Drivers fighting with pedestrians and bicyclists over road space has become a familiar battle over the last decade. But about 130 miles north of San Francisco, in the small city of Willits, there’s an infrastructure tangle of a different sort playing out.

Planners began drafting the elevated, four-lane Willits Bypass pre-recession, expecting national driving trends to climb and less urban areas like Mendocino County (Willits is at its heart) to grow. Roughly 10 years later their forecasts haven’t materialized, but the $300 million bypass will.

Amid the worst drought record-keepers have ever seen, water has become a galvanizing force for bypass opponents. Willits was placed on a short list of districts likely to actually run out of water earlier this year, and the bypass opposition’s resistance — lawsuits, direct actions and dozens of arrests — centers on the six-mile project’s northern interchange. Now an arid lot sewn with “wick drains,” it used to be a federally protected wetland. Seasonal rains pooled and trickled through valley-wide creeks.

Now, in timing that seems downright ominous, Caltrans’ contractors are draining it to support a freeway.

Like many state DOTs, Caltrans is increasingly the victim of its own attempts to build out of traffic jams. In 2011, the Legislative Analyst’s Office reported that fewer than one-third of the state’s roadways were in good condition, but the transportation agency spent only about 10 percent of its budget on routine maintenance. Most of its money over the last decade has gone to building and expanding, even while existing roadways fall apart.

And California is by no means alone. As federal money dwindles, gas tax revenues fall and state auto-emission caps constrict departments built on Eisenhower-era car-centrism, DOTs are often torn between the future and the past. If they can’t adapt to prioritize existing infrastructure and multi-modal travel, they — like the bypass in Northern California — risk becoming snapshots of another time.

“It’s ridiculous,” says Rich Estabrook, a Mendocino County resident opposed to the project. At his girlfriend Julia Frech’s house, the two display document after state document on a laptop to make their case.

Building Our Way Out of Congestion

California’s Department of Transportation defends this now-controversial bypass with a formula that measures congestion.

“Level of Service” is the term at the heart of their dispute. A two-lane bypass would be less ecologically damaging, they claim, and save around $80 million. But Caltrans won’t build a two-lane alternative because it wouldn’t meet the decided-upon Level of Service, or LOS, which measures a driver’s experience of traffic on a scale of A to F. LOS A is speed and ease; LOS F is gridlock. But because you could get stuck behind a slow-moving car on a two-lane highway, an extra factor can weight smaller projects away from the desired A.

According to the state agency the project needs to be LOS C. LOS D is an operating speed of 40 mph. Estabrook does some back-envelope calculations and estimates that the cutoff for this rural area is one car in either direction every six seconds. He taps the coffee table, counts to six and taps again. It’s a long pause.

At the state capitol 150 miles away, LOS is also under fire. With its lofty dreams of high-speed rail, the Brown Administration continues to draft climate policy that limits auto emissions. And yet the state transportation agency literally measures projects by their ability to encourage high-speed car travel — A to F like high-school grades.

Especially for intersections in cities, LOS disproportionately affects urban infill development.

“The sum result is often to grossly exacerbate the very congestion problem that you’re trying to solve,” says Jeffrey Tumlin of the planning firm Nelson\Nygaard, which has advocated dropping the measure.

It can be replaced with other measures going forward, lawmakers decided in August. But in Willits, as with other projects in the works, the formula still has weight.

According to the agency, although the project forecasted what turned out to be overly optimistic population growth and driving trends, congestion is still the deciding factor. Per a regulatory request, calculations were recently redone. The LOS for a two-lane road, even in the dwindling rural area, was just too low. (Caltrans declined my phone interview request for this story, though it did send along email responses to questions. And a representative of the bypass spoke with me on factual matters.)

Rebuilding DOTs From the Ground Up

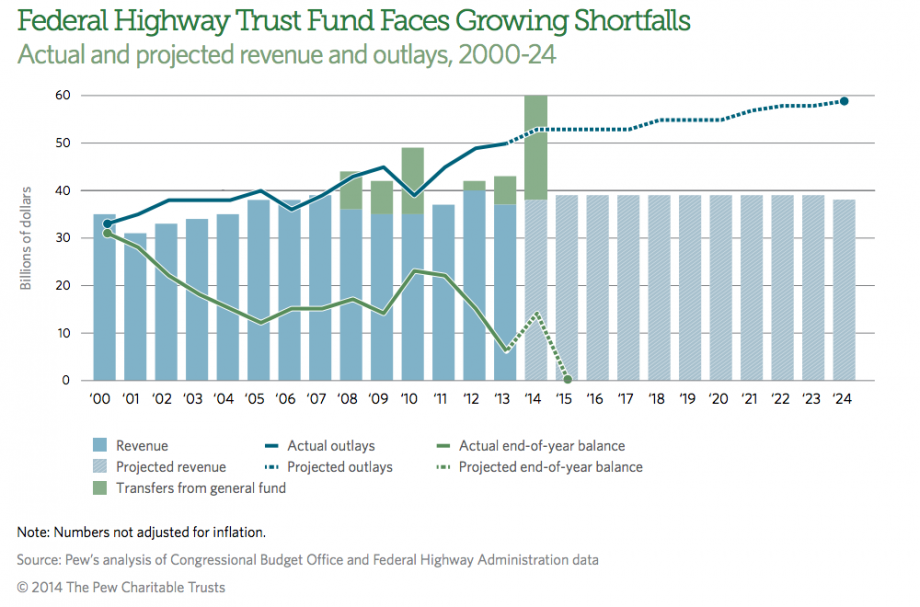

Nationwide, many DOTs embody California’s struggle, thrown into sharp relief as the federal Highway Trust Fund dries up. People are driving less. As climate change worsens, they need to. And yet foundational practices — like LOS — encourage them to drive more.

This institutional priority is shockingly expensive. According to Smart Growth America and Taxpayers for Common Sense, states spent $20.4 billion each year to build and expand their roadways between 2009 and 2011 and only $16.5 billion annually to repair them. New projects made up only about 9,000 lane-miles, meaning that more was spent building 1 percent of the country’s roadways than keeping up the other 99.

Right now, the cost-demand of maintaining the system we already have (including transit) would require about “$13 billion more per year than is already spent at all levels of government,” according to a recent Pew report.

The bleak numbers highlight these agencies’ deep, long-lasting preference for expansion.

“The issue of wanting to build more versus maintain is pretty universal and it’s not surprising,” says Allen Biehler, former secretary of Pennsylvania’s DOT. “After World War II there was a huge increase in auto use — it was the American Dream to have a car and live outside of somewhere. Congestion resulted from all that, and all the civil engineers said ‘this isn’t very much fun.’ So what was the answer? Making it bigger, expanding the road.”

And building is great for political legacies.

“Many analysts argue that we don’t do enough to optimize operations, like coordinated signal timing,” says Brian Taylor, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UCLA, “but it’s very hard to cut a ribbon in front of a new computer.”

When Biehler was appointed in 2003, the department, then updating its capital improvement program, had 26 expansion projects totaling about $5 billion.

“But we were really in a dangerous position from a structural standpoint,” he recalls. Switching into maintenance mode wasn’t the most attractive option; it was the only one available.

Culturally, the agency was tiptoeing into uncharted territory. DOTs expand roads — to veer off that course required rebuilding the institution from the ground up: rewriting design manuals, re-thinking land use and forming partnerships with other agencies.

“In the civil engineering and transportation world, all of us are taught to understand certain practices,” he says. “We had to take the time out to ask ‘Are these the right ones?’”

Culture Change at DOTs

Clearly something needs to change — soon. And DOTs in Oregon, Washington, North Carolina, Michigan and Massachusetts are all shifting gears according to Karina Ricks, also with Nelson\Nygaard.

Paul Mather, a spokesperson for Oregon, says that becoming a “build better” organization hasn’t been too painful for the state because it’s long been constricted by funds.

“We’re a small state population-wise and a large state in terms of land mass so we have a lot of highways and not a lot of revenue generated to take care of those roadways,” he says.

The DOT’s funding priorities (preserving vs. enhancing) are decided by an outside organization, the Oregon Transportation Commission. Meanwhile, regional commissions give input on projects most important to each geographic area — regardless of whether they’re highways, transit or bike/ped — and the agency applies for funding accordingly, which Mather says keeps it from being segregated into various modal “silos.”

Massachusetts, meanwhile, rewrote its design manual in 2006 to prioritize smart growth. The process, Assistant Chief Engineer Thomas DiPaolo recalls, became a priority under then-governor Mitt Romney. Internally it began when community input on a counterintuitive notion starting trickling in: The agency’s roads were too wide.

“We starting thinking about how our design standards affect the communities around us,” he says. Ultimately, they asked a deeper question: How can DOTs influence land use?

Formally, 28 people with backgrounds ranging from bicycle and planning to historic commissions are listed at the beginning of the new guidebook. But DiPaolo, who was part of the process, puts it more simply: “There were a lot of people in the room.”

Big-picture, inter-agency meetings like those in Massachusetts need to happen, institutionally challenging though they may be. A report called “The Innovative DOT” compiles a list of ideas, from public-private partnerships to mode-neutral funding strategies. It’s a brainstorm in the works — meant to be periodically updated — and also completely daunting.

Fixing long-entrenched practices, it states, requires “initiating a culture change throughout.”

DOTs of the Future

Innovation can still emerge from California’s high-speed wreckage. One of the organizations responsible for the DOT handbook, called the State Smart Transportation Initiative, also released a scathing report on Caltrans earlier this year. But the agency is responding, at least according to its website. A detailed map shows a “strategic direction group” overseeing what resembles the ground-up remake other departments have embraced.

According to the agency’s email response, it’s also trying to adopt what it calls a “fix it first” philosophy. Increased oversight is coming from an organization called CalSTA, formed by Jerry Brown.

And as a writer for Streetsblog gleefully put it in August: “Ding dong … LOS is dead.”

California’s climate is changing. Outdated projects continue, but hopefully, over time, Caltrans will adapt.

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)