The Los Angeles River has something of a forsaken past. For years, the Army Corps of Engineers didn’t even consider it a real river, and many saw it as a dirty concrete half-pipe that only ever played a waterway in Hollywood movies. But as Nate Berg reports in this week’s Forefront, a small grassroots push for revitalization has grown into a movement that even Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa stands behind, and now the river seems about ready for its unlikely rebirth.

From the side of a four-lane overpass in the Canoga Park area of the San Fernando Valley, 25 miles northwest of Downtown L.A., you can look down on the official headwaters of the Los Angeles River. Two concrete canyons converge, their 20-foot walls perfectly vertical and smooth, curving to meet like two lanes merging on the highway. Here the water runs just a few inches deep and spreads across a maybe 100-foot channel. On the other side of the overpass, the water below narrows into a single body and the concrete walls fan out into a trapezoid shape, shooting the river straight off into the distance.

The clean lines and angles, the plain concrete grey, the modernist infrastructure — it’s all kind of beautiful, both crude and elegant. It’s a brutish way to treat a river, but one so efficient that it’s impossible to discount the precision and scope of its engineering.

And so it goes, 51 miles to the Pacific Ocean, alternating its vertical and trapezoidal walls as it carves through the urbanity of Greater L.A. Walls climb more than 30 feet in some parts, topped off by fences and signs warning passersby that entering the river is a crime. For those not scared by the warnings, some parts of the river are relatively easy to access, with a little fence jumping and train track hopping. Once on the concrete surface of the river’s channel, there’s a distinct feeling of increased calm, even near downtown or the bustling train yards and warehouses along its sides. You’re not exactly separate from the city, but just a degree or two away from the usual background buzz. It’s the ideal environment for graffiti artists and the homeless, or even the lone egret flying low and smooth over the river between its protecting grey walls.

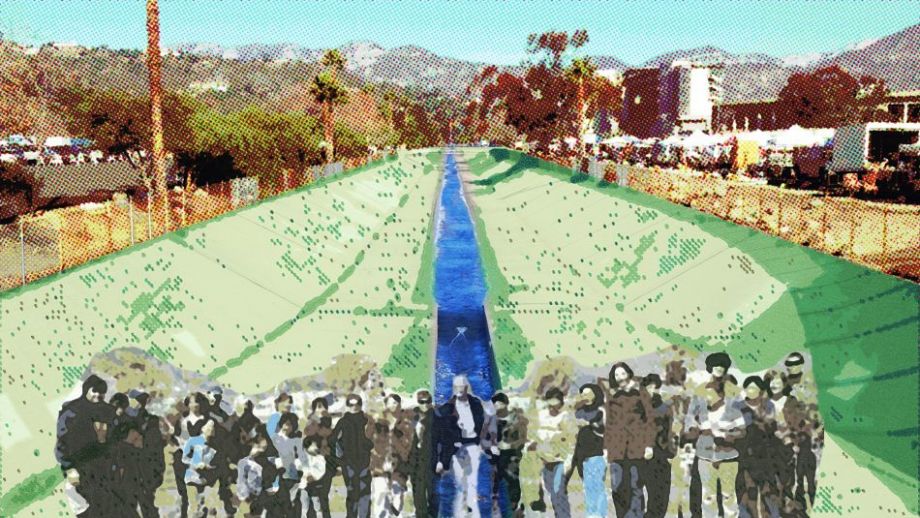

Though most of the channel is covered in concrete, there are three separate stretches, totaling about 12 miles in length, where the earthen riverbed is still intact. The underground water table is too high in these areas to cooperate with the Army Corps’ concrete plans, so they were left at least partially natural. Willow trees grow, ducks swim, cattails sway in the breeze. For a few miles in a few areas, the Los Angeles River has always been a river.

That’s how Ed Reyes remembers it. The longtime L.A. city councilmember grew up just a few blocks from a natural-bottomed stretch of the river known as the Glendale Narrows. He remembers crossing over railroad tracks as an 8-year-old kid back in the late ’60s to get to the water.

“We skidded our Schwinn bikes down to the base of the river and found this running water,” Reyes recalled in a recent interview. “There were all kinds of bushes and trees and ducks in there, and in the middle there was like a little beachhead with sand.” Reyes and his brothers used to catch tadpoles and listen for frogs, he recalled. They’d even swim in the water — and bring its stench back home with them. “We didn’t know what was in there at the time, of course.”

Whatever chemicals and pollutants the water carried, the river was a welcome change to the gang-dominated parks and dangerous streets of that part of town. “As a kid, that was my sanctuary,” Reyes said.

Since taking office in 2001, Reyes has been one of the river’s strongest political advocates, forming the Los Angeles River Ad Hoc Committee and spearheading efforts for revitalization. Like so many others growing up or living near the river, Reyes understands it to be much more than a concrete drainage channel.

But the river of Reyes’ childhood and the river of today are vastly different for one major reason: water. The increased water flow created by the development of the Tillman wastewater treatment facility allowed more plants and wildlife to thrive in the river’s three natural-bottomed areas. All of a sudden, the technically ambiguous river was looking more like a real one.

“The opening of that plant was one of the most significant events in the history of the river,” said Lewis MacAdams, a longtime advocate for revitalization. Shortly afterward, MacAdams started what would become, arguably, an even more important era in the river’s history by creating the advocacy group known as the Friends of the Los Angeles River. A poet, teacher, performance artist and L.A. transplant, MacAdams discovered the river in the early ’80s not long after moving to town and instantly became interested. After a few years of ferment, that interest grew into action when, in the form of an art performance, MacAdams attempted to personify the river and its animal inhabitants in an effort to call attention to its dilapidated state. Almost 30 years later, MacAdams remains the river’s principal evangelist and has been one of the most active participants in efforts for its reimagining.

“I think I was just on a voyage of discovery,” MacAdams said of the early days of his involvement. “There wasn’t anything behind it or any kind of theory, other than maybe just a kind of yin-yang idea that the river was so fucked up that it could only go one way: It could only become less fucked up.”

MacAdams wasn’t the first person to see potential for the river to be reborn. In 1930, eight years before the river was channelized, the eminent landscape and planning firms Olmsted Brothers and Bartholomew and Associates envisioned the river as the connective tissue of a series of parkways that would make up a broader network of green spaces throughout the city. That plan, “Parks, Playgrounds and Beaches for the Los Angeles Region” painted a picture of the Los Angeles basin as a wonderland of parks that appears almost cartoonish as a counterpoint to today’s lack of open space. Despite its comprehensive nature and details on how to fund and implement the vision, the plan was trashed shortly after completion. Though elements of its river-focused parks vision are reemerging today, the plan is seen widely as a missed opportunity and Los Angeles remains one of the most park-poor big cities in the United States.

But the city understands that has to change, and the idea of spending public money on parks is politically viable in 21st-century L.A. In the fall of 2011, Villaraigosa announced a plan to build more than 50 small pocket parks throughout the city over just two years. Only a handful has opened so far, but officials are actively securing sites and beginning construction on more. And in July the city opened a new 12-acre park downtown, hoping to help transition the area into a new cultural hub for the city.

The series of small park spaces opening along the river underscores this trend. The L.A. of the 1930s may have wanted park space as badly as the L.A. of the 2010s, but the political climate today is making even very ambitious projects like the River Revitalization Master Plan appealing to leaders and business people who, 80 years ago, might have turned their noses to such a prospect.

To read more, subscribe to Forefront. Already a subscriber? Click here to continue reading.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)