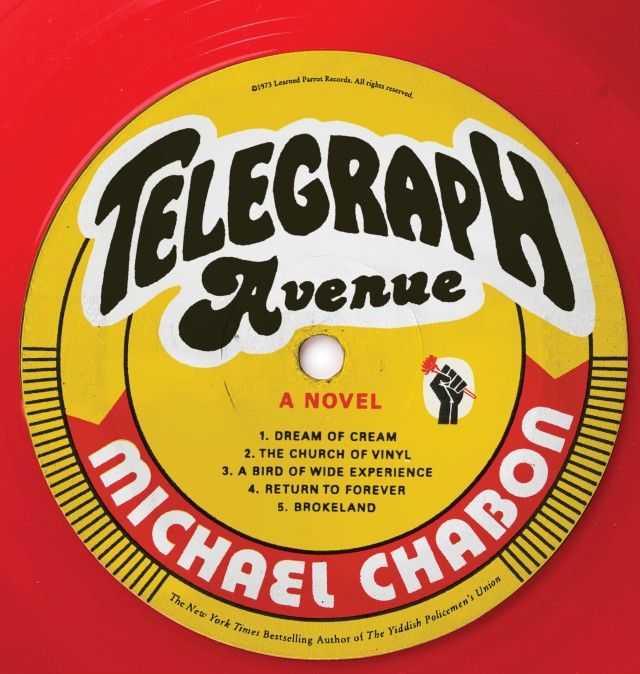

Are there really that many people still buying vinyl records? Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, a book that’s about 40 percent about how urban communities face change and 60 percent about how families face it, keeps coming back to vinyl. All along, you have to ask yourself whether vinyl really means enough to people to keep small record stores open.

It’s an important question, because Telegraph Avenue is written to make you care about one particular vinyl record store. Set on a street in the heart of Oakland, Calif., the novel imagines two married couples, one white and one black. The two couples are effectively married to each other, as well; the women run a midwife service together, and the men own Brokeland, the record store at the heart of the book.

The book’s central conflict is the coming of a “Dogpile Thang” chain store, two blocks from Brokeland. Chabon only sketches what Dogpile is, but it appears to resemble something like a Virgin Megastore. We know a Dogpile Thang is very big. We know there is already one in L.A. We know it is something like a mall, but with a strong orientation toward music. We learn that it will include a vinyl section that will be larger and cheaper than anything the owners of Brokeland can offer.

We also know that Dogpile an institution with a mission: To bring black employment and black economic development to once-prosperous black neighborhoods. Its owner, a former NFL star, is now one of the top-five wealthiest African Americans in the country.

Brokeland’s proprietors admit in the beginning that with or without a Dogpile, the store probably will not make it. They have never made much money and have no reason to believe that vinyl will soon surge in popularity. So the question is — and it is a question faced by business owners in changing neighborhoods all over the country — what do the owners do? Hold on? Fight? Or pack up and go?

While reading Telegraph Avenue, I happened to hear a talk on fiction writing by Kurt Andersen, of PRI’s Studio 360 and the novels Heyday and True Believers. Andersen said he usually approaches a new novel by going after some real-life issue he is having trouble taking a side on. It seems like that might be what Chabon is doing with this book, working out how he feels about the way bursts of economic opportunity can erase a lot of a neighborhood’s history. The question seems to push and pull Chabon as much as it does the two members of Oakland city council who pop up throughout the story.

For some, it is easy to oppose corporate scale economic development. It’s big. It’s disruptive. It can be gaudy. I saw this, personally, in the change that came to my former neighborhood around the Columbia Heights Metro Stop in Washington, D.C.

If you never saw the area before a giant, mall-like complex went up alongside the local Metro stop, it is hard to overstate how much Columbia Heights changed. It is as if developers didn’t understand the city in which they were building. That said, you can’t argue with this point: It’s bustling now. There was no bustle when I lived in Columbia Heights in 2001. None. It was one of the few parts of Northwest D.C. that was still a bit of a drag to live in. That’s why I lived there. I got my apartment cheap.

Columbia Heights in Washington, D.C. Credit: Daniel Lobo on Flickr

If you’ve seen the neighborhood, or any other where large-scale redevelopment has taken place, then you can imagine something of what Dogpile’s owner must have been trying to do to downtown Oakland in Chabon’s story. It would have made the place different, and it would break Brokeland.

So, would that be a tragedy? A vinyl record store lost? Two store owners out of business, but replaced by how many new jobs for folks that didn’t have them? Again, how many people still buy vinyl?

It’s not only the business Chabon wanted you to consider in creating Brokeland.. He wants you to see the community that formed around that spot. That Brokeland, like all the businesses that occupied that space before it, is a gathering place for people to swap stories, hang out, gossip and brag. Which is nice, but is it more important than opening a business that will draw foot traffic so that other businesses can grow and create something forward-looking? Is saving a record store that people really like more important than giving people from the neighborhood jobs with benefits?

In the book The Black Swan, author Nassim Taleb shows that human beings are naturally inclined to think about change differently than how change happens. We believe, deep down — so deep that we don’t even evaluate it — that change comes gradually, that it eases up on you in such a way that you can get used to it. What Taleb illustrates in example after example, is that mostly there’s no change at all, but when change does come it’s big, fast and totally unpredictable.

Clearly, there are residents of the neighborhood that don’t think the promise of Dogpile Thang is worth the cost. Or is it just that they personally won’t see any benefit?

One of the Brokeland owners organizes a neighborhood committee to resist the project, and he gets a nice turnout from all the crazy white people of the neighborhood for its first meeting. As a former community organizer myself, I cringed at the storeowner’s decision to invite one of the local city council members out to the first meeting. Chabon must have been part of these sorts of exercises before, because he accurately portrays the way politicians behave when invited to a founding meeting of a citizens’ organization. The elected official dominates the proceedings and moves quickly to bend the group to his own agenda, only to show later in the book that his resolve to keep a Dogpile out of Oakland is less than resolute.

And there are two important points to bring up about this key question of how one should feel about massive change. First, Chabon cheats. In Dogpile’s owner, he creates a character seldom seen in such fights: Someone who is from the neighborhood he’s transforming, looks like the majority of the people who live there and wants to deliver opportunity to its residents at all levels of his business. He’s a black man who wants to bring black business into a black neighborhood — hard to object to as an agent of change for Oakland. Chabon makes it all a little too easy by shucking the usual complexities of race and class and displacement that come with major projects.

Then, Chabon punts. Ultimately, this is a book in which the fate of Brokeland turns out to be the least of the two couples’ worries. There are children to take care of, babies on the way, marriages at stake, fathers to bury and forgotten affairs to contend with. A stack of vinyl in a store on the skids just did not feel, to this reader, like it was all that much to lose, and if it was lost it probably would have been lost with or without a Dogpile Thang.

Credit: Stephen Dyrgas on Flickr

Nevertheless, it is the nature of cities to change, not gradually, but in lurches. All change is disruptive, whether it is growth or decline. Ironically, growth is really the only kind of change residents can effectively protest. By the time you know decay has come, it has set in deep.

That is the question that reading Telegraph Avenue may illuminate for urbanists. We all agree that people should return cities. We want our cities to grow again. Some of them are doing so, nicely, but there are those that could do with a few Dogpile Thangs.

So the tougher question — the street-level question, the one that those who care about cities need to think about now, before it happens — is what do you do when the growth stops being theoretical? When you get growth, like you wanted, but not the type of growth you wanted? Where do you stand when whole neighborhoods take a buyout to move, like they did in Baltimore’s Middle East, or even when it’s much simpler than that, like when your favorite bakery closes because the increasing foot traffic isn’t keeping up with the increasing rent?

Telegraph Avenue asks us to start sorting out where we stand when our city gets the growth we hoped for, but learn that it inevitably means our communities will lose important places in the process. It is a tough question, but don’t read in the hopes that Chabon will give an answer. He won’t. All Telegraph Avenue does is draw a better picture of the question, and goes no further than painting a detailed, multilayered and multi-faceted portrait of what might be lost when a neighborhood stands to make a major gain.

Brady Dale is a writer and performer, currently living in Philadelphia. He can be found on Twitter at @BradyDale.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.