Certain ideas are like moments in history, in that I can remember where I was when I first encountered a few great ones. For example, I can see my feet as I stood in the bedroom of the place I used to own in North Philadelphia, scrambling to get ready for work, when I heard a story about Dan Kildee’s “shrinking city” strategy on Morning Edition.

“Sign me up,” I thought. I wasn’t living in Kildee’s hometown of Flint, Mich., but Philadelphia too was struggling to provide services to more land than it had people for. While its problem wasn’t so acute, Philadelphia’s tax base was shrinking due to the way vacant properties stole value from those still in use.

I thought to myself, “If someone wants to tear down my block and move me into a place on now-empty land closer to Center City, I’d go.” Upping a city’s density, in general, seems guaranteed to increase its dynamism. And if you can’t do it by adding people, do it by moving the people you have onto less land.

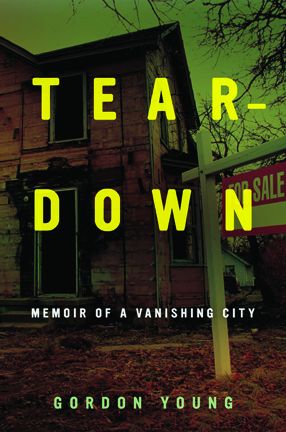

Based on the title, I was hoping that Gordon Young’s new book, Teardown: Memoir Of A Shrinking City, would document all the tearing down and building up that Kildee — now a U.S. Congressman, then head of the Genesee County land bank and treasury — had done in Flint. While the book does explain Kildee’s strategy better than I had understood it before, the concept is more of a recurring theme in a story about Young, and his fixation on the city in general. Another subtitle he might have chosen is “A Chronicle of Flint’s Affable Few,” because that’s really what’s most interesting in Teardown: The folks who have planted a stake in Flint and won’t be moved, have worked hard to be the best possible neighbors they can be, and take part in whatever gossamer strands of community remain.

The Shrinking City

The shrinking city strategy has bad “optics.” If you’re not familiar with the term, optics is the notion that how media or opinion-makers describe a given concept has a powerful effect on how people react to it. It’s easy to describe Kildee’s idea, as Rush Limbaugh often has, as “bulldozing Flint.” In truth, though, it’s using the tax foreclosure process to keep more of the ownership of vacant properties in Flint, and use some of the revenues to rehab space where the population density is stronger.

It makes a lot of sense to me, but it has bad optics. You hear folks say, again and again, “it sounds like giving up.” The trouble is, that’s really as far as the counterargument ever seems to go. Flint has lost 25,000 people since 2000. It’s roughly half the size it was during its 1960 peak of 197,000 residents. When Young wrote about Kildee for Slate in 2010, abandoned homes occupied 10 of Flint’s 34 square miles. That doesn’t count abandoned factories, either.

In other words, too many folks have already given up. Kildee clearly isn’t giving up in the book, but he is the mastermind behind a strategic retreat.

And it should be no surprise to Kildee that the population of Flint dislikes his idea. After all, the folks who stayed are the ones with the strongest emotional ties not only to Flint, but also to their specific homes on specific blocks. For example, Young takes us on a walk around Dave and Judy Starr’s neighborhood. The Starrs are pillars of their quickly emptying community of Civic Park, and are making improvements to their house that cost more than their whole property. Meanwhile, dozens and dozens of homes around them sit empty or have burned down. Whole blocks stand without a single resident.

Yet the Starrs are building a fountain. These are not the sort of people likely to get into the idea of moving to a different part of town.

Yet when I read Young’s description of the place they are holding onto, I was totally unable to fathom why. I’m not the only one: Basically everybody the Starrs knew as neighbors has gone, and very few newcomers have shown up as replacements. Furthermore, Kildee’s plan was not in place as the others went, which means no one was ready to give those folks a way to move to a more resilient part of Flint. They just left.

I’m not sure the shrinking city concept can really work. In fact, Kildee himself says that it can’t work without financial support from the suburbs. It’s hard to believe that Flint’s suburbanites would get too heavily involved with a city where hardly any of them even work any longer.

That said, it is a much better plan, in my opinion, than hoping that another GM will move to town. The city is low on vision, jobs-wise. When Young describes present mayor Dayne Walling’s economic development strategy, it sounds like he’s reading from a script faxed and refaxed between every smallish city mayor in America: Focusing on the known, hoping for a bit of what they lost to come back, and something about colleges.

Credit: John Kannenberg on Flickr

The Emotional Roadblock

Here’s what Young’s book is really about. Its author is a freelance journalist who had been living in San Francisco for years, owned a home that he and his wife could barely afford, and started feeling drawn back to his hometown of Flint. He’d grown up there as it began to fall apart — his mom’s car was hit by bullets twice on its main drag. He started a blog for Flint expatriates, which became popular and led him to think about buying a house there. He spent the better part of two summers and a bit of one winter looking into it. He had about $5,000 to work with, a reluctant wife, a half-million dollar mortgage in the Bay Area, a fear of blood and an aversion to loud noises.

Young is at his best describing the emotional stakes for the city he calls home. In that way, it’s a lot like Roger & Me by Michael Moore, though Moore’s film is long on moral outrage and short on broader context. In fact, I commend Young for grappling a little with the question that Moore studiously avoids: Had GM’s workers, and those of the ancillary businesses surrounding it, grown complacent in the assumption that the company would always be there to take care of them? GM probably did owe its workers more than it gave them when it left, but you can’t convince me that there is any moral obligation for a company to stay in one place forever.

In Roger & Me, the very outrage over GM’s departure revealed Flint’s fundamental weakness. The city had no resiliency. Its economy wasn’t at all diversified. It was a place where one board room meeting could bring devastation, and that’s exactly what happened. Its people were so hardwired for factory work that there wasn’t an entrepreneurial spirit in the city to make up the difference after the company went.

Flint could do with a lot less emotionalism. There’s a point, early in the book, when Young describes Flint’s founding as a mere accident of geography, and writes that he had hoped the city had something more special to its origin than that. Which struck me as a good illustration of the way Young romanticizes what Flint is — honestly, a one-horse town that lost its horse. Cities are, in general (but not quite all), accidents of geography. Most of them were plopped down in places that had some resource advantage for its founders. In fact, even describing an origin in that way illustrates the weirdness of letting optics shape your thinking. Doesn’t the fact that Flint’s founders considered its location useful make it special? What does “special” mean, anyway? And why does it matter?

To me, the more important question for Flint, and cities like it, is what’s best for the people who remain. That is, less emphasis on Flint and more on its residents, less about the forest and more about the trees. Because when you think of Flint, you’re necessarily going to picture its past, preserving its character and “what made Flint great.” There are deindustrialized cities that have started to make strong comebacks, but Pittsburgh hasn’t done it with a new steel facility and Cleveland didn’t do it sitting around a museum to Standard Oil.

There was nothing in Teardown that convinced me that anyone should move themselves or their money to Flint. That said, it did convince me that there are some hardworking, dedicated people determined to stay. It’s a city where some of the best possible neighbors that any block could hope for are living without neighborhoods. So, Young’s book left me wondering: What might happen in this nearly empty place if future Dan Kildees and the Dayne Wallings managed to put these best of all possible neighbors next door to each other?

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)

_on_a_Sunday_600_350_80_s_c1.jpeg)