Klaus Jacob has developed a reputation as New York City’s storm-surge sage. A seismologist by training, he spent the first decades of his 45-year career as a researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, where he now holds the titles of special research scientist and adjunct professor.

In the 1990s, Jacob and his colleagues ran a five-year, FEMA-backed study to estimate the consequences of a major earthquake in New York City. In the early 2000s, they were asked to run a similar study, but for hurricanes and sea-level rise. The resulting figures have not only proved alarmingly accurate, but have also found their way into policy documents that inform city, state and regional planning, as well as major infrastructure projects, billion-dollar developments and almost every informed conversation on the future of the five boroughs.

I spoke with Jacob a few days after Bill de Blasio became the 109th mayor of New York. (This conversation has been edited for publication.)

Next City: What’s Mayor de Blasio’s first move when it comes to climate change and sea-level rise?

Klaus Jacob: Mayor de Blasio needs to make a decision about where he wants to place climate change, sea-level rise, storm preparedness and resiliency in his priorities. [Former mayor Michael] Bloomberg had them relatively high, but he also had a specific preference for implementation that de Blasio might rethink.

NC: What do you mean?

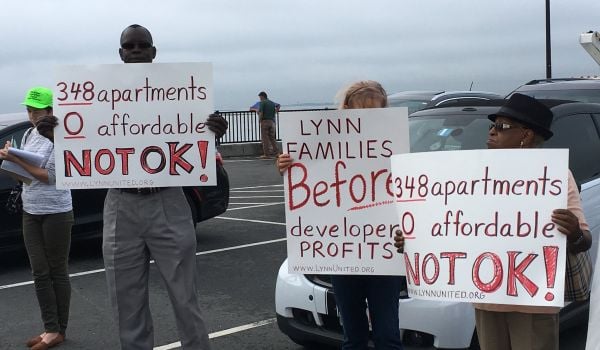

Jacob: For example, one project in Bloomberg’s ambitious SIRR report was Seaport City, as they called it. That would be a new development on Manhattan’s East River waterfront that was sold to the public as a potential protective structure, but it is essentially another luxury building complex. My guess is that when de Blasio looks at his overall agenda, possibly affordable housing and maybe public housing could be a priority. And he may see that another luxury neighborhood on the water might not be the most important project.

Personally, I don’t think we should continue our bad land-use policy of putting valuable assets right on the waterfront where they are exposed to risk. That was justified when we had a dilapidated waterfront and considered only urban renewal. But that was done and planned as renewal without knowing that sea-level rise and climate change would create risks for these kinds of projects.

Given that situation, I think de Blasio has a bad legacy to take care of. We have a sense of past waterfront developments, but now we need to change into sustainably resilient development.

NC: That’s a tall order. Where can he start?

Jacob: If affordable housing and public housing are a priority, why not use the pressures facing New York City as an opportunity? There are neighborhoods in the city – the Rockaways, Red Hook, parts of Staten Island – that may not be sustainable in 100 years, even with a lot of effort. And a lot of those communities have a lot of public housing that offer a questionable quality of life. What if we took this opportunity to reinvent some of our public housing stock and to ensure their sustainability in the long term? That’s the kind of project where a mayor could set the future on a certain course. It would create an incredible legacy.

NC: What else is on your list for the new mayor?

Jacob: A great deal of our infrastructure is at risk, but that’s not entirely in his purview. What he can do is push the governor and the legislature to not just fix what happened, but to make us resilient.

If I had one priority, it would be thinking long-term. Short is a few years, medium is 2030, long is out past 2050. We need to think even further. We need to build infrastructure that is going to be around in 2100, otherwise it is wasted money. We should not be in the business of creating problems for future generations.

In the long run, this is the priority. It’s not understood that way because there are always shorter-term issues that rank higher, and maybe justifiably so. The things that I’m talking about, though, if we don’t take care of them, they will undermine the economic viability of the city. Many of the areas that were submerged during Sandy will be permanently underwater by the end of the century. That means all of the infrastructure and all of the buildings will have to be waterproofed. We will not just have yellow taxis, but yellow taxi boats. These are the issues, and we are in denial.

So which mayor will start doing the right things? Bloomberg was good at making noise about it, and he did a lot of good things. Roofs and hybrid buses and a million trees, that’s all fine and good, but it avoids the tough questions: what do we do with businesses and housing and infrastructure on the waterfront? We have hundreds of billions of dollars exposed to very serious risk that we can’t postpone.

A mayor can set us on track to stretch out the inevitable transformation, or he can ignore the problems and force future generations to act in haste.

NC: What would acting in haste look like?

Jacob: Barriers to seal off the harbor is one. Ultimately sea-level rise makes those untenable, because you have to balance the Hudson and Raritan rivers. You can keep storms out, but not the permanent rising of up to six feet that’s predicted by end of century. That will make barriers an incredibly expensive stopgap.

We need to look at high terrain as the places we should build for our livelihoods, sustainability and economy. We can turn waterfront into parks. Maybe only in the most important areas like Wall Street and downtown, where too much money is already invested, will we actually abandon the lower floors and simply move upwards. That’s how we have to start thinking.

NC: That’s a terrifying future.

Jacob: Yes, maybe, but when you write it, don’t make it sound frightening. I think there are wonderful opportunities to make this a better city. Climate change allows us to think big and great thoughts.

Graham T. Beck has written about art, cities and the environment for the New York Times, The Believer, frieze and other august publications. He’s a contributing writer for The Morning News and editor-in-chief of Transportation Alternatives’ quarterly magazine, Reclaim. He lives in New York City and tweets @g_t_b