Bumbling, willfully ignorant and (apparently) crack-smoking Mayor Rob Ford seems a poor poster child for a city of Toronto’s stature. Allegations of Ford’s drug abuse are just the tip of an iceberg of ethics violations, bad-faith negotiating, homophobia, transportation planning idiocy, casino boosterism and sexual harassment that don’t comport with Toronto’s importance in Canada and in the global economy.

But Ford’s unwillingness or inability to come to grips with Toronto as a global city is not unique. In fact, as in the U.S., persistent urbanization over the last century has not translated into a political culture in Canada that respects, let alone listens to, its cities.

Shawn Micallef, who details Toronto’s nooks and crannies for the Toronto Star, told me this winter that Toronto “is still coming to terms with itself as a global city.” I heard something similar from Roger Keil, director of the City Institute at York University in Toronto, who told me about the “notion of Canada as a rural country” and how its “urbanity has to be constructed.”

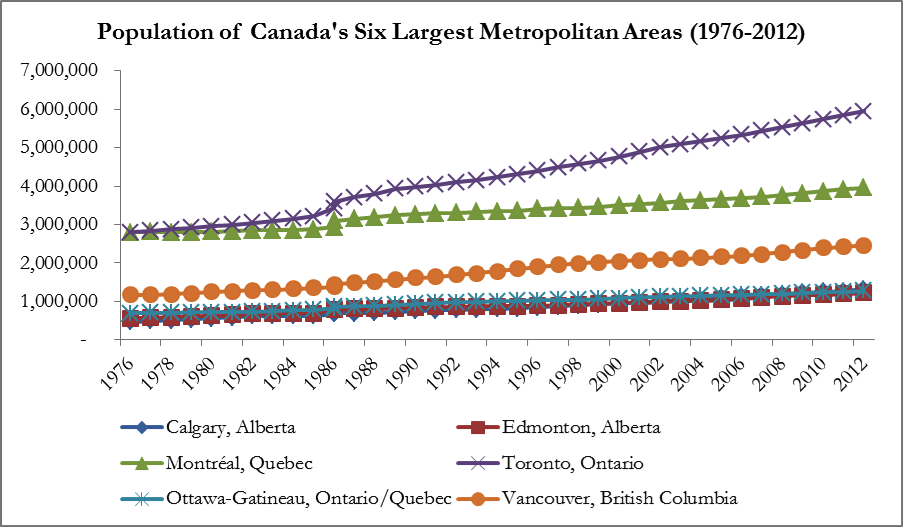

This sentiment is somewhat strange to hear, given Toronto’s outsize demographic and economic importance in Canada. In 2011, according to Statistics Canada, the population of the Toronto metropolitan area was 5,584,064 — almost 17 percent of Canada’s population. The metro population jumped 9.2 percent between 2006 and 2011, a figure impressive on its own until you realize that this represented fully 25 percent of the entire country’s population growth during that period. The city itself grew at a brisk 4.5 percent, though growth at the national level was faster.

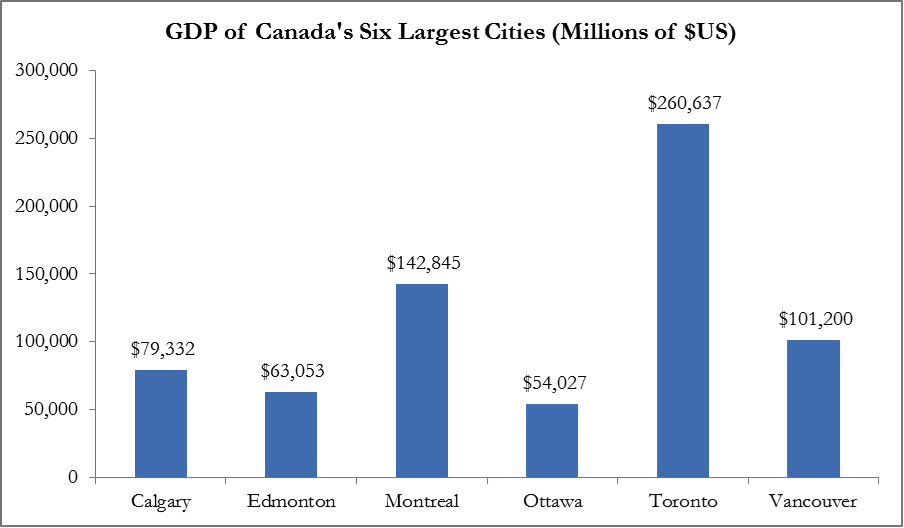

Toronto is also Canada’s economic heavyweight. With a 2012 metropolitan GDP of $260 billion, it nearly doubled the economic output of its nearest competitor, Montréal, and represents almost 40 percent of the combined output of Canada’s six largest metros. While other metros play even larger roles in their provincial economies, Toronto is responsible for close to half of Ontario’s output. In 2010, the Toronto metro was responsible for 22.5 percent of the national GDP. By comparison, that year New York’s monstrous output of around $1 trillion accounted for only 8.5 percent of the U.S. GDP.

Source: Brookings Institution Metro Monitor

One of the most interesting aspects of Toronto’s outsize influence is that until the 1970s, Montréal was Canada’s workhorse metro. But political instability in Québec and a particularly permissive attitude toward immigrants (and American draft dodgers) in Toronto helped the Ontario city outpace its Québécois rival. In fact, foreign-born individuals made up 45.7 percent of the Toronto metro population in 2006: that is, nearly half of the people living in the Toronto metropolitan area were born outside Canada.

Source: Statistics Canada

One explanation for the lack of appreciation of Toronto’s importance to Canada is the treatment of cities in the Canadian constitution.

As a domestic policy adviser to President Ronald Reagan once remarked to a group of mayors, “It’s our view that cities are not mentioned in the Constitution.” This is, strictly speaking, true. But in reality, the U.S. federal government interacts directly with cities in ways large and small, from transportation grants to community development. In Canada, in contrast, the federal government is much more constrained.

The Canadian constitution provides provincial legislatures — Ontario, in Toronto’s case — with exclusive authority for municipalities. New York City may have to beg state legislators in Albany to allow it to, say, increase taxes on the wealthy, but no one in Albany complains too loudly when Washington sends money directly to New York City. In Canada, however, city efforts to attract federal money, or even federal attention, are constrained by concerns about a power struggle with the provinces.

The place of cities in Canada’s constitution is largely a result of the country’s economic roots in agriculture, mining and forestry. As Keil put it, Canada’s constitution was “rural.” Indeed, in the Constitution Act of 1867, “Municipal Institutions” are sandwiched between “Hospitals, Asylums, Charities, and Eleemosynary Institutions” and “Shop, Saloon, Tavern, Auctioneer, and other Licenses” in the enumeration of exclusive powers granted to the provinces.

For much of Canadian history, the consequence has been that cities like Toronto have not played a very prominent role in national politics. John Sewell, a Toronto political activist who was mayor from 1978 to 1980, told me that, “Usually, the federal government follows the province.”

Ford’s predecessor as mayor, David Miller, tried hard to change this. Miller is charismatic and articulate — he once asked me whether I would prefer his responses to my questions in the form of sentences or paragraphs — and he drove hard for a so-called New Deal for Cities that aimed to bring Toronto (and other Canadian cities, but especially Toronto) money, power and a seat at provincial and federal negotiating tables.

The results of Miller’s campaign were respectable. The federal government pledged to share gas tax revenue with Toronto and other municipalities beginning in 2005 and agreed to a sales tax rebate. The feds also agreed to funding commitments for capital costs of the Toronto Transit Commission. A new City of Toronto Act expanded the tools available to Toronto to raise revenue. Annual transfers from the federal and provincial governments due to these New Deal initiatives were estimated to be more than $500 million in 2009-2010. Federal infrastructure investment, which was the overwhelming beneficiary of the new initiatives, spiked significantly in 2004 and has remained high since.

But even with these achievements, the New Deal was only a partial victory for cities at the federal level. Enid Slack, director of the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance at the University of Toronto, likes to remind people that what was originally known as the New Deal for Cities eventually came to be called the New Deal for Cities and Communities, illustrating the “peanut butter” — spread it around and spread it thin — approach that characterizes efforts to direct money to urban areas. Canada’s current Prime Minister Stephen Harper has completely abandoned the New Deal campaign and pursued an approach to federalism that favors strong provinces and less intergovernmental engagement.

Some people point out that Harper has maintained much of the infrastructure spending begun in the New Deal. Gas tax sharing, for example, will provide Ontario with nearly $3 billion between 2010 and 2014. Anne Golden, formerly the head of Canada’s Conference Board and an influential voice in Toronto urban affairs, said that Harper “did not undo what Mr. Martin did.” But others find this to be insufficient. Sewell said Harper has “no interest” in cities. Keil conceded that Harper has not done anything bad to cities, but found it “amazing that the federal government has not done more.”

Toronto’s recent history is quite a positive one. The city earns high marks on a handful of livability and economic competitiveness indices. Spurned in previous Olympic bids, the city will hold the 2015 Pan American Games. Earlier this year, Toronto even edged out Chicago as North America’s fourth largest city.

But institutional impediments to federal urban policy in Canada’s constitution, and the impermanence and uncertain gains of Miller’s New Deal for Cities, suggest that the saga of Rob Ford is less a deviation from a relentless march toward a better Toronto, better cities and better urban policy than a reminder that, despite persistent urbanization, there is nothing inevitable about the urbanization of politics. In Canada, as in the U.S., longstanding institutions and shifting political climates mean policymaking for cities is a contingent, context-specific endeavor that can, but needn’t always, succeed.

As Keil reminded me, less-urbanized, natural resource-rich provinces like Newfoundland and Saskatchewan are booming. Their interests will need to be looked after, too.