summoned protesters to the National Mall, in order to examine the March’s ongoing influence.

Beyond the inspirations for This Is the Day, Obama’s ascension to the oval office is more broadly entangled in the legacy of the March. The first black president of the U.S. is scheduled to speak from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial today. But even that bittersweet moment will not be without controversy.

Obama’s presidency opened with broad assertions that his election signaled the “fulfillment” of the dream. Five years later, protest signs at a recent appearance in Berlin pair an image of King, presumably at the March, with one of Obama against a plain backdrop. The signs offer a stark contrast between the leaders with two phrases positioned beneath their pictures: “I have a Dream/ I have a Drone.”

This discourse now enters the living archive of the memory of the March on Washington. Obama’s hope, like King’s dream, is not a finished concept. It instead continues to be scripted, revised, critiqued and remixed in the nation’s capital and throughout the world.

Paul Farber is a Writing Fellow at Haverford College and a co-author of This Is the Day: The March on Washington.

Paul M. Farber is a Postdoctoral Writing Fellow at Haverford College and the curator of The Wall in Our Heads: American Artists and the Berlin Wall.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)