Unlike during much of the 20th century, manufacturing and industry are no longer the major drivers behind Philadelphia’s economy. Meanwhile, Mayor Michael Nutter has implemented the ambitious “Greenworks” plan in an effort to make Philly “the greenest city in America.” But with the recent shale oil boom throughout Pennsylvania, one South Philly refinery could see new life as a vital epicenter of the emerging industry.

In Forefront this week, Next City Fellow and longtime Philadelphia reporter Patrick Kerkstra sets out to see if clean, new 21-st century Philly has room anymore for dirty, old heavy industry.

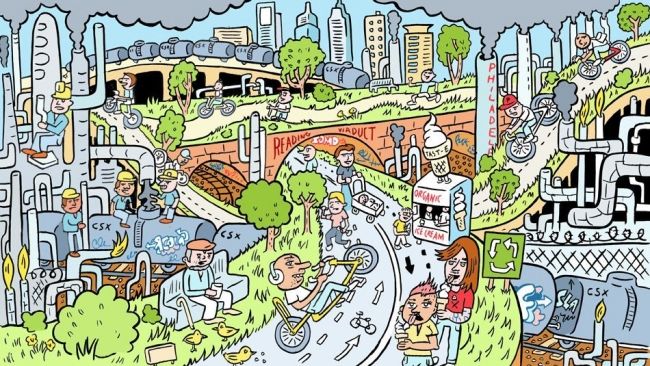

The trip from Philadelphia’s international airport to Center City is a short but fascinating journey through the city’s economic past and into its promising post-industrial future. One of the first scenes greeting visitors is an aging oil refinery, a 1,400-acre behemoth at the southern terminus of the Schuylkill River. The refinery — a vast and byzantine network of pipes and towers — is the very embodiment of industry. Steam billows from countless release points. Flames dance from flare towers high above the facility. Dozens of oil tanks line both banks of the river, sitting round and squat atop barren land that has hosted refining operations since the 1870s.

The scene is borderline dystopian, the kind of image that gives city tourism marketers fits.

But at highway speeds, the tableau passes quickly enough. Just as the refinery moves into the rear-view mirror, the towers of hospitals, universities and research centers appear on the western banks of the Schuylkill, while the brownfields and asphalt yield to waterfront bike lanes on the east. And soon, Center City’s skyline dominates the view. There, beneath those towers, is Philadelphia’s future: A walkable downtown, blessed with outstanding transit connections and handsome architecture, all built on a very human scale. It is an old model of sustainable urban living made new.

Despite what the trip from the airport might suggest, the big business in Philadelphia today isn’t manufacturing, a sector that has been in steady and steep decline since the 1950s. Philadelphia’s contemporary economy is built on higher education, medicine, hospitality and the service industry, just as in so many other big U.S. cities in this post-industrial age.

Indeed, less than a year ago, the sprawling refinery complex was on the verge of shutting down. The homegrown Sunoco oil company had decided to get out of the refining business altogether. By this time last year, it had already idled its Marcus Hook refinery, and there looked to be no viable buyer for the Philly refinery either. A few months earlier, ConocoPhillips had shut down operations at yet another local refinery, in the borough of Trainer. Taken together, these had produced half the gasoline made on the East Coast.

Even so, few were surprised by the developments. Jobs would be lost, which was unfortunate, but the economics of oil refining are difficult, gasoline demand is slipping in the U.S. and, well, perhaps there were better, higher uses for prime waterfront space so near the core of a recovering city. If nothing else, the optimists suggested, the closings might help the city make a better first impression.

But then something altogether unexpected happened. The refineries didn’t close. New owners acquired two of the sites, and a third is being converted into a holding and (in time) processing facility for natural gas from Pennsylvania’s vast Marcellus Shale fields. Keeping the facilities open took some political acrobatics and an uncommonly impressive display of public and private sector cooperation. But none of that would have been sufficient were it not for a dawning recognition of just how massive Pennsylvania’s shale gas boom actually is, and what it could mean not just for the gas fields far to Philadelphia’s north and west, but for the city itself.

“We’re not rescuing anything,” said Philip L. Rinaldi, CEO of Philadelphia Energy Solutions, the new entity formed to purchase and run the South Philadelphia refinery, when the acquisition was announced last year. “We’re coming in here to build industries.”

This doesn’t look like empty CEO bluster. All of a sudden, the national fracking boom has arrived in Philadelphia, and its impact on the city could be profound.

With tax breaks and public support, Philadelphia Energy Solutions is building a high-speed rail unloader (with the help of a big taxpayer funded grant), the better to offload oil from trains that have rumbled all the way to Philadelphia from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota. Sunoco Logistics, meanwhile, is already modifying a pipeline that runs from the gas fields in the west of the state to Marcus Hook, the old refinery site 17 miles south of Philadelphia. Once finished, that project would give all Philadelphia area facilities — already connected by pipeline and rail to Marcus Hook — direct access to the Marcellus Shale.

Remarkable as it may seem, a growing number of business and government leaders now contend that the Philadelphia region has the potential to become a major national energy hub: Refining oil, processing shale gas and providing feed stock for petrochemical companies.

“Pennsylvania sits on top of the second largest shale gas formation to the world. Linking that field to facilities in Southeastern Pennsylvania — the refineries, the port — I liken it to the golden spike at Promontory Point,” said Michael Krancer, the former secretary of Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection and an ardent supporter of fracking. “It’s that dramatic an opportunity.”

Overwrought though Krancer’s metaphor may be, the analogy works. The linking of Western Pennsylvania’s resources to the markets and manufacturing capacity of the eastern seaboard is a significant economic development.

But the opportunity is a complicated one for a city that has spent decades trying to turn the page on its industrial past, not because manufacturing was unwelcome, but because it seemed so clear that industrial jobs were never coming back. Not in large numbers, anyway.

That assumption — built on 60 years of folding factories and outward migration — may actually be proven wrong by the shale boom. The question is, would that actually be a good thing for Philadelphia?

To read more, subscribe to Forefront. Already a subscriber? Click here to continue reading.