This piece originally appeared on The Transport Politic.

(I) The Accomplishment

The U.S. Senate’s passage of a transportation reauthorization bill Wednesday was big news, if only because it has now been 898 days since the last transportation bill officially expired. Three years of debates in both houses of the Congress have brought us one proposal after another, but only one piece of legislation has actually made it out the doors of one of the chambers. That is a serious accomplishment for Barbara Boxer’s leadership in the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

Senate Bill 1813, also known as MAP-21 (“Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century“), is a $109 billion law that will remain in effect for 18 months if passed by the House. It reorganizes several national transportation programs and includes a number of interesting features, some of which I describe later in this piece.

Of course, the specific policy measures of MAP-21 may be meaningless despite the bill’s 74-22 passage margin, which included about half of the GOP contingent in the Senate; House Republicans have suggested that they have little interest in moving forward with this bipartisan legislation. Current funding for transportation runs out on March 31; at that point, if nothing happens at the Capitol, collection of fuel taxes and distribution of transportation funding from Washington to the states will cease. What seems most likely is yet another extension of the existing transportation bill, originally passed in 2005 but now woefully out-of-date and underfunded.

Some have noted that MAP-21, for all the acclaim it has received (at this point, any bill to get through would likely be lauded…), is ultimately little more than another extension of the existing law. But, as Lisa Schweiter has written, it does nothing to resolve the financing difficulties that plague America’s transportation funding situation. The bill will require a significant infusion of money ($12 billion) from sources other than the Highway Trust Fund. In other words, it will not be fully funded through the fuel tax user fee, which many would like to see increased to cut down on automobile-produced externalities and force a link between spending on transportation infrastructure and revenues derived from transportation. It is unclear how the next bill, facing even fewer revenues from the Trust Fund, would be funded.

Yet the political conditions in which MAP-21 did pass are indicative of the bill’s importance. We are, after all, in a tightly contested election year in which Republicans have set their sights on the White House and Senate as Democrats eye the House. The bipartisan passage of the legislation — though not as close to unanimity as many previous transportation bills — suggests that there continues to be relative consensus among both parties that there is a rationale for federal investment in transportation infrastructure. Republicans in the Senate could have easily deflected the bill’s passage, forcing yet another extension — but they chose to cooperate and produce a less-than-ideal bill that will nonetheless keep people employed and America’s infrastructure in reasonable condition.

It is true that the Highway Trust Fund’s diminishing pot of funds — caused by the coinciding effects of an overall decrease in driving, better fuel efficiency and the lack of any inflation adjustments on the levy since 1993 – imperils the future of U.S. transportation funding, whether or not MAP-21 makes it to President Obama’s desk. But Congress is not run by economists. It is run by politicians who, for better or worse, must respond to the demands of their constituencies.

What is unquestionable is that the level of support for a national increase in the fuel tax is minimal. Republicans are hammering the administration for presiding over a significant increase in fuel costs since 2009, despite no increase in the tax. Meanwhile, Democrats are legitimately worried about increasing the burden of transportation costs on the nation’s lower- and middle-income households. In discussing how to pay for transportation, we cannot forget the fact that a majority of the nation’s poor now live in suburbia — most of them far away from the nation’s underdeveloped public transportation system. Increasing the gas price will do significant damage to the purchasing power of tens of millions of Americans in the short and medium term. There’s a reason that doing so has little political momentum.

Transportation experts may not like the sound of it, but funding for national infrastructure is not — and likely will not be — fully user funded (it wasn’t even when the Highway Trust Fund was on more solid fiscal ground). In fact, its role is as somewhat of a redistributive tool, encouraging mobility by subsidizing cheaper travel both through cheap roads and, in the cities, transit. Helping people to get around is a bipartisan policy goal. This leaves MAP-21 in the uncomfortable position of relying on outlays from federal funding sources other than the gas tax. In this day and age, that comes in the form of debt.

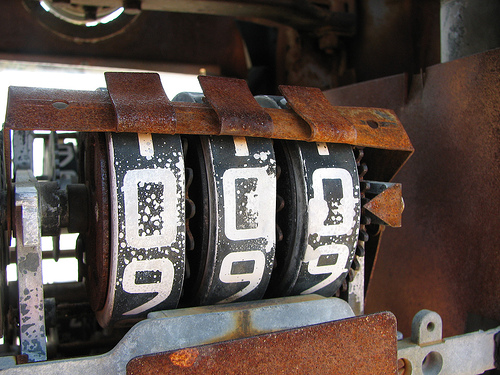

Credit: Gregory Bleakmore on Flickr

(II) The Policy

Despite the limited nature of the MAP-21 legislation, there were nonetheless some significant changes to federal transportation law contained within. Most intriguingly, the bill puts into question the future of private sector involvement in the transportation field.

What MAP-21 does not do is either cut funding for sustainable transportation dramatically (as would have the still-born House Republican proposal, H.R. 7) or devolve transportation funding and decision-making entirely to the states, a revision whose primary consequence would be putting more highway-crazed state Departments of Transportation in charge. It was, in other words, not a good policy. Thankfully, two amendments to MAP-21 that would have done so failed by huge margins in the Senate — Senator Jim DeMint (R-SC)’s by 30-67; Senator Rob Portmans (R-OH)’s by 30-68—suggesting that there is little support on either side of the aisle for moving all transportation policy to the states.

MAP-21 is designed to provide a framework for a significant reworking of the nation’s transportation policy structure. It does so first by establishing a set of national goals for the mobility system — to improve the freight network, to ensure a state of good repair for existing infrastructure and to reduce congestion, for instance. These largely symbolic efforts may come to play a larger role if MAP-21 enters into the law and is eventually expanded by future legislation.

More importantly, this bill consolidates duplicative programs in the Department of Transportation and at least in theory streamlines project delivery processes to ensure faster construction timelines and cheaper costs. Whether these changes will actually improve the construction and operation of transportation in the U.S. remains to be seen.

Though MAP-21′s investment strategy is generally designed to continue existing levels of federal transportation investment (at an inflation-adjusted pace) including the now-standard 20 percent of funds for transit, it includes several measures that are beneficial to sustainable transportation options. For one, the TIFIA program, which offers federal loan support and can back significant private investment in new infrastructure, would be expanded from $122 million a year to $1 billion a year. For cities like Los Angeles, which wants to expand its transit network at a breakneck speed, this could be a huge boost, as it allows cities to take out more loans at lower, federally backed rates.

The bill permanently equalizes commuter tax benefits for transit commuters with those received by people who park, a long sought-after rule. It also allows transit agencies to use federal funds to pay for operations costs in certain situations. This is currently not to be covered using money from Washington (because transit funding is currently reserved for capital expenses). This is a huge advance that could provide downtrodden metropolitan areas the ability to maintain services on their bus and rail lines even when they face declines in revenues from other sources, which has happened in most U.S. cities since the beginning of the economic crisis.

Despite the inclusion of more money for TIFIA, the bill’s stance on private involvement in transportation is mildly contradictory. The House bill H.R. 7 would have given transit agencies a monetary incentive for contracting out their services to private operators. This was, to be frank, a giveaway to the private transportation industry. MAP-21 has no such provisions.

On the other hand, MAP-21 includes an amendment proposed by Senator Jeff Bingaman (D-NM) that passed 50-47 that excludes private highways from the calculation of a state’s guaranteed transportation funding through standard federal formulas. Currently, states are provided highway funds in part based on their mileage of federal highways; the Senator’s amendment simply says that roads that used to be public and were transferred to a private entity should not be counted in that calculation. Bingaman argued that “drivers across the nation shouldn’t be subsidizing any state that has chosen essentially to “sell off” an existing highway to the highest bidder.” He has a point, and his amendment seems likely to dissuade states from continuing down this particular path, but it does seem to be somewhat of a contradictory move on the part of the Senate: Does it want private investment through programs like TIFIA, or not?

Altogether, the Senate’s proposal is a significant advance over the existing law. If it were passed by the House, American cities would benefit.

Nevertheless, MAP-21′s ultimate failure remains the fact that it fails to provide for a significant expansion in funding for sustainable infrastructure projects. President Obama, whose administration continues to officially promote the passage of a bill that would double national transportation spending and devote a far higher percentage of it to transit, livable communities and high-speed rail, has been shunned to the sidelines in the Senate debate. And the nation’s mobility systems will suffer as a result.

What, then, can we make of the future of the nation’s transportation network? What is inevitable is that MAP-21′s success or failure in the House of Representatives will do nothing to resolve the legislative confusion between the oft-repeated claim that transportation should be paid for through user fees and the embarrassing fact that there aren’t enough user fees being collected to pay for the things we want.

Yonah Freemark is a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where he is the research director of the Land Use Lab at Urban. His research focuses on the intersection of land use, affordable housing, transportation, and governance.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)