Here’s an easy way to increase robust job growth in your city: Don’t increase the cost of working for employers. Philadelphia is facing this dilemma right now. But how to grow the tax base while simultaneously reducing taxes for business owners?

It’s simple. Tax what can’t move easily to cheaper areas — the land. New research from Center City District and the Central Philadelphia Development Corporation, a quasi-public joint business improvement district and community development corporation, explores Philadelphia’s regional job loss over the years, as well as ways to fix what ails it. From the study:

By taxing what can readily move to suburban locations (jobs and businesses) rather than immobile assets (land and buildings), Philadelphia increases the cost of working and locating a firm in the city. This drives down office rents, weakens demand for all commercial space, discourages business growth and reduces the share of real estate taxes local government derives from business properties across the city.

Basically, higher taxes on employers give them a reason to think about moving outside city limits, where overhead might be cheaper. This makes even more sense when you consider Philadelphia’s regional transportation system, which is reasonably reliable and arguably one of the better in the country. (Don’t laugh, Philadelphians, I’m serious. SEPTA’s commuter transit infrastructure is nothing to scoff at when compared to other U.S. metro areas.)

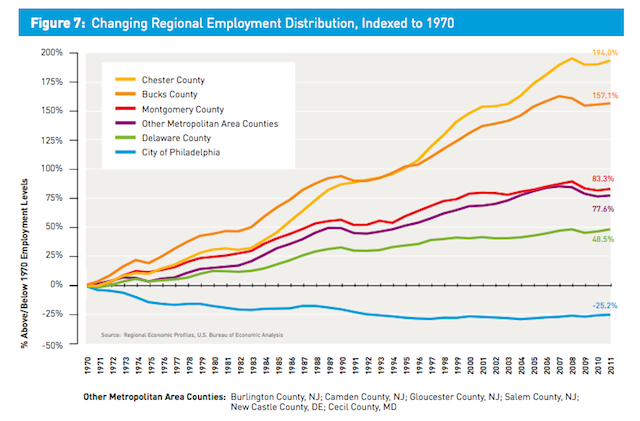

As shown in the graph below, the regional distribution of employment in the Philadelphia metro area has moved everywhere but Philly proper. “Since 1970, every county in the region added jobs to its 1970 base except for Philadelphia, which has 25% fewer jobs than it had in 1970,” the researchers write. In 1970, the City of Philadelphia had 43.3 percent of the region’s job share. In 2011, it accounted for just more than half of that, at 22.9 percent.

Now, it’s worth noting that all U.S. cities lost regional job share from 1970 until the turn of the century (see: deindustrialization, cheaper labor offshore). Philadelphia is not alone in that regard. But while other cities — think New York, Boston and D.C. — lost jobs between 1997 and 2000, things started to look up in the late 1990s. Sure, they lost a huge share of regional employment, but they saw suburban jobs grow in addition to city jobs.

More from the study:

Philadelphia not only has lost regional market share, it also has 25.2% fewer public- and private-sector jobs within its boundaries than it did in 1970.

These peer cities have simply done a better job creating post-industrial replacement jobs, offering significantly more urban employment opportunities than they did in 1970. By contrast, Philadelphia has 232,551 fewer (-28.6 percent) private wage and salary jobs than it had in 1970 and 34.4% fewer (-57,283) government positions than 40 years ago, for a cumulative decline of 25.2 percent.

There’s no quick fix, but in the meantime Philadelphia could help turn the tide by taxing the land instead of the businesses. The study offers some promising projections for what higher property taxes could mean for the city’s tax base:

For example, increasing average Class A rents downtown $1 per square foot — from $27 to $28 per square foot— would yield $8.2 million more each year in real estate taxes just from the central business district. If rents rose to Cira Centre or Chicago levels — $37 per square foot — that would provide $87.5 million more each year in real estate taxes, more than half of which would go to the School District. As small businesses make use of vacant or underperforming space across the city, more centers of employment will emerge throughout Philadelphia.

For you non-Philadelphians out there, that mention of the schools refers to a bankrupt district that closed no fewer than 24 schools this year.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.