When Amazon announced its HQ2 RFP last year — asking cities up-front how they would offset the $5 billion investment — officials found themselves trapped in what Brookings calls a “classic prisoner’s dilemma.”

“They know that they would all be better off simply competing on their natural advantages, not by offering incentives,” a new report from the institute theorizes. “But because many cities will use incentives, all feel they must.”

And Amazon is only the tip of the corporate welfare iceberg, Joseph Parilla and Sifan Liu conclude in “Examining the Local Value of Economic Development.” Driven partially by a political climate that rewards legacy-building (i.e., the ribbon-cutting effect) and partially by an economy that’s stagnated for the bottom 50 percent of earners, corporate subsidies have become a big business in U.S. cities, costing the public somewhere between $45 and $90 billion in 2015.

But while most of the academic literature that exists finds that such incentives don’t always create more jobs (particularly jobs targeted at the communities most in need), the Brookings paper takes an aspirational approach. How could incentivizing certain businesses work for cities — even if it doesn’t always work now? Using transactional-level data from four cities over five years (Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Salt Lake City and San Diego), the paper outlines how the public sector can target incentives based on several core principles of so-called “inclusive economic development.”

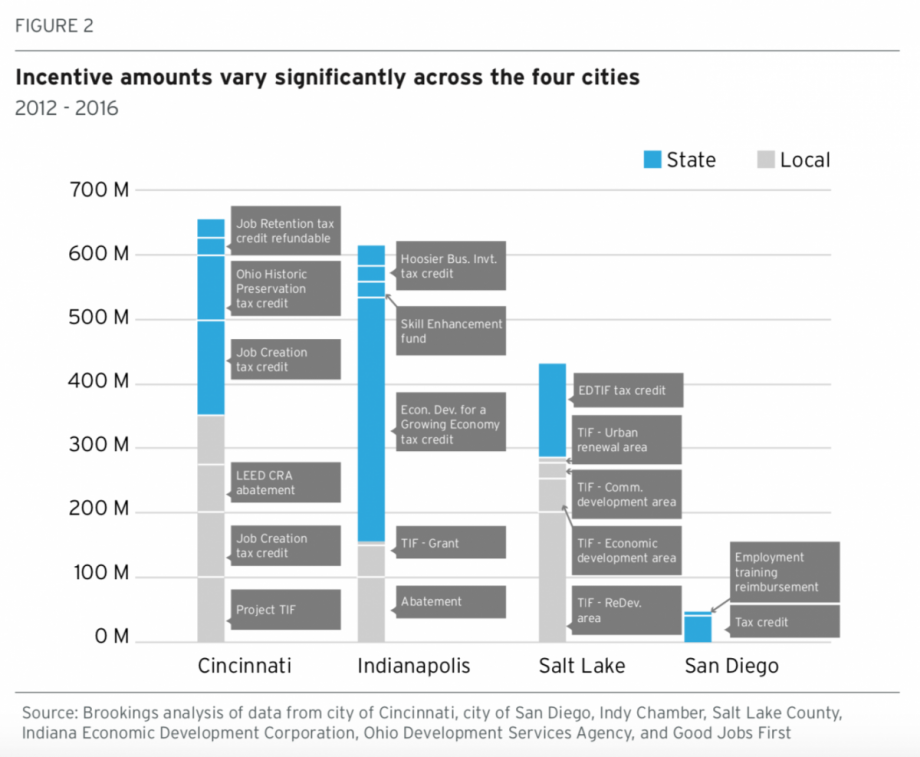

The four cities are, of course, very different — both in their history (manufacturing shaped the midwestern cities, unlike their southwest counterparts) and their preferred method of incentivizing industry. Salt Lake City officials prefer tax increment financing (TIF) programs; Leaders in San Diego and Cincinnati spring for tax credits; and Indianapolis politicos tend to like a mix of TIFs and abatements.

(Credit: Brookings)

Still, researchers were able to outline four key principles cities could work with to further the end-goal of such incentives, and measure how each municipality aligned with those principles.

The principles include:

- “Grow from within” by prioritizing firms in advanced industries that drive local comparative advantage and wage gains.

- “Boost trade” by facilitating export growth and trade with other U.S. and global markets in ways that “deepen regional industry specializations and bring in new income and investment.”

- “Invest in people and skills” by “incorporating workers’ skill development as a priority for economic development.”

- “Connect place” by syncing up local communities with regional jobs and housing.

The cities’ alignment with those principles varied. All four invested heavily in export-related industry.

“The export intensity of industries that receive economic development incentives — that is, the share of local output accounted for by goods and services exports — across the four cities is more than twice as high (25 percent) as the economy as a whole (11 percent),” the paper concludes.

But that last principle is decidedly lacking in several of the municipalities.

From the report:

Many cities focus incentives on addressing blight and distress in communities of concentrated poverty. Cincinnati and Salt Lake clearly display this focus, but it is less apparent in Indianapolis and San Diego. The average poverty rate of a neighborhood in which a business or redevelopment receives incentives is nearly 30 percent in Cincinnati and 18 percent in Salt Lake, compared to jurisdiction-wide poverty rates of 18 percent and 12 percent, respectively.

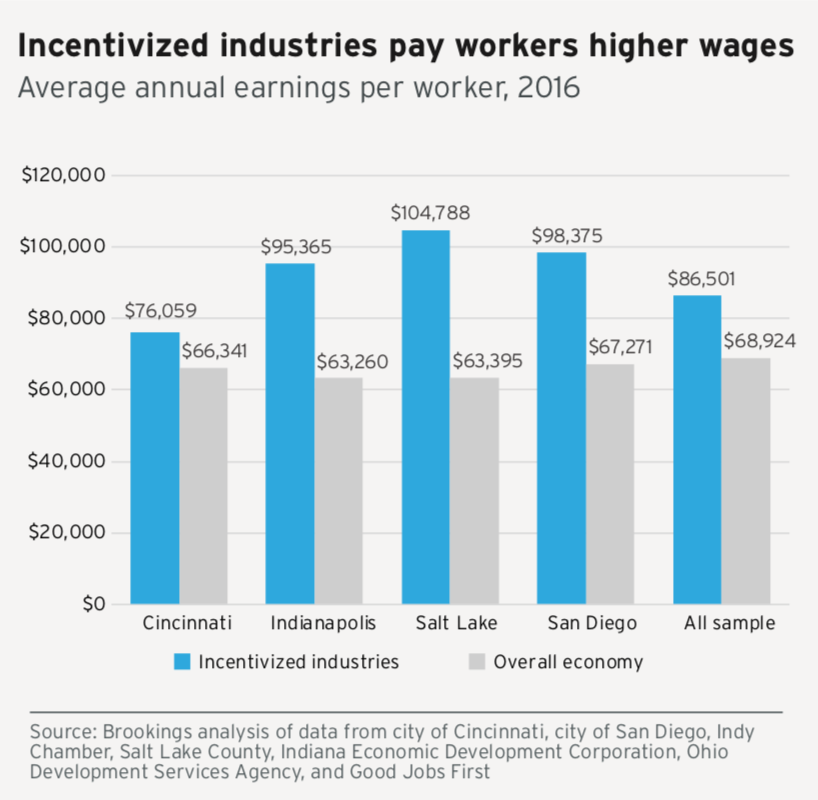

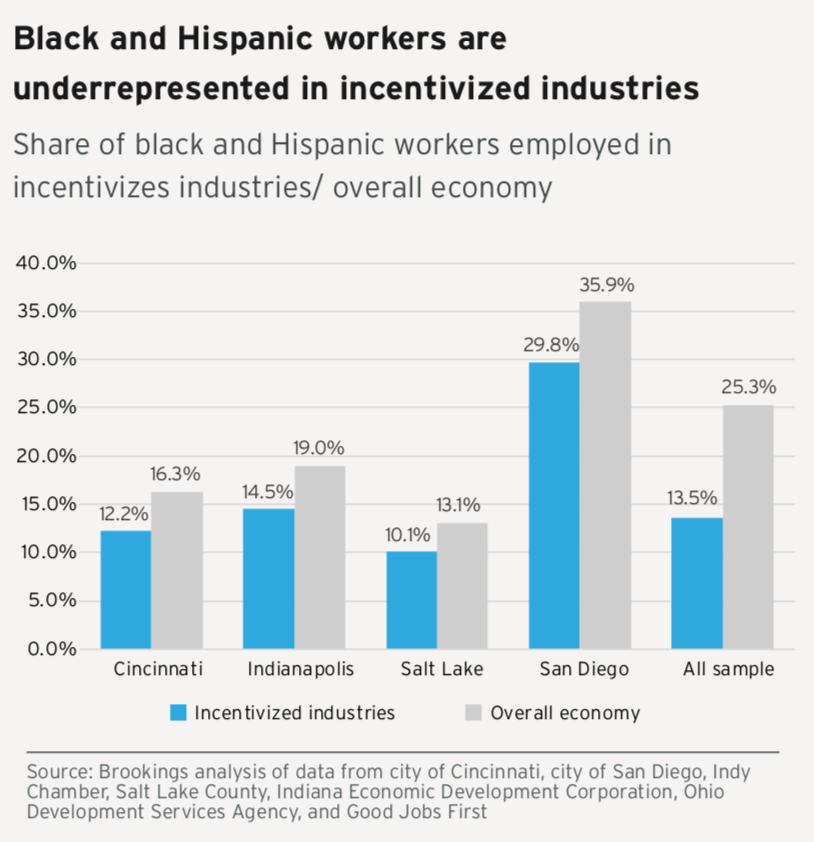

And while the incentivized industries generally paid their workers more, black and Hispanic workers were under-represented in those industries, furthering regional inequality across all four metros.

(Credit: Brookings)

(Credit: Brookings)

One final takeaway from the report, which Next City has also covered: City leaders need to be more transparent about the public funds they’re giving to private companies.

“Localities must commit to making incentives information publicly transparent,” Parilla and Liu said in a statement. “And then rigorously evaluate their impact on firm outcomes to determine what works.”

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)