It’s old news by now that people and businesses have moved back to urban downtowns. Last year, a Census Bureau report on the country’s population trends proved as much, though we can’t read the report right now because our government is closed and its websites are down.

The problem with this data — though it verified many trend stories about the resurgence of downtowns — was how it actually defined “downtown.” The criteria was simple and rudimentary: Anything within a two-mile radius from City Hall. Which any city resident, from Philadelphia to Detroit, will tell you is wildly imprecise. (Not to mention that a two-mile radius often includes waterways where no people live or work.)

But a report by Philadelphia’s Center City District for the International Downtown Association is trying to set new parameters for defining what downtown means, so we can better keep track of job numbers and residents. The authors use the Local Employment Dynamics (LED) dataset from the Census Bureau to create heat maps of job density (though they still include the occasional river). The data also shows where employees live and work, so researchers can see how many folks actually stay downtown after work hours.

The study examined 231 major employment centers in the country’s 150 biggest cities, and for the first time figured out exactly how many jobs are in the downtowns and anchor institution districts. All told, these areas contain 14.4 percent of American jobs.

As you might assume, most cities don’t have one singular downtown employment center. Manhattan, which has office buildings from Wall Street to Central Park West, is an easy example here. But let’s look at Detroit’s numbers, where Dan Gilbert owns 30 buildings and moved his 9,200 Rock Venture employees downtown from dreary suburban office parks. There’s the downtown core and central business district (where many of Gilbert’s buildings are) and Midtown, what the report calls a “Secondary Employment Node.”

There were 78,144 jobs downtown and 72,911 in Midtown. If the report had used the old-fashioned two-mile radius map — which might have stretched all the way across the Detroit River to Canada — there’s no telling how many of the jobs in Midtown wouldn’t be counted.

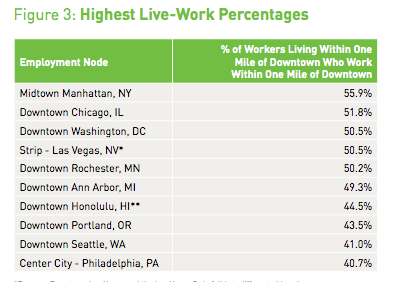

Redefining what constitutes downtown is hugely important, but I’m most interested in the live-work dynamic. The numbers provided here are intriguing — Midtown Manhattan, Downtown Chicago and Downtown Washington, D.C. have the highest-live work percentages — but I’d like to see the researchers expand on that. Transit is arguably the single most important thing when we’re talking about fully functional cities, and a robust transit system means you don’t have to live in the central business district, which is a generally unpleasant place to live anyway.

Here, the authors define live-work as the percentage of workers who live and work within one mile of downtown. You certainly don’t have to live one mile from downtown to feel like you live in a city or are part of whatever vibrant downtown there might be. It seems strangely limited.

“Contrast a 50-minute commute by car with a 15-minute walk to work,” the authors write. I worked in midtown Manhattan for five years with a 35-50-minute subway commute from Brooklyn, and I certainly felt like I was part of the city. I’d even argue that in transit-rich cities, where the downtown is easily in reach by a short bus or train ride, fewer people want to live in the center of downtown.

The parameters that the report’s authors have determined for downtown are hugely helpful, as a more accurate understanding of job density can improve the quality of development and urban planning in our cities. But perhaps now the challenge is changing the definition of live-work. One mile is an awfully small area, even in dense cities. We need to concentrate on job density and those employees that live in the city proper, not job density and employees who walk to work. They’re in the minority.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.