Phnom Penh has an official protest site called Freedom Park, and it’s being blocked by reams of barbed wire and truncheon-wielding thugs. Essentially designated as a free-speech zone by Cambodia’s 2009 Law on Peaceful Assembly, the park has become a flashpoint in Cambodia’s ongoing political deadlock.

For several years, the central three-acre park served as the occasional rallying point for various rights and labor groups (if they numbered less than 200 and received official permission first). But most of the time it was a quiet place, an exposed square ringed by small trees where you could sit on a stool enjoying spicy green papaya salad and cool cans of Angkor beer while escaping the city’s noise and heat.

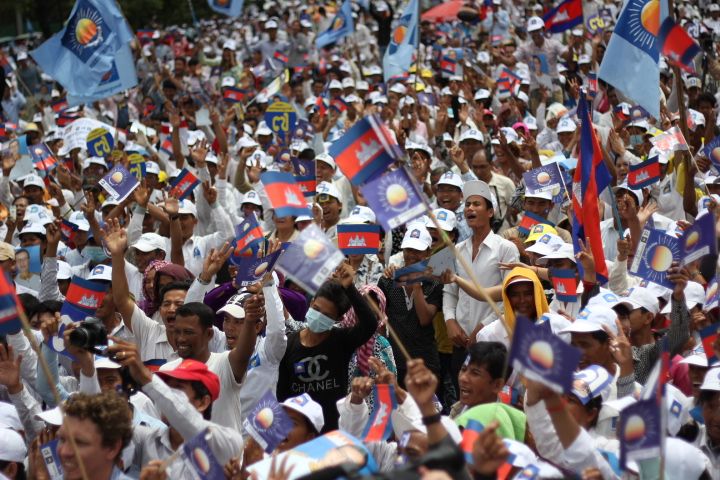

When Cambodian opposition leader Sam Rainsy returned to Phnom Penh in July 2013 after nearly four years of self-imposed exile in France, more than 100,000 people lined the city’s streets to greet him. Rainsy, who had received a lengthy prison sentence in absentia on politically motivated charges, arrived in the capital just days after being granted a royal pardon – and only nine days ahead of the country’s July 28 general election. Surrounded by a throng of adoring Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) supporters, Rainsy took to a stage in Freedom Park where he vowed to put an end to the authoritarian and kleptocratic rule of Prime Minister Hun Sen, the one-eyed former Khmer Rouge guerilla who has stood at his country’s helm since 1985, making him one of the world’s longest-serving leaders.

Amidst widespread (and credible) accusations of electoral irregularities and fraud, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) declared a narrow win in the poll. Rejecting the official results, Rainsy proclaimed that his party would boycott parliament until the government agreed to a recount, an independent investigation, or a new election. The CPP refused and the CNRP took its cause to the streets, providing the CPP with the first major challenge to its power in more than a decade.

Freedom Park became the CNRP’s main rallying ground. Numerous demonstrations were held at the site, some of which lasted days and attracted tens of thousands of people. With live music, colorful banners, impassioned speeches, young volunteers handing out food and water, and a tangible feeling of hope, the initial rallies had a festival-like air. People from the provinces even camped out in the park.

Compare this with a typical (though rare) CPP rally: freshly pressed Hun Sen t-shirts, loud pop music, stilted enthusiasm and buses waiting to take the paid attendees home.

Early attempts to intimidate CNRP supporters failed, and rallies continued despite occasional beatings, the discovery of explosive devices near the park (reminding many of a 1997 assassination attempt on Rainsy) and the temporary clearing of the site so hundreds of armored police could conduct anti-riot training exercises. Other long-marginalized groups were revitalized by the enthusiasm that accompanied Rainsy’s return, and demonstrations by human rights, environmental and labor organizations became increasingly commonplace as well.

The right to assemble in Freedom Park has been under fire in the run-up to Cambodia’s election. (Photo by Daniel Otis)

It’s hard to imagine that the string of popular uprisings in the Middle East evaded Hun Sen’s attention. In repeated speeches, he even made efforts to say that he was nothing like Libya’s Gaddhafi. His regime, however, has been linked to the deaths of numerous political opponents, so it was only a matter of time before authorities began responding to the CNRP with violence.

On January 3, security forces armed with automatic rifles opened fire on a group of protesting garment workers on the outskirts of the city. At least four people were killed while dozens more were injured and detained. There had been a buildup of violence before this – the use of electrified shields, batons, tear gas and slingshots – but nothing yet of this magnitude.

Early the next day, CNRP supporters were violently evicted from Freedom Park by security forces. Disregarding Cambodians’ constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of peaceful assembly, municipal authorities briefly banned all demonstrations. While the ban was technically lifted in February, it continues to be enforced across the city.

“The main difference between a democratic and authoritarian system is freedom of expression,” says Son Chhay, a veteran opposition lawmaker. “Cambodia is supposed to be a democratic nation, and this right needs to be respected.”

Armed military police took up residency around Freedom Park, and repeated attempts to enter the site have been violently rebuffed by “district security guards” – essentially untrained thugs in blue uniforms and motorbike helmets. Dozens of people, including journalists and rights observers, have sustained serious injuries at the hands of these guards.

In May, manned riot barriers were placed on the streets leading to the park, severely affecting local residents and businesses, while the park itself was cordoned off with reams of barbed wire. In their attempts to stymie dissent, however, Cambodian authorities essentially transformed Freedom Park from a nondescript square into an obvious symbol of the anti-government struggle.

“The barricades are actually appreciated in the event of actual protests since it keeps conflict out of the neighborhood,” says Casey Barnett, president of CamEd Business School, which is located at the park’s southeastern end. Barnett complains that since the July 2013 election, customers have been unable to visit the school, and that revenues are down by 20 percent. “It would be better if the authorities consulted with local residents before designating the park a protest zone. We did not have any say in the matter. Likewise, it would be appreciated if the protestors would consider themselves a new location to relieve us local residents of this year-long burden.”

On July 15, after seven months of being violently turned away from the park, a large group of demonstrators finally fought back. Dozens of security guards were severely beaten in the melee. The clash only ended when the crowd was dispersed with a barrage of gas canisters. Eight prominent CNRP politicians were arrested and charged with insurrection following the incident. They were released on bail on July 22 after Rainsy reached a tentative agreement with the CPP. The CNRP may take their seats in parliament as soon as this week – exactly one year after the disputed election. In the meantime, Freedom Park remains barricaded.

“In Cambodia, we’ve been through hell with authoritarian governments in the past,” says Son, who is also a survivor of the genocidal Khmer Rouge. “We had no right to express ourselves, and we don’t want to go through such a horrible life anymore.”