There is a blue light at the end of the train platform, and it has only one purpose: to stop people from jumping in front of oncoming trains and killing themselves. First installed on Tokyo’s Yamanote train line in 2009, these blue LED lights are one example of Tokyo’s idiosyncratic response to the city’s suicide rate — a rate that’s declining, but still one of the highest in the world.

Suicide is a bigger threat to Tokyo’s citizens than natural disasters and traffic fatalities combined. In 2013 a total of 2,825 people killed themselves in Tokyo. In Kanagawa, part of Tokyo’s suburban sprawl, a further 1,532 people committed suicide according to data released by the National Police Agency (NPA). Japan saw 27,195 suicides in total in 2013.

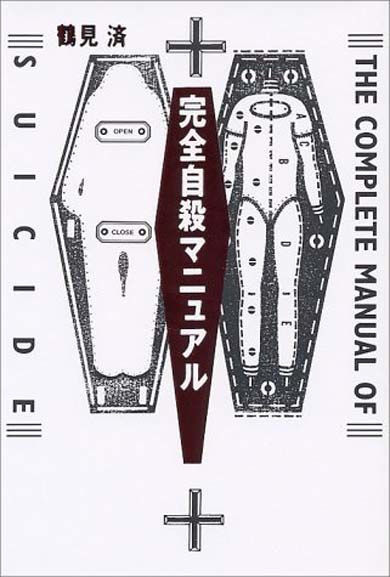

The NPA statistics show that those who kill themselves do so in a wide variety of ways: self stabbing, poisoning, hanging, inhaling noxious gases, or jumping in front of a moving train. Some look to books such as Wataru Tsurumi’s 1993 suicide manual, Kanzen Jisatsu Manyuaru (“The Complete Manual of Suicide”) Others seek advice from fellow suicidal strangers online, or in some cases meet with them in real life to join them in a group suicide. The reasons for suicide in Tokyo are even more varied than the methods, but the NPA data suggest that over half of Japan’s suicides can be linked to “health issues,” a broad category that encompasses all maladies, both physical and mental.

Tokyo’s suicide problem brings to mind questions first raised by sociologist Emile Durkhiem in his 1897 text Suicide — specifically, should we be focusing our attention on the suicidal individual or the context that may have led him to become suicidal? Do Tokyo residents need help, or should our scope be wider? To put it more bluntly, what role does the city itself play in Tokyo’s high suicide rate?

Tokyo is a model of stressful urban living. Each day workers spend an average of 67 minutes commuting, according to a 2008 article in the Asahi Shinbun newspaper. During rush hour, those 67 minutes may be spent on a train crowded with four times as many passengers as it’s designed to carry. Single-occupancy housing is on the rise for young workers, suggesting these people’s social support systems are fraying. And awareness about mental health issues is low. A 2013 report by the Japan Medical Association Mental Health Committee suggests that a major problem is a disconnect between psychiatrists and community physicians. This lack of awareness is compounded by a lingering belief that suicide is an honorable way to purify wrongdoing, and in some cases perhaps even a beautiful, romantic act. In October, Michiko Hasegawa, a member of public broadcaster NHK’s management board wrote an essay in which she cast the 1993 ritual suicide committed by a right-wing extremist in a spiritual light, writing that “he…offered his death to God,” and describing the suicide as a devoted “offering.”

Wataru Tsurumi’s 1993 suicide manual.

Director of the Center for Suicide Prevention in Tokyo, Dr. Tadashi Takeshima says there have been “three phases” to suicide prevention in Japan. The first began in 2001 when the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare put aside a budget to consider a suicide prevention strategy. The second came in 2005 when the government set out to develop Japan’s first policy related to suicide prevention — the Basic Act on Suicide Countermeasures — which was passed into law in 2006. We are now in the third phase, a period of suicide prevention based on the 2006 act.

One of the government’s main goals in this third phase is to reduce suicides by 20 percent of the 2005 rate within the next three years. The 2013 rate was the lowest in fifteen years, and marks the second year that the number has fallen below 30,000. It means that the government is getting close to achieving this 20 percent reduction, but as critics have noted, even this relatively low goal is still two to three times higher than the number of suicides in the U.S. or U.K.

The other steps in the government’s nine-step plan are more difficult and qualitative, including an investigation into the root causes of suicide, changing cultural attitudes and improving treatment of unsuccessful suicides. (Attempts may be ten times more numerous than successful suicides according to the NPA.) Billions of yen are being poured into these efforts. But is the money being used effectively? It’s hard to say when the issue is inherently existential, and the root causes so hard to pin down.

The most visible signs of suicide prevention in Tokyo are the barriers, automatic gates and blue lights on train platforms. Part of the reason the city concentrates its efforts here is because such “human accidents” are costly and can disrupt tens of thousands of passengers for up to an hour, weekly or even daily. Barriers and automatic gates are a deterrent but not a solution, however — motivated people simply climb over them. Less expensive are the aforementioned blue LED lights. A research paper published in the Journal of Affective Disorder in 2013 (four years after the first lights were installed) found that there was an 84 percent decrease in suicides at stations with the blue lights. The exact reason why the lights are effective isn’t known, but some researchers theorize that it’s related to the apparent positive effect of light on mood. A recent study led by Hiroshi Kadotani, from Shiga University of Medical Science found there was an “increased proportion of railway suicide attempts after several days without sunlight,” based on 971 suicides or attempted suicides in Tokyo between 2002 and 2006.

Less obvious measures to prevent suicide are undertaken by Tokyo police who investigate cyber crimes. These teams scour suicide websites and forums looking for at-risk individuals, and in some cases may act based on writings they find online. Also less visible is the “Inochi no Denwa” hotline, which meets a counseling need, but despite employing 300 volunteers is still understaffed and underfunded, with callers experiencing long delays.

In a city that’s already overworked, the situation will not be solved quickly. Progress is being made, but there is an inherent lack of empathy for suicidal individuals at a legal, vocational, medical and even infrastructural level. Sadly, no matter how quickly the situation changes, it’s already too late for many.

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)