This Friday, at the UN conference in Lima, delegates will discuss yet again how their countries might finally reach an agreement to address climate change. But one presentation, by scientists from the US government and Arizona State University, will focus not on countries but on cities, showcasing efforts to rigorously measure urban greenhouse gas emissions.

Their participation is part of a growing push to include cities more prominently in international discussions on global warming. At the climate summit in New York in September, a “compact of mayors” brought together more than 2,000 cities in a commitment to specific targets and strategies. Cities are taking the lead in part because of paralysis at the national and international levels, but also simply because cities are responsible for the vast majority of emissions — about 70 percent of the total, despite taking up only about 2 percent of the land.

But for cities to really be able to rein in their emissions — and to prove that they’re doing so — it’s critical for them to be able to measure and monitor them. That’s where Friday’s presentation — a joint effort by entities including the Hestia Project at ASU and the Megacities Carbon Project — comes in.

The Hestia Project is attempting to analyze datasets at a very high spatial and temporal resolution. Starting with Indianapolis, lead researcher Kevin Gurney and his colleagues collected prodigious amounts of data in two main categories: vehicles and buildings. Their sources ranged from tax documents to the Department of Energy to the Federal Highway Administration. The process is “tedious and it’s lengthy,” says Gurney. “We got pretty good at it.” Their reward was hourly estimates of carbon dioxide emissions. They have now also completed analysis of Salt Lake City, and are working on Phoenix and Los Angeles.

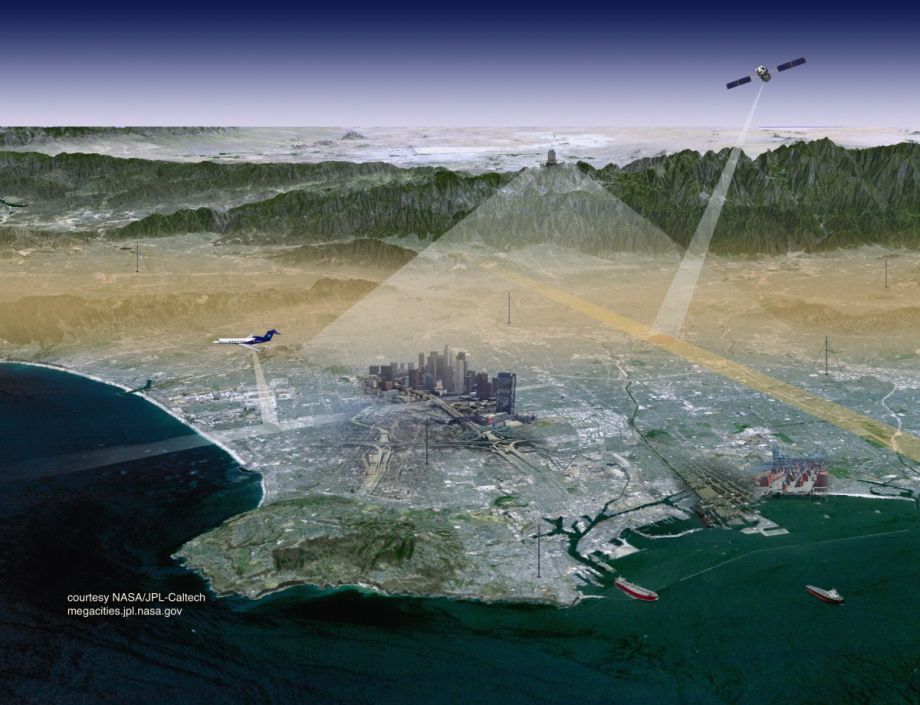

Meanwhile, Gurney’s collaborators are studying emissions from a different vantage. Using instruments installed in cell towers, as well as small aircraft flying over the cities, among other tools, they are trying to monitor the actual carbon dioxide and methane in the urban air. They will then compare their results with the Hestia numbers. (In Indianapolis, so far, the correspondence has been fairly close.) These two kinds of complementary data will, the thinking goes, provide cities with a much finer-grained picture of their emissions than was previously attainable.

One of the goals is to provide individual city governments with insights into how to most efficiently invest in emissions reductions. For example, in Salt Lake City, Gurney’s research found that a mere three road segments accounted for 40 percent of on-road CO2 emissions. They also found that mobile homes, which tend to be poorly insulated, were a surprisingly large source of emissions. One possible remedy: The city could consider offering free or subsidized insulation to low-income mobile home residents.

According to Gurney, most cities are looking for ways to reduce emissions that will also entail other payoffs. “Look, Kevin,” they ask him, “What can you tell us where it becomes that tie-breaker? That additional co-benefit that pushes us to doing something rather than not doing something?” The Hestia Project is planning a meeting next April in Indianapolis, where they will discuss policy ideas with city leaders and local environmental NGOs.

But beyond the isolated actions of cities, the more ambitious vision is to establish a global network of cities that can develop the methodology, share data and best practices, and ultimately form a framework for slashing emissions worldwide.

“My gut feeling is we could be within five and 10 years away from having a global system running,” says Riley Duren, a NASA engineer at the Megacities Carbon Project.

The Megacities Carbon Project uses remote sensors, aircraft and satellites to measure greenhouse gases in L.A. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

There are certainly formidable barriers to achieving that goal. The “bottom-up” data from government administrative records can be a headache to access and analyze in the United States, but it’s nearly nonexistent in many developing countries. And the “top-down” approach of gathering atmospheric data faces a number of scientific hurdles. One is distinguishing the CO2 and methane generated by fossil fuels from naturally occurring gases. Another is that the trajectory of gases varies by city. In Indianapolis, which is flat, wind blows pollutants away relatively quickly. The topography of Los Angeles, by contrast, tends to trap pollutants in the air. The techniques for measuring emissions need to take those differences into account.

But significant progress has already occurred in the past few years, and interest is growing. According to Duren, four years ago, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, there were talks on urban carbon monitoring for the first time — three of them. This year, there will be more than 100 talks from over 20 cities.

More people are starting to realize that focusing measurement efforts on cities makes sense — both because cities are the major drivers and because monitoring them is comparatively feasible. As Duren puts it, “This is kind of corny, but I like to say it’s like looking for your keys under the streetlight. But in this case it happens to be true that most of your keys are under the streetlight.”

The Science of Cities column is made possible with the support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow was Next City’s Science of Cities columnist in 2014. She has also written for the New York Times, Slate and Dissent, among other publications.