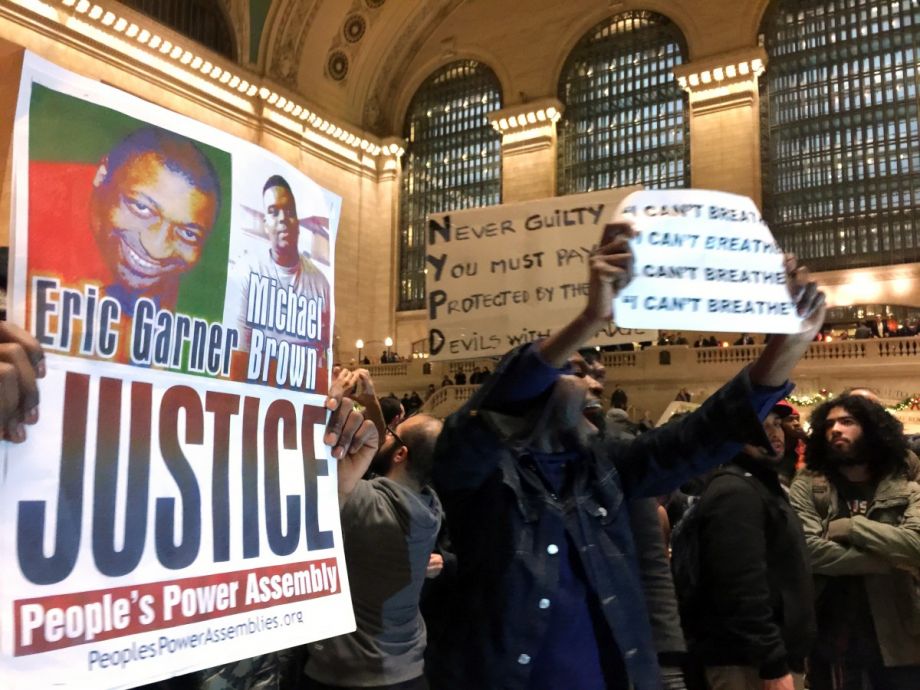

Yesterday, a grand jury refused to indict a member of the NYPD for asphyxiating asthmatic suspect Eric Garner in July with a “chokehold” maneuver banned by his department. In the past two weeks, a police officer in Cleveland whose record reflected he had “dismal” handgun skills gunned down a 12-year-old holding a BB gun in a Cleveland park, and autopsy results showed that a mentally ill man shot 14 times by a police officer in Milwaukee was hit in the back. In all three cases the police officer involved was white while the suspect was black.

These deaths once again press the need to address the way officers engage the public at large, and public mistrust that results from such examples is one of the reasons some police departments, from Washington state to Chicago, are making an effort to put “protect and serve” back at the forefront of policing. Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey might want to look to how both are taking the lead. Earlier this week, President Obama appointed Ramsey head of a national Task Force on 21st Century Policing, as part of an initiative to address the breakdown in police-community relations that has taken over the public dialogue since the August shooting of 18-year-old Mike Brown by an officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

In an interview with the Associated Press, Chief Ramsey called the task ahead of him “daunting, but … doable.”

Revising Police Training

In 2012, Chicago tapped a team of Yale criminologists to remodel its officer training program under a mandate from Police Superintendent Garry F. McCarthy. By January 2014, more than 8,000 Police Academy graduates had been schooled in the new curriculum — which teaches officers to be responsive, impartial, respectful and fair.

Proponents of the strategy say it not only reduces tensions between police and the community, but improves public safety by making citizens more likely to obey laws and cooperate with police.

Members of Chicago’s Police Education and Training Division spent the spring and summer retraining officers in the California cities of Salinas, Oakland and Stockton and are now fanning out to other municipalities to share what they learned.

Exactly one year after Chicago finalized its new curriculum, Washington graduated its first class of police recruits through a radically modified officer training program. The goal is to put police on the street who can navigate tense situations with empathy while respecting the impact their actions have on how situations unfold.

The training strategy is the brainchild of Sue Rahr, who left her job as sheriff of King County to take over as head of the Washington State Criminal Justice Training Commission in 2012. David Bales, Rahr’s deputy, says the program dispenses with military-style boot-camp elements common to many police academies in favor of coursework focused on communication and conflict resolution. In addition to traditional training in firearms and takedown techniques, recruits take courses in behavioral psychology and are encouraged to talk problems out rather than simply respond to barked orders.

“We are guided by the underlying goal of producing officers who are guardians as opposed to warriors,” says Bales, who himself has more than three decades of law enforcement experience.

“The most common corresponding emotion to fear is anger, and anger does not facilitate ongoing compliance,” he adds. “We teach recruits that when they mistreat people they actually may make that person more dangerous.”

The program is hardly a cakewalk. In one exercise, described in an article published last year in the Seattle Times, recruits are doused twice in the face with pepper spray and asked to complete a series of tasks that frequently includes reciting the federal and state statutes governing the use of force.

Bales says the purpose of the exercise is to demonstrate to officers that they can focus, think, problem solve, defend themselves and even deescalate while under extreme duress.

“When an officer has confidence in their abilities, they are less likely to overreact out of fear,” he says.

Unintended Consequences

Despite a pronounced drop in crime, technological improvements in policing and the increased professionalism of law enforcement, surveys show that “trust and confidence” in police has remained relatively unchanged (averaging about 50 percent) for four decades. New polling from Gallup shows that whites are significantly more likely to express trust in police than blacks.

At least part of the problem can be viewed as an unintended consequence of the war on drugs — which turned entire communities into de facto battlefields and a generation of young men of color into potential enemy combatants.

Reining in police militarization (another goal of the Obama administration’s new proposal) is a vital first step to repairing the damage. But even the most deadly weapon is just a mindless tool. It’s the attitude and character of the police officer holding it that matters.

In a statement provided to Next City, Chief Ramsey acknowledged the importance of officer behavior in informing the overall tone of police-community relations: “We as police departments have an obligation to build public trust and that starts with transparent behavior and developing police legitimacy across the board.”

A report released last March by the Police Executive Research Forum, which Ramsey heads, also highlighted the critical role police “legitimacy” and the related concept of “procedural justice” play in effective law enforcement. The latter concept refers to the belief, supported by decades of scholarly research, that processes that are perceived to be fair are the most likely to generate favorable outcomes.

Criminologists such as Yale’s Tom Tyler, who has spent decades studying the effect of officer behavior on law abidance, have found that citizens are more likely to gauge their interactions with police based on the perceived fairness of law enforcement rather than its effectiveness or lawfulness.

“The issue of interpersonal treatment consistently emerges as a key factor in reactions to dealings with legal authorities,” Tyler writes. “[P]eople focus on cues that communicate information about the intentions and character of the legal authorities with whom they are dealing.”

For instance, he cites studies that suggest members of minority groups factor how they are treated by police into determining whether they have been racially profiled. (This helps explain why policies like stop-and-frisk tend to be counterproductive).

Fewer Deadly Encounters

It hardly needs to be said that not shooting people who don’t deserve to be shot is a crucial piece of the police legitimacy puzzle. Calling a shooting justified is not the same thing as calling it necessary; this has led some departments to rethink the way they train their officers in the use of deadly force.

Following the police shooting in Albuquerque last March of homeless camper James Boyd, the New Mexico Law Enforcement Academy began instructing officers to take cover and consider their options instead of immediately engaging aggressive suspects.

Two months earlier, Dallas Police Chief David O. Brown issued changes to the department’s use-of-force program to require training once every quarter instead of bi-annually.

In the wake of the Mike Brown shooting, one city, Richmond, California, emerged as the poster child for the police reform movement for going five years without a single fatal shooting by its officers despite the city’s long history of violent crime. Richmond Police Chief Chris Magnus credits the achievement to the expanded use of non-lethal weapons and monthly firearms training focused on accuracy and accountability.

Over the last five years, the Richmond PD has expended just eight bullets on five people. That’s nearly as many bullets that Officer Darren Wilson fired into Mike Brown. (It’s worth noting that Wilson’s grand jury testimony also suggests that Ferguson police are given the discretion over whether to carry non-lethal weapons such as Tasers.)

On September 14th, Richmond experienced its first fatal officer involved shooting since 2007, to which the city responded with two separate investigations and a concerted community outreach effort. Both the police chief and his deputy attended the victim’s funeral in civilian clothes to avoid provocation.

Chief Magnus’s ability to think empathetically about his impact on the community he serves has won him high praise both inside and outside of Richmond. In September, he was summoned to Ferguson as one of two law enforcement experts tapped by the DOJ to review civil rights charges in connection with the Mike Brown killing.

As they move forward with their mission it’s fair to say the members of the President’s new trust-building task force can learn a lot from the experiences of forward-thinking leaders like Magnus.

The Washington State Criminal Justice Training Commission is now working with Seattle University to gauge if the department’s new empathy training is having its intended effect. Deputy Director Bales says that while it may be too soon for any concrete evidence, there’s no doubt in his mind that he is helping put better, more responsive police officers of the streets of his state.

“Empathy connects us to people, makes us better crisis interventionists, better investigators, better public servants and healthier, happier people,” he says. “Could it be a national model? I don’t know, but we will enthusiastically contribute to the discussion and the development of best practice in any way we can.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Christopher Moraff writes on politics, civil liberties and criminal justice policy for a number of media outlets. He is a reporting fellow at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a frequent contributor to Next City and The Daily Beast.

Follow Christopher .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)