Following up on my review of Moses Gates’ Hidden Cities, Next City enlisted Bradley Garrett, a researcher at the University of Oxford who studies urban exploration or “place hacking,” to talk about Gates’ book, how the notion of public and private space differs depending on where you are, and why seeing an empty train tunnel is worth the risk.

Garrett’s own forthcoming book, Explore Everything, will continue the story of urban adventuring, beginning around the time that Gates’ adventures began to taper off and continuing into the current decade. Explore Everything will come out in October of this year.

Next City: So you’re an urbexer, too, like Hidden Cities’ author Moses Gates. Give us a couple examples of some of your place hacking greatest hits.

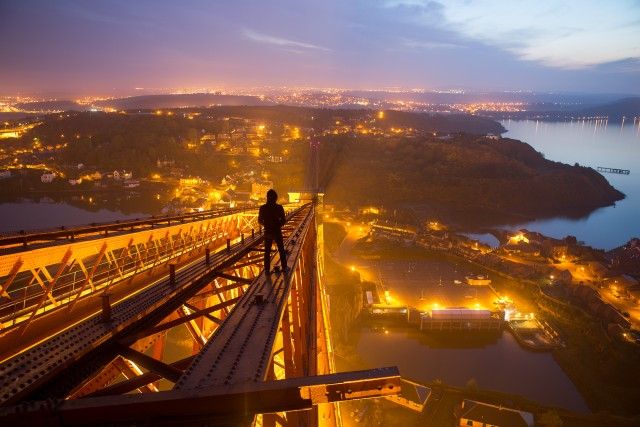

Bradley Garrett: Yeah, Moses and I have been exploring together for a few years, though we’re separated by geography. I think I met him in a sewer. I’m pretty sure we were in a sewer. Maybe in Antwerp? But last year we climbed the Forth Rail Bridge in Scotland together, the entire thing from North to South, and that’s when I felt like I really got to know him. Exploring is good for that. Once you’ve almost died together, you can definitely call someone a friend.

I have spent the past four years exploring mostly in London. Over here, we’ve climbed most of the major construction projects, including The Shard, the highest building in the EU, and seen all the abandoned Tube stations and some really deep infrastructure like the Kingsway Telephone Exchange, where the first transatlantic phone cable terminated. We’ve also climbed the chimneys of Battersea Power Station, the one that was on the cover of a Pink Floyd album. [Animals, if anyone is wondering. –Ed.]

NC: One of the things Gates said was how he can’t identify with people who just know a little of a city. For example, if they only know their neighborhood, or maybe a couple parts of town. But I couldn’t help but ask myself: When you take that a step further, and folks start going beyond the “No Trespassing” signs, wouldn’t it be a giant mess if everyone were doing it? If everyone ignored the “Do Not Enter” signs, wouldn’t it get to be a huge problem?

Garrett: There are plenty of places in the world where “No Trespassing” signs don’t exist, and many others where those signs are more of a suggestion than a command. I think one of the things that Moe’s book does beautifully is that it gives you a sense that rules, laws and social expectations vary depending on where you are in the world.

NC: The chapter about the Paris police was amazing to me. It was one of those parts of the book that made me realize that I was just a different kind of guy than Moses and his friends. I could maybe see myself climbing some scaffolding, but, if I got stopped by the cops and they let me go, I would not go for a “victory lap” and climb something else. I would go to bed.

Garrett: Getting caught in Paris has smaller consequences. The French appreciate eccentricity and creativity and that extends even to the police. The tradeoff is slightly less “security,” but we obviously think that’s a good trade off.

The Western capitalist world is dominated by two huge controlling factors — money and fear. The reason those signs are usually there is to protect the wealth of insurance companies and corporations, not us. That’s a great reason to ignore them and get over the fear they try to instill in us to keep us complacent.

NC: Well that leads into the underlying theme of the book that seems to me to be really important to urbanists. Gates describes the various public observation decks that used to exist around Brooklyn, for example. There were a lot. Now there are few. Do you think that on some level developers and property owners and the government has a responsibility to give the public more access to great spaces? Great views?

Garrett: Most urban explorers don’t push for preservation because obviously when you “preserve” something under a heritage regime, you lose a lot as well. Look at the High Line in New York. It used to be an amazing place when it was derelict. Now it’s ruined, in my perspective — too controlled, too sanitized. It’s often much better for the powers-that-be to simply stop spending money, turn a blind eye and let people do their thing. Then people build a sense of community and place on their own terms.

NC: Only the folks who are willing to cross those lines, though, right? It’s not really public access since most people just won’t cross over those thresholds. A lot of people will, but not most. I definitely agreed that, at least in the States, we are way too careful and conservative about what spaces are accessible and what aren’t.

What I was looking for as I read this book was a way to think about how more great spaces could get more access to the public, and cities could be made more interesting and exciting places to be, knowing that most people are probably going to abide by the rules.

Garrett: Well, the reason most people don’t cross them is because they’re told not to. Generally, people are pretty good about following instructions. Until they see someone else cross a line and realize they can, too. In Germany, I’ve seen families pushing prams around abandoned hospitals and industrial site, having picnics. They don’t have the same mental lines drawn.

The thing that Moses does really well is that the book isn’t really about urban exploration. It’s about letting yourself be curious. I think the book is much more in the tradition of the flâneur than the urban explorer.

From left to right: Bradley Garrett, Moses Gates and fellow explorer Steve Duncan at the International Drain Meet in Antwerp, Belgium in 2012. Credit: Helen Carlton

NC: So what are some good models for making more interesting spaces accessible? Do you think the book has lessons for policymakers? Urban planners? Developers?

Garrett: Yeah, absolutely. What Gates shows is that there isn’t any one good model for what kind of spaces people need to be happy. People need a range of different types of places on a sliding scale. And that has to be weighed against political, economic and cultural imperatives. So here in the U.K., English Heritage has recently started adopting a policy of allowing places to decay and eventually disappear. That’s awesome. Preserving or redeveloping places shouldn’t always be the only option. Equally, there should be places you can paint and smash up — that kind of playful space is valuable, too.

The problem is, many places really only consider the economic model: If a place isn’t profitable, it needs to be made profitable. That’s a really sick mentality that erodes a locally grounded sense of place.

NextCity: True. It’s like folks here in America who say that we shouldn’t have parks unless people are willing to pay to use them.

In Philadelphia there’s an organization called Hidden City. It finds spaces that are either abandoned or, more often, still in use — but membership only, or otherwise closed to the public — and opens them up for a limited period of time in the summer. They get some team of artists to come into the space and do something interesting in it, as well. So it opens up spaces that were once closed off, but does it in a way that works for folks who own the property.

Garrett: That sounds like a great model. It reminds me of squatting laws in the U.K. where often the property owner is relived to have someone in an empty building caring for it, because at least it has some value. Maybe not economic value, but it’s a win-win.

NC: Are you familiar with Woodstock II in the U.S.?

Garrett: Yeah, I heard about it.

NC: So you know how Woodstock was hippies and happiness and hanging out, right? Then Woodstock II happened 25 years later, and it was a big rowdy chaotic mess. Folks turned out just to raise hell and make trouble. Not the same vibe at all. I just wondered if that kind of thing ever happens with an abandoned space. You get the explorers with a certain ethic, and it’s all right. But then it gets popular and before long folks are showing up who just want to make noise and create chaos. Does that ever happen?

Garrett: Yeah, but look: Moses is really careful not to really define urban exploration too rigidly in his book, and even at one point suggests that making rules for a community of rule breakers is ridiculous. We are very much like the hacker community, whom Acid Phreak said “has no one ethos, every hacker has their own.” I want to explore and experience a space on my terms. That does not then give me a right to tell the next person they can paint it or throw a TV off the roof or whatever it is they want to do. The greatest part of urban exploration is you don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s all about chaos!

NC: On that note, I did spend the whole book trying to get a sense for Gates’ personal ethic. Do you have rules for yourself, when you’re exploring?

Garrett: Yes, I have two rules. The first is that if my heart isn’t racing, I push it more. I call this “edgework” (borrowed from Hunter S. Thompson). Basically, the idea is to get as close as possible to the “edge” without getting cut, or at least not too deeply. The second rule is that I never try to let my edgework negatively impact someone else. So if I encounter someone living on site for instance and my presence is bothering them, I’ll leave.

NC: I really liked the story of the art gallery in the subway. I also liked the story of the party in the train tunnel where Brooklyn lived. On some level, I liked the idea that the cost of entry to a certain kind of experience would be knowing the secret of existence and needing to sneak to get there. Have you been a part of secret cultural events? Underground theater productions or art galleries or movie screenings? Got any favorites that you saw?

Garrett: I’ve seen some incredible stuff in London in “informal” spaces. We’ve even thrown some of our own. We had the World Premiere of Crack the Surface II, which Moses features in, inside London Bridge, totally illegal. We got 80 people in there!

NC: I’ve known some theater types who’ve really struggled to find affordable spaces to perform in. The book made me wonder if using some cafeteria in an abandoned school might not be a pretty good solution for some of them.

Garrett: Punch Drunk and the Old Vic did some participatory theater in the tunnels under Waterloo Station that was really good. Then they shut it down before it got stale, which I appreciated. Also, Secret Cinema in London has always been good fun and takes you somewhere you might not expect. However, that inevitably is getting quite commercial and expensive.

NextCity: This makes me think of a conversation that Next City recently participated in with the New Cities Foundation, via Twitter, in which the moderators asked how can we gamification can be used to make cities more human?

Q5/ How can #games and #gamification help us plan more human #cities? #NCS2013

— NewCitiesFoundation (@newcitiesfound) May 15, 2013

Gates’ book certainly does it make it sound like there is a game already built into every city. “Easter Eggs” all over the place.

Garrett: Life is a game, man. It’s just we’re usually playing by other people’s rules. Urban exploration is about defining the terms of the game for ourselves. It is incredible though how once you cross the boundary, once you begin seeing those Easter eggs, they’re everywhere and you can’t stop it even when you want/need to.

NC: That’s the part I’m still struggling with. I have to be honest. Gates did not convince me of that with this book. I am no more likely now to cross those boundaries than I was before.

Garrett: Because he made it seem difficult?

NC: I just wasn’t convinced that it was worth it. Nothing sounded cool enough even to sit in a squad car for an hour if I got caught. Even if that were the extent of the consequences.

Garrett: Right, that’s about the risk/reward ratio.

NC: So I guess the question for me was, from a planning perspective, how do you open more things up, or relax the rules — or get cops to chill out — in such a way that the edges open up a bit more? So that people can get to more Easter eggs, if that’s what they want to do. And cities can be more exciting, but the risk won’t seem as high.

Garrett: Look, most of us have been arrested. In my case, I was pulled out of a plane on the tarmac at Heathrow. A serious overreaction by the police to me rooting around in the London Tube after hours, but the exchange was that I got to see an abandoned Tube station that contained Winston Churchill’s secret bunker in pristine condition. Maybe 100 people on the planet have seen that station and bunker. Do you really think, in 20 years, you’re going to look back and regret getting into a bit of trouble to experience something like that?

I don’t think what Gates is saying is that everyone should start popping manholes open and climbing into construction sites. We do that, we love it and we are happy to take bigger risks for bigger rewards. But by doing that, and sharing it with people, we hope that it inspires others to engage in the world more creatively on their terms. And maybe to realize they can get away with more than they thought they could if they want to push it a bit.

The beauty of urban exploration isn’t in the places. It’s in the people. Gates’ book relays that really well. The community we’ve built together is a gorgeous collection of global adventurers, all with different backgrounds and motivations — I’ve never seen anything like it. Certainly there’s a lesson there somewhere in the context of many people feeling a sense of disconnectedness in the world.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.