When Nancy Scola set out to write about Code for America earlier this year, the civic tech non-profit was in the midst of a major change. Its founder, Jennifer Pahlka, had been chosen to serve a year as a deputy chief technology officer for government innovation at the White House. Meanwhile, the organization itself still hadn’t fully settled on a mission: Should it focus its efforts on building useful apps for cities, or should it shoot for something bigger — a “culture change” wherein civic tech becomes a centerpiece of local government, with Code for America leading the way?

Scola addresses these questions and more in her story, “Beyond Code in the Tomorrow City,” which ran this week in Forefront. In the interview below, Scola further elaborates on where Pahlka and her organization are headed.

Next City: Jennifer Pahlka seemed to arrive at the center of the civic tech movement by accident. Do you think a Silicon Valley insider could have followed a similar path to found an organization like Code for America? Or was there a need for an outsider who wasn’t caught up in the private sector culture out there?

Nancy Scola: I do indeed write in the piece that Pahlka’s path was somewhat accidental; she was busy organizing tech conferences in the 2000s and, though she recognized that the software Silicon Valley was churning out was literally world-changing, grew disenchanted with the industry. She also happened to have a close friend who was a city official in Arizona. But the thing is, she’s followed a course that so many people in the technology world have in the last handful of years. Once you gain a mastery over technology, you start to look to see where else your skills can be applied. And you look to government. That’s Pahlka’s story, for sure, but I think it’s also the tech world’s story.

In the mid-aughts in particular, a few things happened all at once. Washington started paying more attention to the tech world. Washington recognizes power, and Silicon Valley suddenly had a great deal of it. The tech world slowly, then quickly, decided that it should pay attention back. Often it didn’t like what it saw: Government was inefficient, kludgy and where were the data? Also, the people who had launched scrappy start-ups matured and found that they had an interest in putting their talents to work in their offline communities, where they were buying homes, sending kids to school and so on. All of which is to say that there’s been an arc where the tech world has gotten more deeply involved in the civic sphere.

Pahlka is part of that, but so are plenty of others we’d consider hard-core Silicon Valley types. One of the programmers I talked to for this story told me that what Pahlka does exceptionally well is organize people. She organized major conferences, and now she’s arguably the lead organizer of the flowering civic tech movement. It’s interesting to think about what a Code for America started by, say, an engineer would look like, but that’s not the Code for America we’ve got.

Jennifer Pahlka. Credit: Alex Dunne on Flickr

NC: One idea discussed in your story is that certain cities could use CfA fellows because they lack a significant local talent pool of techies. Given how massive the tech industry has become, do you think this is the case? Would Tucson really struggle to find developers to come build an app for the city?

Scola: City officials insist that they do struggle with it. I asked Amanda Deaton, an administrator in Macon, Ga., why she didn’t hire local, and she responded, “If I could do that, I would.” One important thing to keep in mind is that we’re not talking about just any old software developer here. The work Code for America does requires an entrepreneurial software developer. That sort of person can be difficult to find, let alone entice into government service.

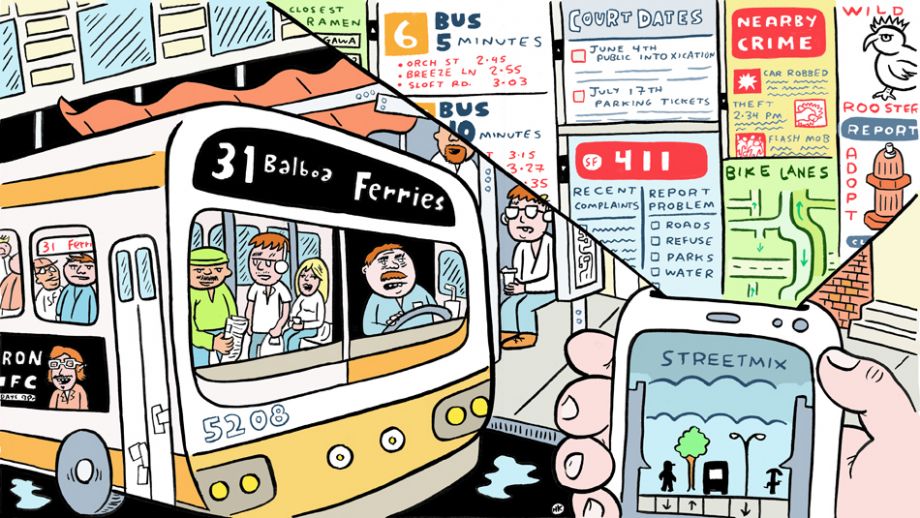

Though that might not always be the case. Companies like Google are investing in civic tech start-ups. They help fund Code for America’s Incubator and Accelerator. The former helps grow Code projects into viable businesses, and the latter fosters existing but still-small civic tech companies. To funders like that, an app that works only in Macon (population: 92,000) isn’t exciting. What’s exciting is an app prototyped and tested in Macon that can be used in other cities. So I think we might get to a time where you don’t need developers to spend a month on the ground getting to know the ins and outs of local government. Plug-and-play only goes so far, but I suspect that such an intense focus on handcrafted, city-by-city civic software will diminish. And that the state of civic tech will mature such that people can be more successful working remotely.

NC: A New Orleans official quoted in the story praised the work of the CfA team that visited his city, but expressed frustration with the options that followed its departure. In your view, how could cities that aren’t steeped in tech maintain the sought-after “culture change” after the fellows pack up and leave? Who builds future apps after the talent returns to the Bay Area?

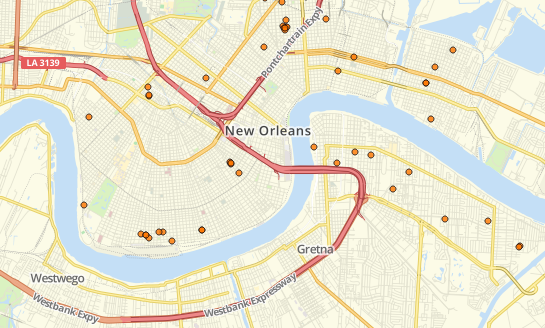

Scola: Yup. That New Orleans official, C.I.O. Allen Square, was a bit upset about his options, which is a perfect way of putting it. He was thrilled with his Code for America experience, mostly. New Orleans has a terrible blight problem, and the app the team built, called BlightStatus, helped the city address it seriously for the first time in a long while. Square even, he said, tried to convince most of the fellows to stay on in the city and work for him. But it’s a matter of having a taste of something good and wanting more of it. Sustainability is a huge question in civic tech. Just earlier today I came across someone in the non-profit world complaining that geeks come in and install their favorite content management system, and then locals have a tough time keeping it up when they leave. Code for America is probably going to have to spend more time figuring out “what’s next” for cities after.

There are a handful of post-Code options for city administrators. Find the money and political will to hire developers on full time. Work with outside contractors, newly equipped with the knowledge of what you want from technology. Find people already on the city payroll who might be up to helping out. Learn enough about software coding and design to do it yourself. Try to wrangle more support from the civic tech community. I’m putting it on my calendar to do a follow-up in five years to check in on Code for America’s projects. Their afterlife is going to be fascinating to track.

Also, to your question, it’s probably worth noting that not all the fellows are from the Bay Area, though plenty are.

Screenshot of the BlightStatus app.

NC: At the time of your writing, teams of fellows in both New York and Louisville were struggling with apps that would deal with crime data in both of those cities. It was a greater challenge than CfA had dealt with in the past, and both teams had hit roadblocks. If they succeed, what would that mean for CfA and the direction it wants to take? Likewise, what would if mean if they fail?

Scola: In researching and writing this piece, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out whether the sort of projects you mention — which have to do with upgrading how city criminal justice systems handle information — are tangential to the work that Code for America does or central to it. I came away thinking that they’re central to it. Many of the people around Code for America will concede that if all that ever comes of their work is building a better bus app, they’ll have fallen short of their promise. But doing more means confronting the essential nature of government, which is resistant to change.

The nice thing for the fellows is that they’ve got one foot in a world where failure is an option. [O’Reilly Media founder and CfA emeritus board member] Tim O’Reilly explained it to me as, “you don’t expect the first start-up in a space to win.” The tech industry is such that it has spawned events like FailCon, and among entrepreneurs there’s even an eagerness to talk about what they’ve botched along the way, as long as they’ve learned something from it. Google, for example, has an internal rating system where you’re only supposed to achieve a 0.7, out of a scale of zero to one, of what you set out to do each quarter. Doing better than that suggests that you aimed too low to begin with.

In government, meanwhile, failure has tended to be embarrassing, something to be explained away. But Code for America succeeds, I think, as long as their city partners think that they’re getting something out of it. And city officials I spoke with said that for now, at least, learning a new way of doing things is enough. So as I see it, those projects are kind of win-win. They’re moon shots, useful if for nothing else then for stretching the imagination. Besides, as one of the city officials I interviewed said, “the dollar amount is at the level where there’s not a heavy level of scrutiny.” It’s an app, not a lunar module.

NC: Even though the organization is only four years old, it’s hard to imagine Code for America without Pahlka at the helm. Now that she’s off to the White House for a year, what do you think will happen with CfA? Will it continue developing its role as a missionary group for civic tech, or will it take a more meat-and-potatoes approach to building apps that serve cities?

Scola: It’s going to be interesting to see how this year unfolds because, yes, the organization is imbued with Pahlka’s spirit. It’s being led, while she’s gone, by Bob Sofman, the program director, and chief of staff Abhi Nemani. Both have been intimately involved in leading the organization for a good chunk of its life. I don’t know how much the organization’s direction will change in 12 months; planning was already well advanced when Pahlka left, and she told me that they were already thinking about how they want to tackle the 2015 fellowship year.

One thing to keep in mind is that in many ways the point of the current iteration of Code for America is to figure out how to leave behind the Code for America way of doing things even once the fellows are gone, so that innovation can keep chugging along without them. As Pahlka said, a marker of success they look for is that “the institution is different, not just the people.” If Code can’t manage without Pahlka, that might suggest that the approach needs work. What I’m actually especially curious about is what happens when Pahlka gets back from spending a year in the White House. What does Code for America look like when it’s run by someone who’s lived through Washington?