The idea of bringing manufacturing jobs back to U.S. soil from overseas has become a political force to reckon with. But if the country will never return to its 20th-century heyday as an industrial powerhouse, what can happen at the local level to restore employment in places like Muskegon, Mich., where factories have emptied out and jobs have disappeared? In this week’s Forefront, Michigan-based writer Anna Clark tries to find out if and how “Made in the USA” can ever really return.

Muskegon’s story is familiar. Between the 1960s and 1990, about 18 million Americans were employed in manufacturing. More than a third of that workforce has vanished. The year of Eagle Alloy’s 30th anniversary, 2009, was its worst year, according to Workman. In the heat of the recession, work went down by 80 percent of the average at some points. “We all sacrificed,” said Workman.

But Eagle Alloy made it. In fact, it’s flourished. The scrappy company has a client base from all over the map — food processing, agriculture, mining, oil, gas, drilling, railroads. “Business is very good for us,” said Workman. “We’re running six days a week.” And Eagle Alloy is not the only Muskegon company doing well. With more than 16 percent of the city’s jobs in 2010 in manufacturing, the sector is twice as strong as the national average, according to the Brookings Institution.

“The city has seen a strong comeback in manufacturing,” said Mike Franzak, Muskegon’s assistant planner, in a recent interview. He cited the 423-acre Port City Industrial Park, home to companies that range from toolmakers to textiles. The bid to resurrect manufacturing was so successful, the city has the enviable problem of having more skilled jobs than skilled people to fill them. Electrical engineers are especially coveted. So are welders.

“Schools don’t produce skilled trade [workers] like they used to,” said Workman.

Workman and Cindy Larsen are among the agitators who see manufacturing as the future of cities, rather than the past. On the small scale, this movement is visible in tinkering culture, ignited by Maker Faires in cities around the country like Detroit, Urbana, Ill. and Columbus, Ohio. But it’s also going big, fueled by private and public policy that encourages companies to return outsourced jobs to American soil. In a word, insourcing.

The policy push is paying off. Over a period ending in August 2012, more than 530,000 manufacturing jobs were created — the greatest growth for any 30-month period since 1989. A motley crew of companies is responsible for the jump, including both experimental start-ups and the same industry titans that created factory towns during manufacturing’s 20th-century heyday. Their reasons for insourcing vary, but one theme is constant: It saves money. This is not a movement singularly based on ideology or patriotism, but on economic reality.

“Labor costs in Asia are ticking upward at a time that, for better or worse, American wages stay the same,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “And automation matters more and more, which reduces costs.”

That trend is evident in Columbus, Ga., a city south of Atlanta that for decades watched as employers went out of business or left town. But in 2011, some momentum shifted when Columbus welcomed an ATM and self-service checkout machine manufacturer to town. The NCR Corporation made machines in China, Brazil and Hungary until its leaders realized that moving labor back to domestic shores saved on shipping costs that rise with the price of fuel (each ATM weighs about a ton). Intellectual property was another consideration — the company wanted workers near its engineers, narrowing the possibility for ideas to be leaked.

“We felt like controlling that innovation in-house was critically important,” said Peter Dorsman, NCR’s senior vice president of global operations. The company employs 500 at last count, and expects to hire 370 more by 2014.

“It’s computerized, technological, manufacturing jobs. And those jobs pay very well and make good livings for the families in our community,” Columbus Mayor Teresa Tomlinson told a local TV station last March, when the company opened its second plant.

Meanwhile, the Ford Motor Company has built the Fusion car in Mexico, but announced plans in September to hire 1,200 workers to make the 2013 car in metro Detroit. It’s a significant shift for a car that carries so much of the company’s fortunes with it — the Fusion is Ford’s best-selling vehicle after the F-150 truck. The motivation for the move? Changes in labor contracts passed in 2007 and 2011 had reduced costs. Not to be outdone, GM announced last October that it plans to insource 90 percent of its information technology work, with 1,500 jobs coming to Warren, Mich. in the next four years, and 500 more to Austin, Texas.

In Louisville, Ky., GE Appliances is building a new water heater plant in its massive Appliance Park facility. The new plant will be the first one there in half a century, and it — along with an existing plant that will start making refrigerators — is expected to generate hundreds of skilled manufacturing jobs. The $800 million investment is part of GE’s promise to reinvest in American workers, which has created 15,500 jobs since 2009, according to GE.

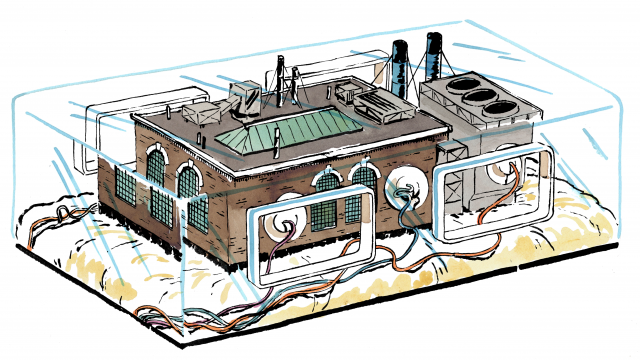

This insourcing revolution is significant for cities, particularly those mid-size urban centers in the Midwest that were forged in the fire of industry — those places like Muskegon. A recent report from Brookings Institution found that 80 percent of all manufacturing jobs and 95 percent of all high-tech manufacturing jobs are now in metropolitan regions, concentrated in the 100 largest metro areas. Because innovation is crucial in manufacturing, companies have an interest in locating near American universities, where engineers and designers can be tapped. The good news for the cities that attract industry is that manufacturing 2.0 jobs are safer and more environmentally conscious than in the past. The bad news is that new industry jobs do not necessarily pay as well as the old ones, particularly since the rise of insourcing hasn’t paralleled a rise in union membership and activity. And for the foreseeable future, despite the profoundly positive changes in 21st-century manufacturing, there simply aren’t enough jobs yet.

To read more, subscribe to Forefront. Already a subscriber? Click here to continue reading.