As I recently wrote in “Cities Are Looking for More Permanent Solutions to Homelessness,” housing advocates across America are working to answer President Obama’s call to end chronic homelessness and make dramatic reductions among other homeless populations.

Amid these nationwide efforts, a decades-old Minneapolis-based design charrette aimed at helping the homeless has found renewed energy for tackling what can often seem like an inexorable problem.

Since 1987, architects, interior designers, landscape architects and students have gathered for the annual weekend-long Search for Shelter Design Charrette, hosted by the Housing Advocacy Committee of the American Institute of Architects Minnesota. They offer pro bono design consultation to local and regional affordable housing and homelessness organizations ranging from women’s shelters to neighborhood associations to the Salvation Army.

There were dozens of Search for Shelter charrettes in cities across U.S. cities in 1987, when the American Institute of Architects launched the event. “In the mid-80s homelessness became something that was very visible,” says Rosemary Dolata, the founder of Concentric Architecture who first participated in the Minneapolis Search for Shelter as a student in the early ‘90s. “There were men on the street in a way that hadn’t been seen before. There were a number of architects nationally who recognized that this was also a design problem that they could contribute to solving.”

Minnesota’s is one of the few chapters remaining that has kept up the tradition. Dolata says that this is due to the continued “deep passion” of the organizers. “Those of us that are leading it up are committed to making sure that it continues, but that also young people come on board and want to be a part of it,” she says.

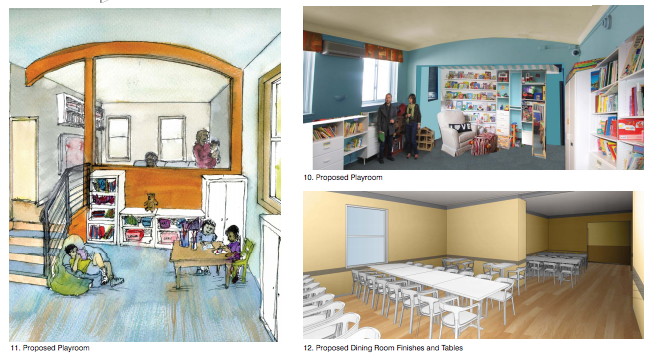

Renderings of recommended renovations for St. Anne’s Place (Credit: American Institute of Architects, Minnesota Housing Advocacy Committee)

The design interventions addressing homelessness have changed since the program started. There is less of a focus on emergency shelter than in the beginning, and more of a focus on durable, long-term housing for the chronically homeless. “There are a lot of people who simply don’t have access to affordable housing and that’s become a status quo — it’s acceptable somehow.” Dolata points to the news that Minnesota recently opened 2,000 spots on its Section 8 waiting list and 36,000 people applied over the span of three days.

“You would somehow have to have the income qualifications to qualify for the affordable housing benefit and be able to be stable enough that in nine years they can call you and you can move in. Where are you the nine years in between?,” she says, pointing out the challenges that she and her local colleagues try to address in the annual event.

The Minneapolis organization Ascension Place has a unique perspective on the charrette: It participated in the very first one in ’87 and once again in 2014. The first design consultation in the ’80s was for a convent building that the organization had acquired.

“They were very influential in those first steps of our ability to take a building from being a convent for religious women to be a family shelter,” says Corein Brown, community outreach and volunteer coordinator for Ascension Place. When the organization was looking to renovate the supportive housing facilities two years ago, Brown says, “It just seemed like a good time to take advantage of professionals that are really passionate about their work.”

Over the course of a weekend last year, Ascension Place representatives met with a design team organized by Search for Shelter, which pointed out ways the building could be re-organized and re-purposed. The team created renderings that showed how storage solutions could be built, walls could be painted, and play and relaxation spaces could be better defined — all within the organization’s budget.

Since the charrette, the organization has enacted many of the team’s suggestions. There is now office space that overlooks one of the playrooms, so that mothers can get work done while monitoring their children. The TV room has been given more of a community feel. “It felt like it was a place that people would come and just zone out,” says Brown “It wasn’t a welcoming space. There were two somewhat worn-out couches and a large TV and that was the gist of the space. Now our TV room has become our health and wellness room.”

There’s still a TV in the space, but it’s less of a focal point. The room has been repainted in brighter warmer colors; there are new couches and new cushy chairs for children. Almost immediately, Brown says, the renovation produced exciting results: “It was really funny, when we got the chairs, kids immediately grabbed books and began sitting in the chairs reading. We were all just laughing, ‘This is what we needed to do to get you guys to read?’ But it’s true. When a space has that calm feeling to it, it encourages calmness in all of us when we’re in that space.”

St. Anne’s health and wellness room after renovations (Credit: Ascension Place)

Dolata explains that in the past four or five years, the Search for Shelter effort has taken on a renewed energy. “There’s been a real effort to look at the quality of design, [which asks the question] ‘How we make sure what we’re creating has a positive design impact on the community?’” She’s hopeful that the program’s upcoming 30th anniversary will once again encourage other communities around the country pick up the charrette as a model for bringing the design and housing communities together to dream up creative solutions to homelessness.

Examples like Ascension Place could be just the thing to generate momentum for the effort. “I think that one thing that could get some attention is the real understanding of what percentage of these people are children,” says Dolata. “I don’t think anyone can blame a child for being homeless.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Alexis Stephens was Next City’s 2014-2015 equitable cities fellow. She’s written about housing, pop culture, global music subcultures, and more for publications like Shelterforce, Rolling Stone, SPIN, and MTV Iggy. She has a B.A. in urban studies from Barnard College and an M.S. in historic preservation from the University of Pennsylvania.