Some people call it North Philly, others Old Kensington. Sarah Gearhart just gives cross streets: north of Girard, west of Sixth, east of Front and south of Berks. When Roi Greene moved in 15 years ago, he knew it as the border of the Badlands. Now, condos are popping up on either side of his house.

For the purposes of the Philly Block Project, it’s South Kensington, rendered in photographs new and old. The Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC), along with conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas, curator Kalia Brooks and others, spent a year both collecting residents’ photos into a neighborhood archive and photographing roughly three blocks as they exist today. The project culminated in two shows: one of archival images and another of contemporary photos, many blown up into life-size images within PPAC’s gallery, as though the block had been recreated indoors.

An exhibition and education space inside a larger arts complex, PPAC had been around six years when executive director Sarah Stolfa decided to embark on a project that would address a tense reality for many arts organizations: They’re often disconnected from the neighborhoods they inhabit, even as they contribute to shifts in demographics, development and — it pains me to say it — neighborhood “brand.” Locals largely weren’t coming to PPAC, and when they did, there was little evidence it was a space for them.

Stolfa felt PPAC faced a choice: “Do we want to be a passive bystander in this process, or do we want to become active as a community member, as a neighbor in the space that fosters communication?”

She went with the latter, reaching out to Thomas, a New York-based artist with Philadelphia roots, and bringing on Philadelphia photographer Lori Waselchuk as project manager. Educator and artist Tim Gibbon was hired as a community organizer. “The project is as much about the process of making the project as it is about the exhibitions,” says Stolfa. Throughout the project, PPAC held community meetings where people could ask questions of the photographers, providing feedback and guidance. The team spent several months just reaching out to different blocks, looking for one that would welcome the photographers on and off for a year.

Sarah Gearhart was outside her house on Cecil B. Moore Avenue when Waselchuk came around knocking on doors. A 12-year resident of the neighborhood and lover of photography, she was all in from start. “I was really excited, I was like, you should do our block,” she says. Ultimately, PPAC did, as well as adjacent parts of North Third and Bodine Streets. “I’m an optimist, and I was a little overly optimistic about how much people would participate,” Gearhart says.

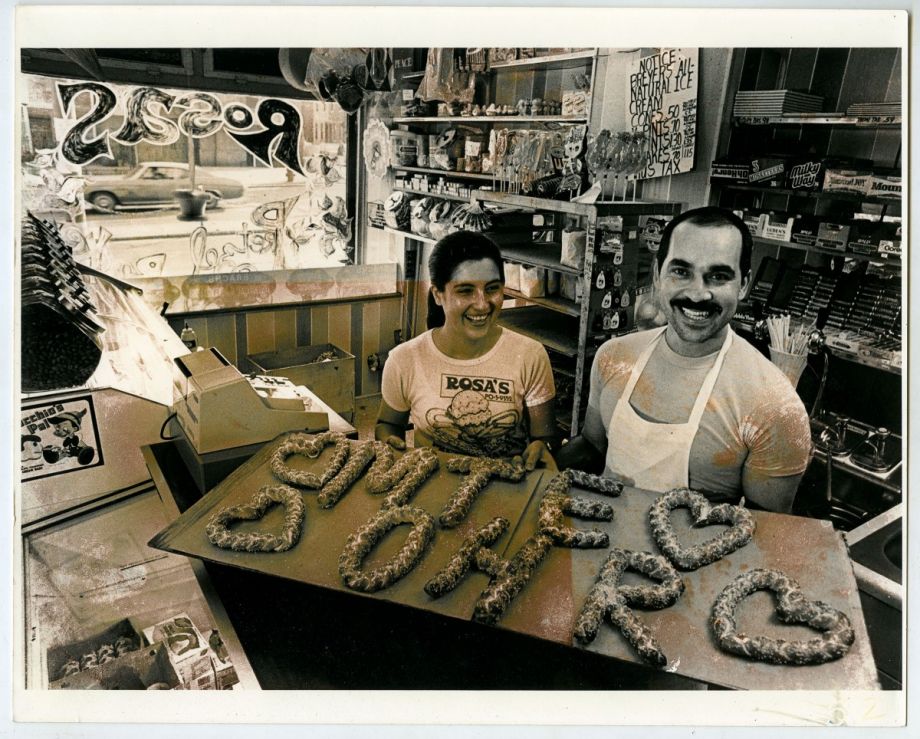

So were Waselchuck and Stolfa. The contemporary photography aspect of the project required people to open themselves up to Thomas and the four other photographers he brought on board. But the archive turned out to be the real challenge. PPAC hosted events at local hubs where residents were invited to bring their photos of the neighborhood to be scanned. They scanned at restaurant El Principe, at Islamic school and mosque Al-Aqsa, and at Rosa’s Deli, the first Puerto Rican pretzel bakery in the city.

Rosa's Deli (Credit: the Philly Block Project)

There, Gibbon wedged himself and the scanner between refrigerators and the deli for hours, but as with the other public scanning events, few people came. “They didn’t know what it was,” says Frances Rosa, co-owner of the deli with her husband Herb for four decades. But she was happy to share newspaper clips marveling over the city’s first Puerto Rican pretzel bakery and a photograph of the German owner they’d bought it from. Not everyone was so willing at first.

“It’s just a big ask to ask people to share their personal, intimate stories and to share their photographs,” says Gibbon. “That flimsy piece of paper might be the only memento that you have from your grandmother, and there’s so much wrapped up in that, and then sharing it with a total stranger.”

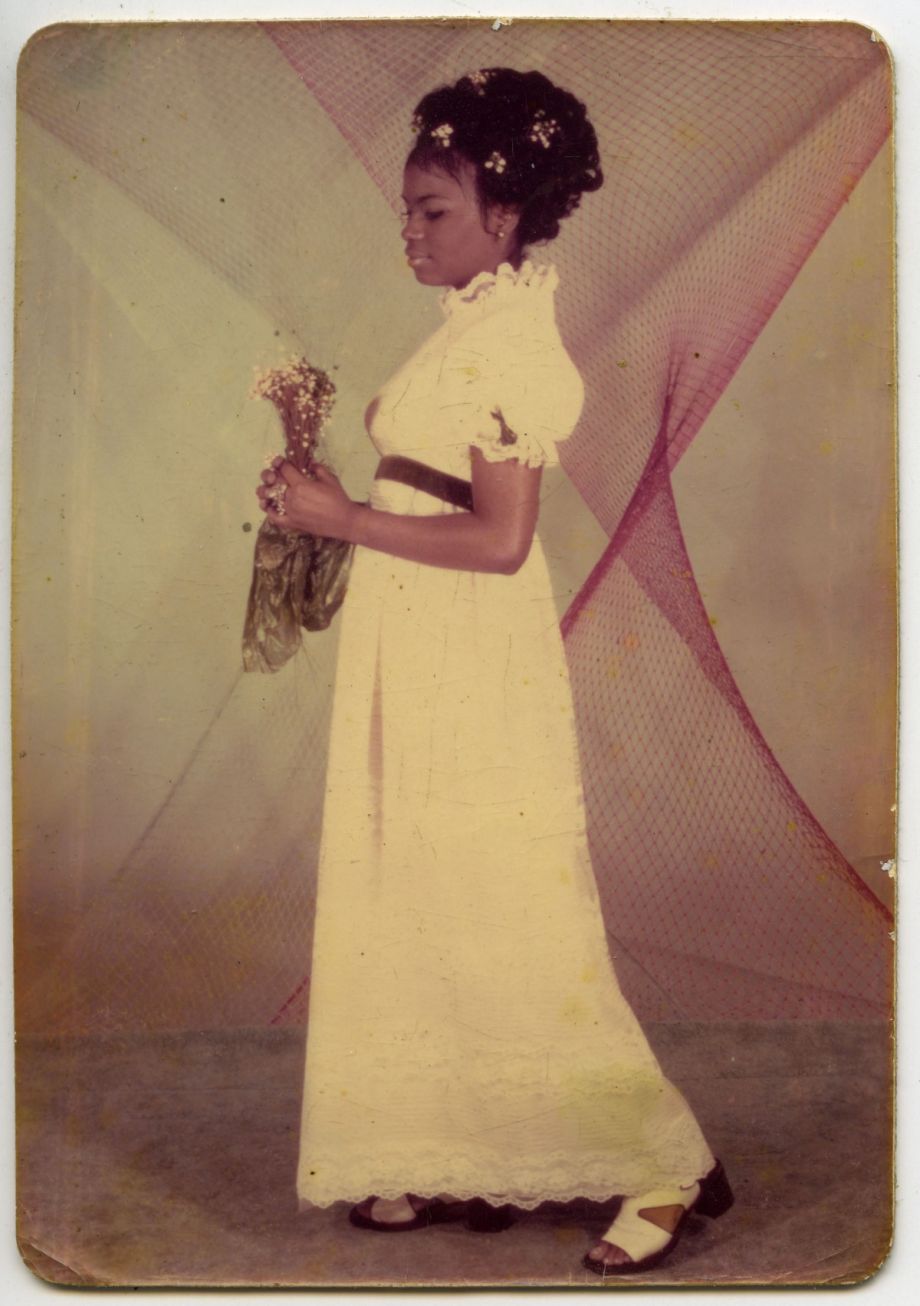

A photograph of Donna Marie Greene from the 1970s, submitted by Roi Greene (Credit: the Philly Block Project)

Others couldn’t picture the end goal. Artist and researchers salivate over archives, laughs Stolfa, but a lot of residents didn’t understand where their photos would end up. Some were skeptical of the whole premise. One woman told Waselchuk she wanted nothing to do with it. She saw the project as part of the churning mechanism attracting more people to the neighborhood and driving older residents out.

“We wanted to create a project that instead of reimagining a newer, hipper neighborhood, we wanted to visualize and entrench the landscape that is here. We wanted to really root the people’s lives and the people’s histories that are here right now,” says Waselchuk. “It can solidify their place here and honor their place here, and acknowledge that they are the neighborhood, not all the empty lots that all the developers have their eyes on.”

What role newcomers should play in honoring and preserving what came before — and what’s here now — is a fine line. Gentrification is often seen as an economic phenomenon, but it’s also a social one, a failure to acknowledge current residents and their cultural contributions to a neighborhood. “Gentrification, commercialization and development has never been kind to building neighborhoods and histories and communities,” says Waselchuk.

I’m implicated here too. I moved into South Kensington this summer, and within a week three neighbors had already told me they plan to cash out on their buildings and move on when a luxury apartment complex opens on our block in the next few years. Most bought their buildings for less than $30,000. They’ll make more than 10 times that when they decide to sell.

And Gearhart acknowledges that because of the history of this neighborhood — large swaths of which remain vacant, particularly where the city called eminent domain around American Street in a faltering bid to maintain an industrial corridor — residents have good reason to be distrustful. She sees the archive as a valuable resource, but says it’s a thorny question: “whose story is it to tell, the neighborhood’s story?”

Sarah Gearhart (Photo by Hank Willis Thomas and Wyatt Gallery)

For skeptical neighbors, PPAC made an effort to open as many doors as possible. The project also included arts workshops and the creation of a small outdoor event space. One of Gearhart’s neighbors had no interest in the photography aspect, but she was all in for the concrete planter workshop. In the end, Gearhart is glad the archive will exist. “As the neighborhood changes and people move out and older people pass away and their kids don’t keep the memories, keep the photos, keep the house, all of that’s disappearing,” she says. “I think it’s good they collected it when they did.”

As people bought in, the project “kind of grew by its own momentum,” says Gibbon. In the end, nearly three-quarters of the photos in the archive were gathered not at public events but in people’s living rooms. As the project’s community organizer, Gibbon lugged a professional-grade scanner the size of a bloated suitcase all around the neighborhood, knocking on doors and sitting for whole afternoons as people pulled out their boxes of photographs and their decades of stories. By the end of the year, over 1,500 photos were gathered from neighbors, and another 1,500 from institutional archives.

For the contemporary photographs, the original plan was to photograph all the way around four sides of a block, as Thomas had done in an earlier project in Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, but the photographers ultimately expanded to photograph sections of three blocks. The photos pasted to PPAC’s walls are almost unilaterally sunny and larger than life.

“We were very conscientious about the doom and gloom, because that’s expected,” says Brooks. “There’s a lot of ruin porn, there’s a lot of urban blight, and we didn’t want to tell the same story. We wanted to make sure there was brightness, there was life as a part of the project.”

For the archival photos, the plan was to stick to the boundaries recognized by the South Kensington Community Partners neighborhood association: Girard Avenue to Berks Avenue, and Front Street to Sixth Street. But in the end, “we opened up a little wider because it felt necessary to take that kind of creative license to open up the context a little bit more,” says Brooks, who curated both exhibitions.

Sometimes photographs from outside those boundaries could still illuminate the neighborhood’s history. Many Puerto Rican residents, for example, had previously been pushed out of the Spring Garden neighborhood; some of their photos from that time made it into the archive.

Now some of Frances Rosa’s long-time customers are getting pushed out of this neighborhood, too. She’s watched four or five changes pass by over the last 40 years, but this is the largest, she says — the young people and urbanites, as she calls them, moving back into the city from the suburbs. Just up the block, both sides of the road are fenced off while condos sprout behind them. When they’re finished, there will be nearly as much new construction on this block as old. Now she and Herb are selling the shop again, and she says it’s not young people looking to buy like they once were, it’s developers. At the opening of the archival show — where some of her newspaper articles were blown up and hung — she saw neighbors she hadn’t seen in years.

Roi Greene and family (Photo by Hank Willis Thomas and Wyatt Gallery)

Roi Greene is thinking of cashing out too. A self-described ham, he liked participating in the project because “I just wanted to be a part of something motivational and positive,” he says. The exhibition of contemporary photographs — on display at PPAC until November 30 — includes many of Greene. The hundreds of photos in the show are tiled like bricks or blown up like doors and windows, to suggest the neighborhood is, in fact, made up of people, not development opportunities.

The installation (Credit: Philly Block Project)

“You can never get a complete picture of what the neighborhood is because it’s so complicated,” says Gibbon. “And it’s amazing how one geographic place can mean so many things to so many different people.”

Stolfa hopes after the exhibition comes down in November neighbors will still feel welcome at PPAC. She and Waselchuk are still figuring out what should become of the archive. They want to keep collecting. Temple University has offered to house it in their online library, but PPAC wants to make it more readily accessible to people too. “The whole project, we have to remember, is not just about the curation and grabbing of these photographs,” Stolfa says. “It’s also about creating relationships.”

This article is part of a Next City series focused on community-engaged design made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)